Apollo 11 50th Anniversary

by Martin Rees, author of On the Future: Prospects for Humanity.

The first steps away from our Earthly home are epochal events in the history of our planet — so it’s right that we should remember and celebrate the Apollo astronauts.

Overview

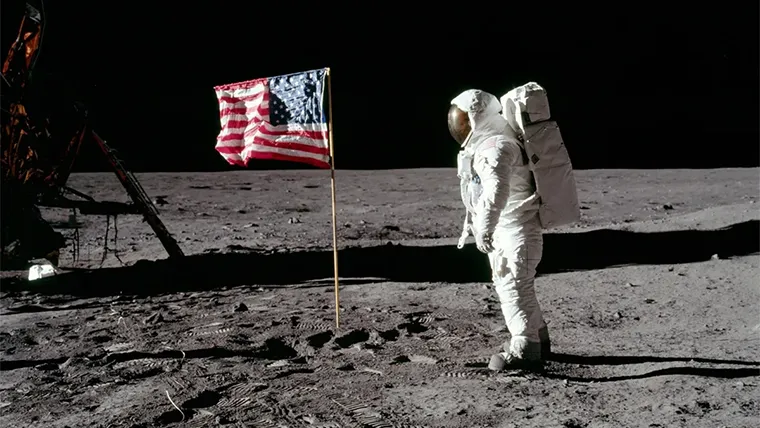

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot of the first lunar landing mission, poses for a photograph beside the deployed United States flag during an Apollo 11 Extravehicular Activity (EVA) on the lunar surface.

I never look at the Moon without being reminded of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — and of the day, 20 July 1969, when they left their first footprints on its dusty surface. Along with hundreds of millions around the world, I watched the grainy TV images of this historic moment. I was then a young astronomer in Cambridge, where Fred Hoyle was the top professor. When I met Fred the next day, he was specially enthralled. He wrote science fiction as well as doing brilliant science: he’d been anticipating this moment since his own childhood in the 1920s.

The Journey Begins

The exploit seems even more heroic in retrospect, when we realize how ‘primitive’ the technology was, NASA’s entire suite of computers was less powerful that a single smartphone today. And crucial equipment was untested — especially the Lunar Module that was supposed to blast the astronauts off the Moon’s surface for the return journey. President Nixon’s speechwriter William Safire had drafted a speech to be given if a malfunction left them stranded:

“Fate has ordained that the men who went to the Moon to explore in peace will stay on the Moon to rest in peace. [They] know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice”.

In 1957 the USSR launched ‘Sputnik 1’, the first object ever to go into orbit around the Earth. This was followed by a capsule carrying a dog called Laika; and then, four years later, by Yuri Gagarin’s orbital flight.

(When Gagarin visited London on a triumphal tour he was mobbed by enthusiastic crowds — though Harold MacMillan, prime minister at that time, sardonically remarked that it would have been ‘twice as bad if they’d send the dog’!)

These Soviet successes — a correlate, of course, of Russian prowess in developing intercontinental ballistic missiles — caused alarm in the USA. It was with the aim of catching up, and establishing US pre-eminence on the ‘high frontier’ of space, that in 1961 President Kennedy declared:

“...I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space.”

John F. Kennedy announcing in 1961 the goal of landing on the Moon by the end of the decade.

The resultant Apollo programme unleashed huge technological advances, and absorbed around 4 percent of the US federal budget.

Disaster

The first test-flight, Apollo 1, in 1967, was a disaster. The spacecraft caught fire on the launch-pad, killing its three astronauts. But NASA achieved world-wide acclaim at Christmas 1968, when Apollo 8 circled the Moon ten times before returning to Earth. During these orbits the astronauts read from the Book of Genesis and sent Christmas messages to those on the ‘good Earth’. And Ed Anders took the famous ‘Earthrise’ photo — depicting our Earth, with its continents, clouds and blue oceans, contrasting with the sterile moonscape in the foreground. This image has ever since been iconic for environmentalists.

Apollo 8 was followed by two later flights, to test the lunar lander — a small module, detachable from the main spacecraft (which stayed, piloted by a third astronaut, in orbit around the Moon) to deliver two astronauts to the lunar surface.

7 Missions

And then came Apollo 11: the triumphant message ‘The Eagle has landed’, followed by Neil Armstrong’s ‘one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind’.

There were six more missions. All succeeded, except for Apollo 13, where the famous words ‘Houston, we’ve had a problem’ told ‘mission control’ that the power supply had failed; heroic repairs and improvisation by Jim Lovell and his fellow astronauts allowed a safe return to Earth (as portrayed in a memorable 1995 film starring Tom Hanks) Later missions carried a motorized ‘buggy’ on which the astronauts could travel several miles on the lunar surface, gathering samples of rocks and soil.

The Apollo programme ended in 1972, when Apollo 17 returned to Earth.

The first lunar landing was 50 years after Alcock and Brown’s first transatlantic flight (and only 12 years after the first Sputnik). Had the pace of advance in aerospace been sustained in the subsequent half-century, there would surely have been footprints on Mars by now.

But of course this hasn’t happened. The reason, of course, is that Apollo was motivated — and given gargantuan funding — because of the US strategic imperative to ‘beat the Russians’. Once primacy was achieved, continuation wasn’t justifiable. Whenever there’s no economic or political demand, the pace of change is far slower than could be technically achieved. Civil aviation exemplifies this too. The Boeing 747 and Concorde airliners first flew in 1969: we still fly in similar jumbos; and Concorde went the way of the dinosaurs. In contrast, smartphones have advanced and spread globally far faster than management gurus predicted. It’s naïve to think that technological change always accelerates; it sometimes stagnates.

Hundreds more people have ventured into space in the ensuing decades — but, anticlimactically, they have done no more than circle the Earth in low orbit mostly in the International Space Station (ISS). These voyages aren’t inspiring in the way that the pioneering Russian and US space exploits were. The ISS only makes the front page when something goes wrong (when the loo fails, for instance, or when astronauts perform ‘stunts’, such as the Canadian Chris Hadfield’s guitar-playing and singing.)

Space technology has nonetheless burgeoned. We depend routinely on orbiting satellites for communication, satnav, environmental monitoring, surveillance, and weather forecasting.

Unmanned Probes

Unmanned probes have journeyed to all the planets of the solar system. NASA’s New Horizons beamed back close-ups of Pluto, more than 20,000 times further away than the Moon. The Cassini probe spent thirteen years studying Saturn and its moons; more than twenty years elapsed between its launch and its final plunge into Saturn in late 2017. It was therefore designed with 1990s technology. One has only to think of how smartphones have improved since then to realize how much better we could do now.

New Horizons lead by our Alan Stern, visited Pluto which was 20,000 times further away than the Moon.

In coming decades, the entire solar system — planets, moons, and asteroids — will be explored by fleets of tiny automated probes, interacting with each other like a flock of birds. Giant robotic fabricators will construct, in space, solar energy collectors, telescopes, and other giant structures. Indeed some (like 2018 Lifeboat Guardian Award winner Jeff Bezos) envisage that much industrial production could eventually happen away from the Earth.

But will there be a role for humans? There’s no denying that NASA’s recently-landed InSight, trundling across the Martian surface, may miss startling discoveries that no human geologist could overlook. But machine learning is advancing fast, as is sensor technology. In contrast, a huge cost gap remains between manned and unmanned missions. The practical case for manned spaceflight gets ever weaker with each advance in robots and miniaturization.

To today’s young people, the Apollo programme is ancient history — all over long before they were born. Of the 12 men who walked on the Moon only 4 are still living. I recall hearing a rather crass enquirer asking Harrison Schmitt what was most special about his 3-days on the Moon during the Apollo 17 mission. He just replied ‘Being there’. Will there be a time when no human has first-hand memory of standing on another world? Along with millions of others, I’d be saddened if human exploration of space faded into history.

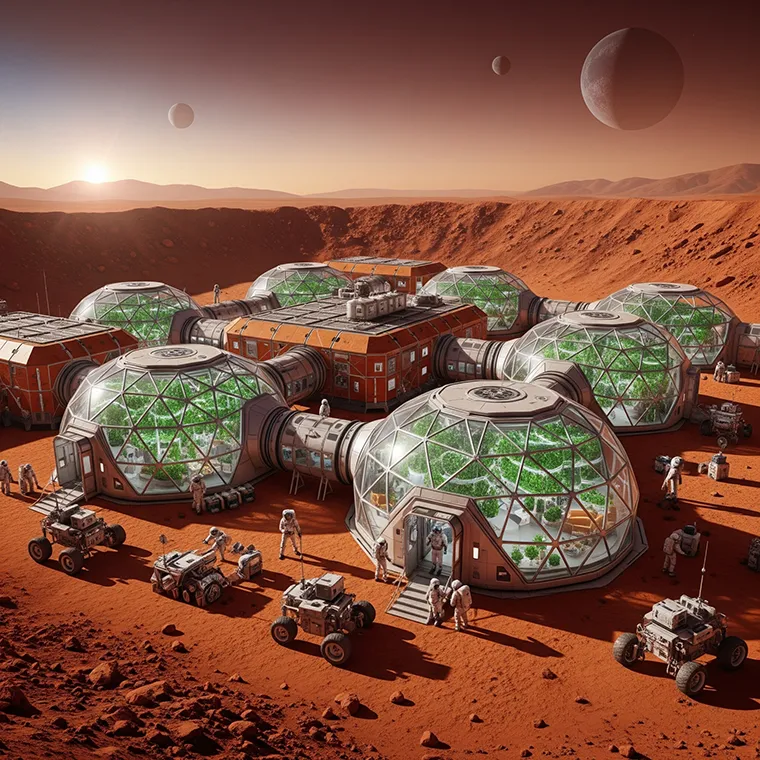

If there were a revival of the ‘Apollo spirit’ and a renewed urge to build on its legacy, a permanently manned lunar base would be a credible next step. It could be constructed, before humans went to it, by robots bringing supplies from Earth and mining some from the Moon. An especially propitious site is the Shackleton crater, at the lunar south pole, 21 kilometres across and with a rim 4 kilometres high. Because of the crater’s location, its rim is always in sunlight and so escapes the extreme temperature contrasts experienced on almost all the Moon’s surface — where the sun beats down for half of each month, followed by darkness in the other half. Moreover, there may be a lot of ice in the crater’s perpetually dark interior — crucial, of course, for sustaining a ‘colony’.

Mars

Mars is a more alluring but more remote target. I hope some people now living will walk on the Red Planet — as an adventure, and as a step towards the stars. But NASA will confront political obstacles in achieving this goal within a feasible budget. That’s mainly because the public requires it to be so risk-averse. The shuttle was launched over 130 times. Its two disastrous crashes were national traumas because it had unwisely been promoted as a safe vehicle for civilians (and a schoolteacher, Christa McAuliffe, was one of the casualties). Test pilots and adventurers would readily accept much more risk than this implicit 2 percent.

China has the resources, the dirigiste government, and maybe the willingness to undertake an Apollo-style programme. It already achieved a ‘first’ by landing on the far side of the Moon and will surely follow this up with a manned Lunar base. But a clearer-cut ‘great leap forward’ would involve footprints on Mars, not just on the Moon.

Leaving aside the Chinese, I think the future of manned spaceflight lies with privately funded adventurers, prepared to participate in a cut-price programme far riskier than western nations could impose on publicly supported civilians.

SpaceX, led by 2014 Lifeboat Guardian Award winner Elon Musk, has already docked with the ISS, and developed the techniques to recover and reuse the launch rocket’s first stage, presaging real cost savings. SpaceX, and the rival effort, Blue Origin, bankrolled by Jeff Bezos, will soon offer orbital flights to paying customers. These ventures bring a Silicon Valley culture into a domain long dominated by NASA and a few aerospace conglomerates.

The phrase ‘space tourism’ should be avoided. It lulls people into believing that such ventures are genuinely safe. And if that’s the perception, the inevitable accidents will be as traumatic as those of the Shuttle. These exploits must be ‘sold’ as dangerous sports, or intrepid exploration.

By 2100 thrill seekers in the mould of (say) Sir Ranolf Feinnes, may have established ‘bases’ on Mars. But don’t ever expect mass emigration from Earth. And here I disagree strongly with Musk and with my late Cambridge colleague 2008 Lifeboat Guardian Award winner Stephen Hawking who enthuse about rapid build-up of large-scale Martian communities. It’s a dangerous delusion to think that space offers an escape from Earth’s problems. We’ve got to solve these here. Coping with climate change may seem daunting, but it’s a doddle compared to terraforming Mars. No place in our solar system offers an environment even as clement as the Antarctic or the top of Everest. There’s no ‘Planet B’ for ordinary risk-averse people. We must cherish our Earthly home.

But we (and our progeny here on Earth) should cheer on the brave space adventurers, because they will have a pivotal role in shaping what happens in the twenty-second century and beyond.

Genetic and Cyborg Technologies

This is why. The space environment is inherently hostile for humans. Being ill-adapted to their new habitat, the pioneer Martian explorers will have a more compelling incentive than those of us on Earth to redesign themselves. They’ll harness the super-powerful genetic and cyborg technologies that will be developed in coming decades. These techniques will be, one hopes, heavily regulated on Earth, on prudential and ethical grounds. But ‘settlers’ on Mars will be far beyond the clutches of the regulators. We should wish them good luck in modifying their progeny to adapt to alien environments. It’s these space-faring adventurers, not those of us comfortably adapted to life on Earth, who will spearhead the posthuman era.

Finally, a word about the vast timespans of the cosmos. Our Solar system is 4.5 billion years old. It’s taken most of that time for humans to evolve from the first life-forms. But the Sun is less than half-way through its life — we’re a special species, but we’re not the culmination of evolution — maybe not even the half-way stage.

The Galaxy

Organic creatures need a planetary surface environment, but if posthumans make the transition to fully inorganic (electronic) intelligences, they won’t need an atmosphere. And they may prefer zero-g, especially for constructing extensive but lightweight habitats. So it’s in deep space — not on Earth, or even on Mars — that non-biological ‘brains’ may develop powers that humans can’t even imagine. The timescales for technological advances are but an instant compared to the timescales of the Darwinian natural selection that led to humanity’s emergence — and (more relevantly) they are less than a millionth of the vast expanses of cosmic time lying ahead. The outcome of this ‘secular intelligent design’ could spread through our Galaxy, and surpass humans by as much as we (intellectually) surpass slime mould.

We may colonize the galaxy.

But even in this cosmic perspective, the first steps away from our Earthly home are epochal events in the history of our planet — so it’s right that we should remember and celebrate the Apollo astronauts.