The public could be frightened or skeptical. A lot depends on how scientists announce it—if they ever find life in space.

In a new study published in Physical Review Letters, scientists have performed the first global simulations of monster shocks—some of the strongest shocks in the universe—revealing how these extreme events in magnetar magnetospheres could be responsible for producing fast radio bursts (FRBs).

Magnetars are young neutron stars with extremely strong magnetic fields, reaching up to 1015 Gauss on their surfaces. These cosmic powerhouses produce prolific X-ray activity and have emerged as candidates for explaining FRBs, mysterious millisecond-duration radio bursts detected from across the cosmos. The connection between magnetars and FRBs was strengthened in 2020 when a simultaneous X-ray and radio burst was observed from the galactic magnetar SGR 1935+2154.

The study explores monster shock formation in realistic magnetospheric geometry and was led by Dominic Bernardi, a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis.

An AI just helped guide a NASA rover across Mars, marking a major leap in autonomous space exploration. 🚀

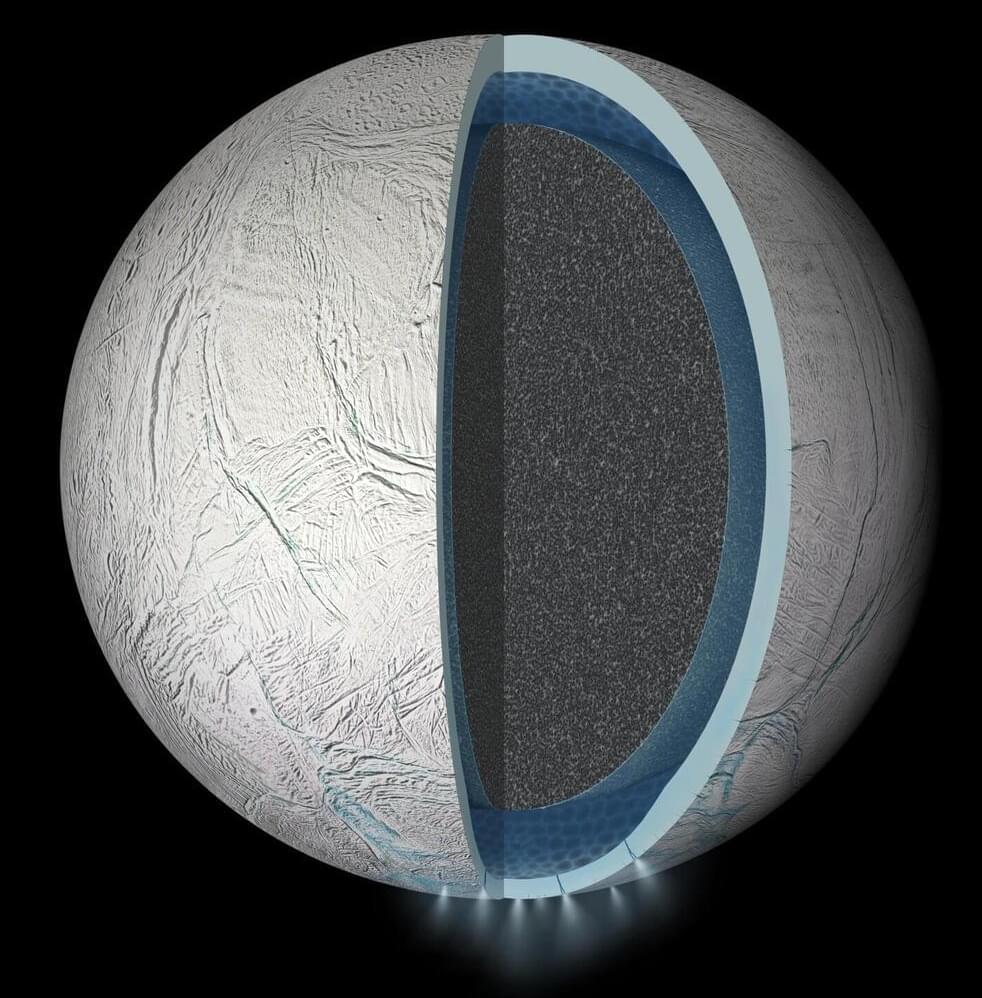

Through new experiments, researchers in Japan and Germany have recreated the chemical conditions found in the subsurface ocean of Saturn’s moon, Enceladus. Published in Icarus, the results show that these conditions can readily produce many of the organic compounds observed by the Cassini mission, strengthening evidence that the distant world could harbor the molecular building blocks of life.

Beneath its thick outer shell of ice, astronomers widely predict that Saturn’s sixth largest moon hosts an ocean of liquid water in its south polar region. The main evidence for this ocean is a water-rich plume which frequently erupts from fractures in Enceladus’ surface, leaving a trail of ice particles in its orbital paths which contributes to one of its host planet’s iconic rings.

Between 2004 and 2017, NASA’s Cassini probe passed through this E-ring and plume several times. Equipped with instruments including mass spectrometers and an ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, it detected a diverse array of organic compounds: from simple carbon dioxide to larger hydrocarbon chains, which on Earth are essential molecular precursors to complex biomolecules.

Bach reframes AI as the endpoint of a long philosophical project to “naturalize the mind,” arguing that modern machine learning operationalizes a lineage from Aristotle to Turing in which minds, worlds, and representations are computational state-transition systems. He claims computer science effectively re-discovers animism—software as self-organizing, energ†y-harvesting “spirits”—and that consciousness is a simple coherence-maximizing operator required for self-organizing agents rather than a metaphysical mystery. Current LLMs only simulate phenomenology using deepfaked human texts, but the universality of learning systems suggests that, when trained on the right structures, artificial models could converge toward the same internal causal patterns that give rise to consciousness. Bach proposes a biological-to-machine consciousness framework and a research program (CIMC) to formalize, test, and potentially reproduce such mechanisms, arguing that understanding consciousness is essential for culture, ethics, and future coexistence with artificial minds.

Key takeaways.

▸ Speaker & lens: Cognitive scientist and AI theorist aiming to unify philosophy of mind, computer science, and modern ML into a single computationalist worldview.

▸ AI as philosophical project: Modern AI fulfills the ancient ambition to map mind into mathematics; computation provides the only consistent language for modeling reality and experience.

▸ Computationalist functionalism: Objects = state-transition functions; representations = executable models; syntax = semantics in constructive systems.

▸ Cyber-animism: Software as “spirits”—self-organizing, adaptive control processes; living systems differ from dead ones by the software they run.

▸ Consciousness as function: A coherence-maximizing operator that integrates mental states; second-order perception that stabilizes working memory; emerges early in development as a prerequisite for learning.

▸ LLMs & phenomenology: Current models aren’t conscious; they simulate discourse about consciousness using data full of “deepfaked” phenomenology. A Turing test cannot detect consciousness because performance ≠ mechanism.

▸ Universality hypothesis: Different architectures optimized for the same task tend to converge on similar internal causal structures; suggests that consciousness-like organization could arise if it’s the simplest solution to coherence and control.

▸ Philosophical zombies: Behaviorally identical but non-conscious agents may be more complex than conscious ones; evolution chooses simplicity → consciousness may be the minimal solution for self-organized intelligence.

▸ Language vs embodiment: Language may contain enough statistical structure to reconstruct much of reality; embodiment may not be strictly necessary for convergent world models.

▸ Testing for machine consciousness: Requires specifying phenomenology, function, search space, and success criteria—not performance metrics.

▸ CIMC agenda: Build frameworks and experiments to recreate consciousness-like operators in machines; explore implications for ethics, interfaces, and coexistence with future minds.

Space Renaissance International (SRI) is a Permanent Observer at the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). We are currently advocating for: Ownership of resources removed from in place (being considered by the COPUOS Working Group on the Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activity); Permanent advisory status for the private sector in Read More

You can tell a lot about a material based on the type of light shining at it: Optical light illuminates a material’s surface, while X-rays reveal its internal structures and infrared captures a material’s radiating heat. Now, MIT physicists have used terahertz light to reveal inherent, quantum vibrations in a superconducting material, which have not been observable until now.

Terahertz light is a form of energy that lies between microwaves and infrared radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum. It oscillates over a trillion times per second—just the right pace to match how atoms and electrons naturally vibrate inside materials. Ideally, this makes terahertz light the perfect tool to probe these motions.

But while the frequency is right, the wavelength—the distance over which the wave repeats in space—is not. Terahertz waves have wavelengths hundreds of microns long. Because the smallest spot that any kind of light can be focused into is limited by its wavelength, terahertz beams cannot be tightly confined.

Scientists say a real warp drive may no longer be pure science fiction, thanks to new breakthroughs in theoretical physics. Recent studies suggest space itself could be compressed and expanded, allowing faster-than-light travel without breaking known laws of physics. Unlike sci-fi engines, this concept wouldn’t move a ship through space — it would move space around the ship. Researchers are now exploring how energy, gravity, and exotic matter could make this possible. In this video, we explain how a warp drive could work and how close science really is.

Credit:

Star Wars: Episode VIII — The Last Jedi / Lucasfilm https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2527336/.… Trek Beyond / Paramount Pictures https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2660888/.… Lost in Space / New Line Cinema https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120738/.… Parker Solar Probe touches the Sun: By NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Ben Smith — https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14036, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… Parker Solar Probe: By NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio — Johns Hopkins University/APL/Betsy Congdon, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Yanping Guo, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/John Wirzburger, NASA/Nicola Fox, NASA/Kelly Korreck, Johns Hopkins University/APL/Nour Raouafi, NASA/Joseph Westlake, eMITS/Joy Ng, eMITS/Beth Anthony, eMITS/Lacey Young, ADNET Systems, Inc./Aaron E. Lepsch — https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14741, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… Parker Solar Probe: By NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben — http://parkersolarprobe.jhuapl.edu/Mu…, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index… Vertical Testbed Rocket: By NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center — https://www.nasa.gov/armstrong/, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… […]cket_(AFRC-2017–11349-1_Masten-COBALT-UnTetheredFLT1).webm Interstellar / Paramount Pictures Stargate / Canal+ CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.… Alcubierre: By AllenMcC., https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index… Miguel alcubierre: By Jpablo.romero, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index… Water wave analogue of Casimir effect: By Denysbondar, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… Casimir plates: By Emok, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index… CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.… Proxima Centauri b: By ESO/Konstantino Polizois/Nico Bartmann — http://www.eso.org/public/unitedkingd…, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… WARP Reactor Concept Movie: By WarpingSpacetime, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… Ag Micromirrors: By Simpik, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… Animation is created by Bright Side.

Star Trek Beyond / Paramount Pictures https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2660888/.…

Lost in Space / New Line Cinema https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120738/.…

Parker Solar Probe touches the Sun: By NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Ben Smith — https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14036, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Parker Solar Probe: By NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio — Johns Hopkins University/APL/Betsy Congdon, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Yanping Guo, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/John Wirzburger, NASA/Nicola Fox, NASA/Kelly Korreck, Johns Hopkins University/APL/Nour Raouafi, NASA/Joseph Westlake, eMITS/Joy Ng, eMITS/Beth Anthony, eMITS/Lacey Young, ADNET Systems, Inc./Aaron E. Lepsch — https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14741, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Parker Solar Probe: By NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben — http://parkersolarprobe.jhuapl.edu/Mu…, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

Vertical Testbed Rocket: By NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center — https://www.nasa.gov/armstrong/, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi… […]cket_(AFRC-2017–11349-1_Masten-COBALT-UnTetheredFLT1).webm.

Interstellar / Paramount Pictures.

Stargate / Canal+

CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.…

Alcubierre: By AllenMcC., https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

Miguel alcubierre: By Jpablo.romero, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

Water wave analogue of Casimir effect: By Denysbondar, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Casimir plates: By Emok, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.…

Proxima Centauri b: By ESO/Konstantino Polizois/Nico Bartmann — http://www.eso.org/public/unitedkingd…, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

WARP Reactor Concept Movie: By WarpingSpacetime, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Ag Micromirrors: By Simpik, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Animation is created by Bright Side.

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory are breathing new life into the scientific understanding of neptunium, a unique, radioactive, metallic element—and a key precursor for production of the plutonium-238, or Pu-238, that fuels exploratory spacecraft.

The ORNL team’s research arrives during a period of increased national interest in the use of Pu-238 in radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs. Often used in space missions such as NASA’s Perseverance Rover for long-term power, RTGs convert heat from radioactive decay into electricity. Advancing RTG knowledge and application possibilities also requires the same high-level evaluation of both chemical reactions and structural characterization, two key aspects of the materials science for which ORNL is known.

“When people want to do scientific experiments in space, they need something to power their instruments, and plutonium is typically the power source because things like solar and lithium ion batteries don’t withstand deep space,” said Kathryn Lawson, radiochemist in ORNL’s Fuel Cycle Chemical Technology Group and lead author of the new study.