Right after the Big Bang, in the Planck epoch, the Universe occupied a space region with a radius of 1.4 × 10-13 cm – remarkably, equal to the fundamental length characterizing elementary particles. Analogue to the way nearly all cells contain the DNA information required to build the entire organism, every region the size of an elementary particle had then the energy necessary for the Universe’s creation.

As the Universe cooled down, electrons and quarks were the first to appear, the latter forming protons and neutrons, combining into nuclei in a mere matter of minutes. During its expansion, processes started happening slower and slower: it took 380,000 years for electrons to start orbiting around the nuclei, and 100 million years for hydrogen and helium to form the first stars. Even more, it wasn’t until 4.5 billion years ago that our young Earth was born, with its oceans emerging shortly after, and the first microbes to call them home for the first time. Life took over our planet in what seems, on the scale of the Universe, a sheer instant, and turned this world into its playground. There came butterflies and tricked the non-existence of natural blue pigment by creating Christmas tree-shaped nanometric structures in their wings to reflect blue’s wavelength only; fireflies and lanternfish which use the chemical reaction between oxygen and luciferin for bioluminescence; and it all goes all the way up to the butterfly effect leading to the unpredictability of the weather forecasts, commonly known as the reason why a pair of wings flapping in Brazil can lead to a typhoon in Texas. The world as we know it now developed slowly, and with the help of continuous evolution and natural selection, the first humans came to life.

Without any doubt, we are the earthly species never ceasing to surprise. We developed rationality, logic, strategic and critical thinking, yet human nature cannot be essentially defined without bringing into the equation our remarkable appetite for art and beauty. In the intricate puzzle human existence represents, this particular piece has given it valences no other known being possesses. Not all beauty is art, but many artworks both in the past, as well as today, embody some understanding of beauty.

To define is to limit, as Oscar Wilde stated, and even though we cannot establish clear definitions of art and beauty. Yet, great works of art manage to establish a strong thread between the creator and receptor. In contrast to this byproduct of human self-expression that encapsulates unique creative behaviour, beauty has existed long before our emergence as a species and isn’t bound to it in any way. It is omnipresent, a metaphorical Higgs field that can be observed by the ones who wish to open their eyes thoroughly. From the formation of Earth’s oceans and butterflies’ blue wings to Euler’s identity and rococo architecture, beauty is a subjective ubiquity. Though a question remains – why does it evoke such pleasure in our minds? What happens in our brains when we see something beautiful? The question is the subject of an entire field, named neuroaesthetics, which identified an intricate whole-brain response to artistic stimuli. As such, our puzzling reactions to art can be explained by these responses similar to “mind wandering”, involving “thoughts about the self, memory, and future”– in other words, art seems to evoke our past experiences, present conscious self, and imagination about the future. There needs to be noted that critics of the field draw attention to the superficiality and oversimplification that may characterize our attempts to view art through the lenses of neuroscience.

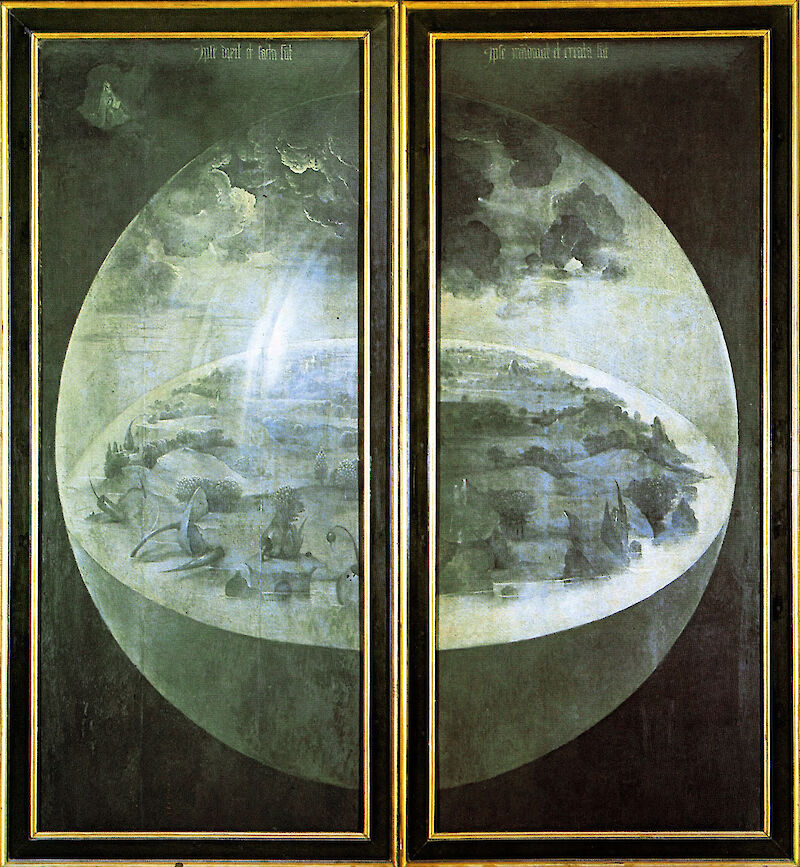

Withal, our fascination for art and beauty is certified by facts from immemorial times — let’s go back hundreds of thousands of years, even before language was invented. The past can prove our organic inclinations towards pleasing our senses and communicating ourselves to the world and posterity. Our ancestors felt the need to express themselves by designing exquisite quartz hand-axes, symmetrical teardrops which surpassed the pure functional purposes and represent the first artistic endeavours acknowledged. Around 100,000 years ago, the first jewellery (shell necklaces) were purposefully brought from the seashore as accessories for the early Homo sapiens in today’s Israel and Algeria. 60,000 years later, we marked the beginning of figurative art through the mammoth-ivory Löwenmensch found in today’s Germany, the oldest-known zoomorphic sculpture, half-human and half-lion. Just shortly after, we started depicting the reality of our everyday lives on cave walls: from cows, wild boars and domesticated dogs to dancing people and outlines of human hands; we told our stories the best we could, and we never stopped ever since.

We conferred the strongest of feelings to our workings, making them a powerful showcase of our minds and souls. Time gradually refined and sublimated our taste, going from Nefertiti’s bust to Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, up to the point where Robert Ryman’s ‘Bridge’– a white-on-white painting, a true reflection of minimalism – was sold for $20.6 million. But what are we heading towards?

The future holds the enticing promise of a legacy like no other: passing the artistic capabilities to machines, the ultimate step in making them human-like. How would this be possible since real art cannot catch contour without the touch of human creativity? The emergence of computational creativity aims to prove us that designing machines exhibiting creative behaviour is, in fact, a possibility that can be achieved. The earliest remarkable attempt was AARON, a computer program generating artworks with the help of AI, with its foundations put in 1968 by Harold Cohen. It continued to be improved until 2016, but regardless of the switch between C programming language to the more artistic-friendly Lisp, it was still restricted to hard coding and could not learn on its own. A giant leap was made after Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), first introduced in 2014, started being used for generating art. A noteworthy example is AICAN, “the first and only AI artist trained on 80,000 of the greatest works in art history”, its artworks having been exhibited in major New York galleries and dropping as NFTs in 2021. It is complemented by AIs that experiment with fragrances and flavours (such as the ones designed by IBM), or compose emotional soundtrack music (see AIVA). The artistic community allowed for other countless tasks to be taken over by AIs; take ArtPI, an API optimized for visual searching based on style, color, light, composition, genre and other characteristics. The world seeks to improve whatever can be improved, technology mimicking whatever can be mimicked, never seeming to run out of options and ideas.

For an indefinite period of time, we will continue to assimilate and replicate the world’s astonishing beauty, transposing it into art and eventually passing it on to machines. This idea of continuity is deeply rooted in human nature, giving us hope for the much-yearned transcendence: we want to feel that we can overcome our transience, loneliness, fears, and limitations. And art is here, for humans and posthumans alike, to serve this purpose for as long as we need it and yield beauty as never seen before.