Our planet plunged into one of the most dramatic climate states in its long history, approximately 720–635 million years ago. During a period geologists call Snowball Earth, ice sheets crept from the poles all the way to the tropics, covering the oceans and continents in a nearly global freeze.

Evidence for this extreme climate comes from rock formations around the world that bear the signatures of ancient glaciers at low latitudes—signs that Earth’s surface was encased in ice far beyond what we see in today’s polar regions.

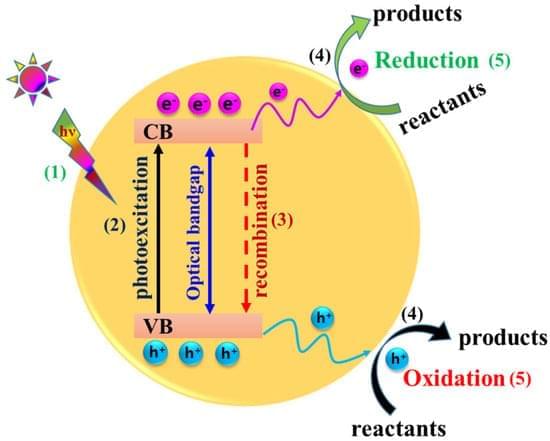

Scientists have long studied how a feedback process known as ice-albedo helped lock in and amplify this deep chill. Albedo is a measure of how much sunlight a surface reflects; snow and ice are bright and reflect most of the sun’s energy back into space, cooling the planet further as more of it spreads across the surface.