“By combining different feedstocks, like metal and ceramics, in the printing process, we found that the final material is really sensitive to the environment,” said Sizhe Xu. [ https://www.labroots.com/trending/space/30260/3d-printing-mo…habitats-2](https://www.labroots.com/trending/space/30260/3d-printing-mo…habitats-2)

How can lunar regolith be used to construct future habitats on the Moon? This is what a recent study published in Acta Astronautica hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated novel methods for using lunar regolith for making structures on the lunar surface. This study has the potential to help scientists, engineers, mission planners, and future astronauts develop methods for working and living on the Moon, which comes as NASA’s Artemis program plans to land humans on the Moon in 2028.

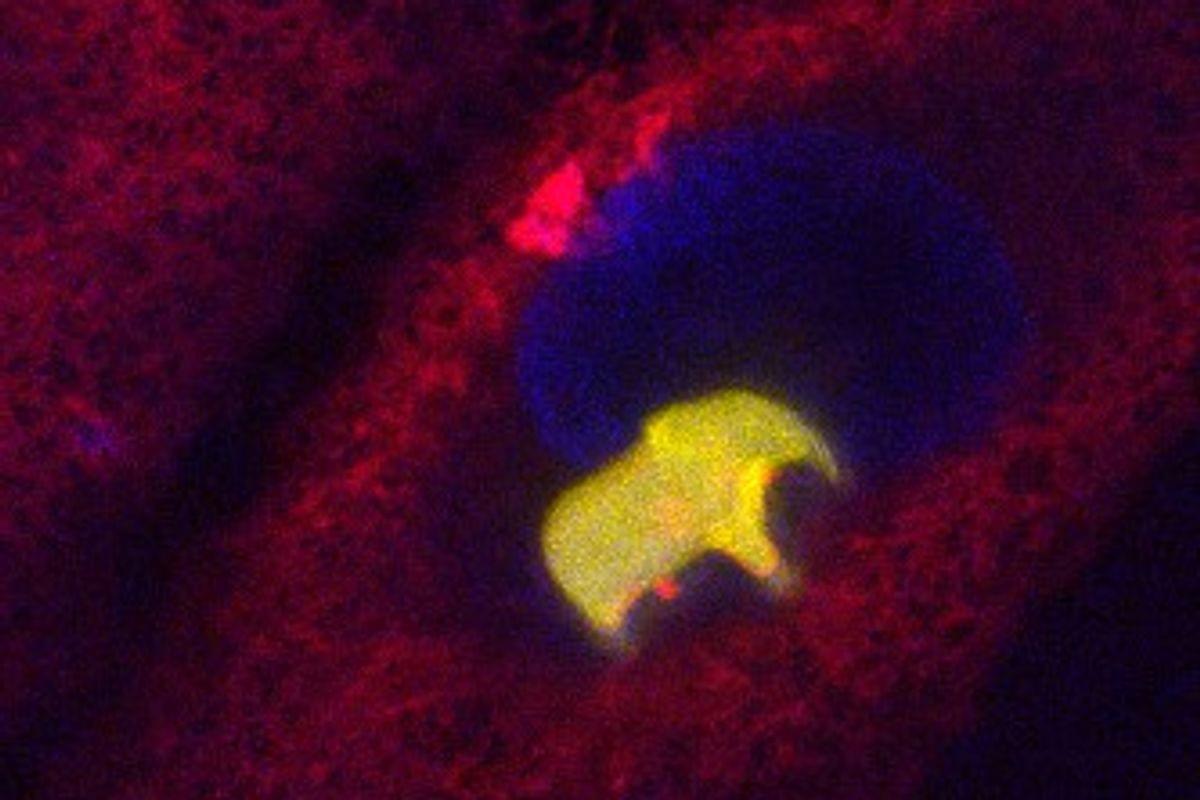

For the study, the researchers examined how a laser 3D printing method called laser directed energy deposition (LDED) could be used for manufacturing structures using lunar simulant under a myriad of environments, specifically lunar conditions of zero atmosphere, oxygen, and complete vacuum. The lunar simulant used for the experiments is known as LHS-1 (lunar highland regolith simulants), with the lunar highlands being the lighter-colored mountainous regions of the Moon as seen from Earth, as opposed to the volcanic regions of the Moon that are darker in appearance.

Along with the environmental conditions, the researchers also examined how printing LHS-1 on various types of surfaces yielded different results. They also examined laser speed, scanning power, and the final microstructure products. In the end, the researchers found that alumina-silicate ceramic surfaces and high temperatures produced the most promising structures but cautioned that laboratory conditions vary from the real-world environment on the Moon.