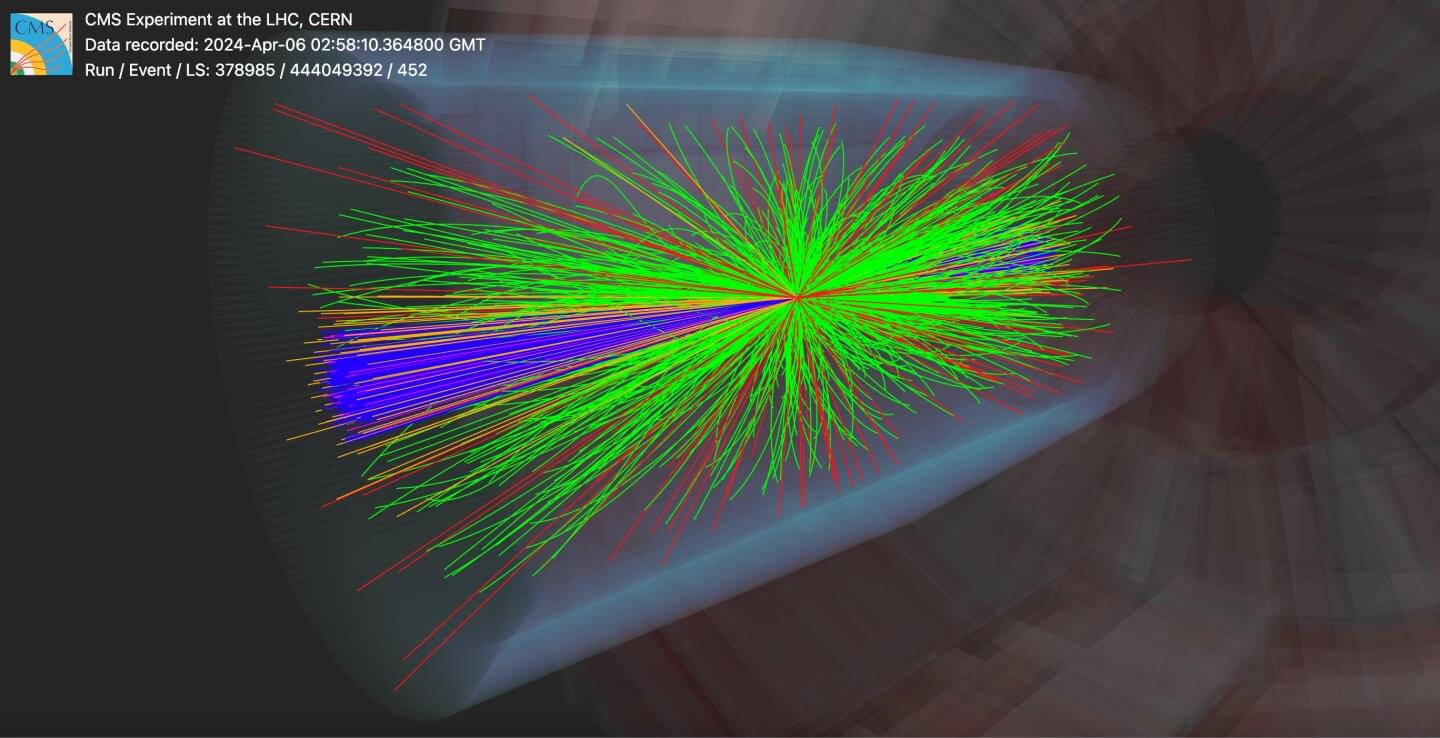

The CMS Collaboration has shown, for the first time, that machine learning can be used to fully reconstruct particle collisions at the LHC. This new approach can reconstruct collisions more quickly and precisely than traditional methods, helping physicists better understand LHC data. The paper has been submitted to the European Physical Journal C and is currently available on the arXiv preprint server.

Each proton–proton collision at the LHC sprays out a complex pattern of particles that must be carefully reconstructed to allow physicists to study what really happened. For more than a decade, CMS has used a particle-flow (PF) algorithm, which combines information from the experiment’s different detectors, to identify each particle produced in a collision. Although this method works remarkably well, it relies on a long chain of hand-crafted rules designed by physicists.

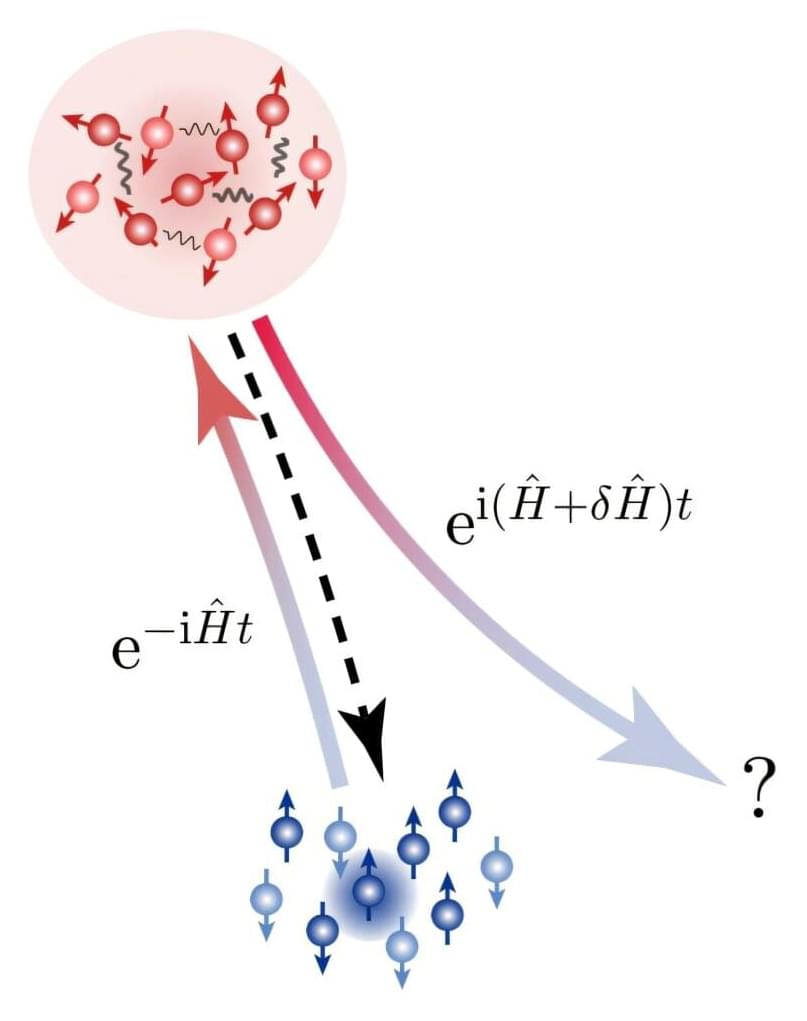

The new CMS machine-learning-based particle-flow (MLPF) algorithm approaches the task fundamentally differently, replacing much of the rigid hand-crafted logic with a single model trained directly on simulated collisions. Instead of being told how to reconstruct particles, the algorithm learns how particles look in the detectors, like how humans learn to recognize faces without memorizing explicit rules.