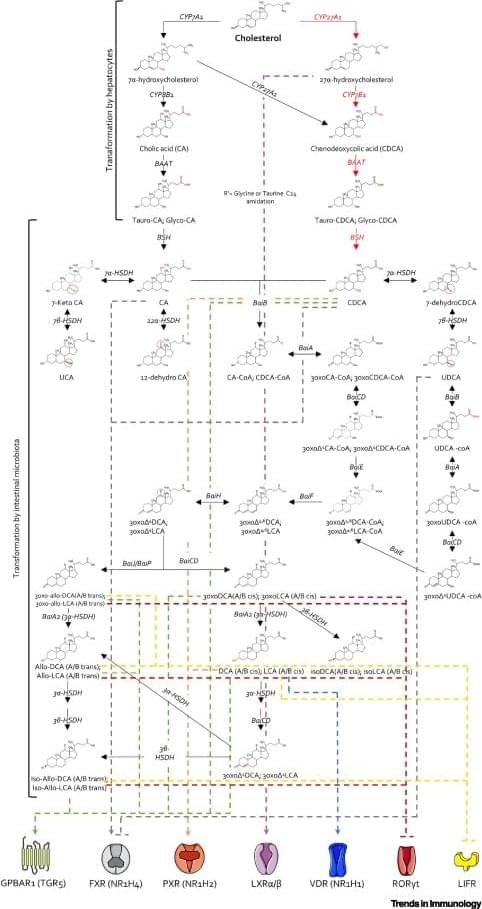

The human liver makes two primary bile acids that are cholesterol derivates, while, intestinal microbiota is the source of hundreds of secondary bile acids and microbially conjugated bile acids.

A dysbiotic microbiota releases altered quantities and varieties of secondary bile acids, which contribute to intestinal and systemic immune dysregulation.

In this review the authors discuss recent advances in secondary bile acids, the intestinal microbiota generating them, and their role in immune disorders. sciencenewshighlights ScienceMission https://sciencemission.com/Secondary-bile-acids

Bile acids are cholesterol derivatives, generated by the coordinated intervention of human and bacterial genes, functioning as endogenous ligands for multiple transcription factors and receptors throughout the body. While only two primary bile acids are generated by the human liver, the intestinal microbiota is the source of hundreds of secondary bile acids and microbially conjugated bile acids. Secondary bile acids regulate immune function throughout the body, promote the conversion of thyroid hormone, and regulate energy expenditure in muscle and adipose tissues, ultimately contributing to the beneficial effects of calorie restriction on human health and longevity. Here, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of secondary bile acids, the intestinal microbiota generating them, and their role in immune disorders.