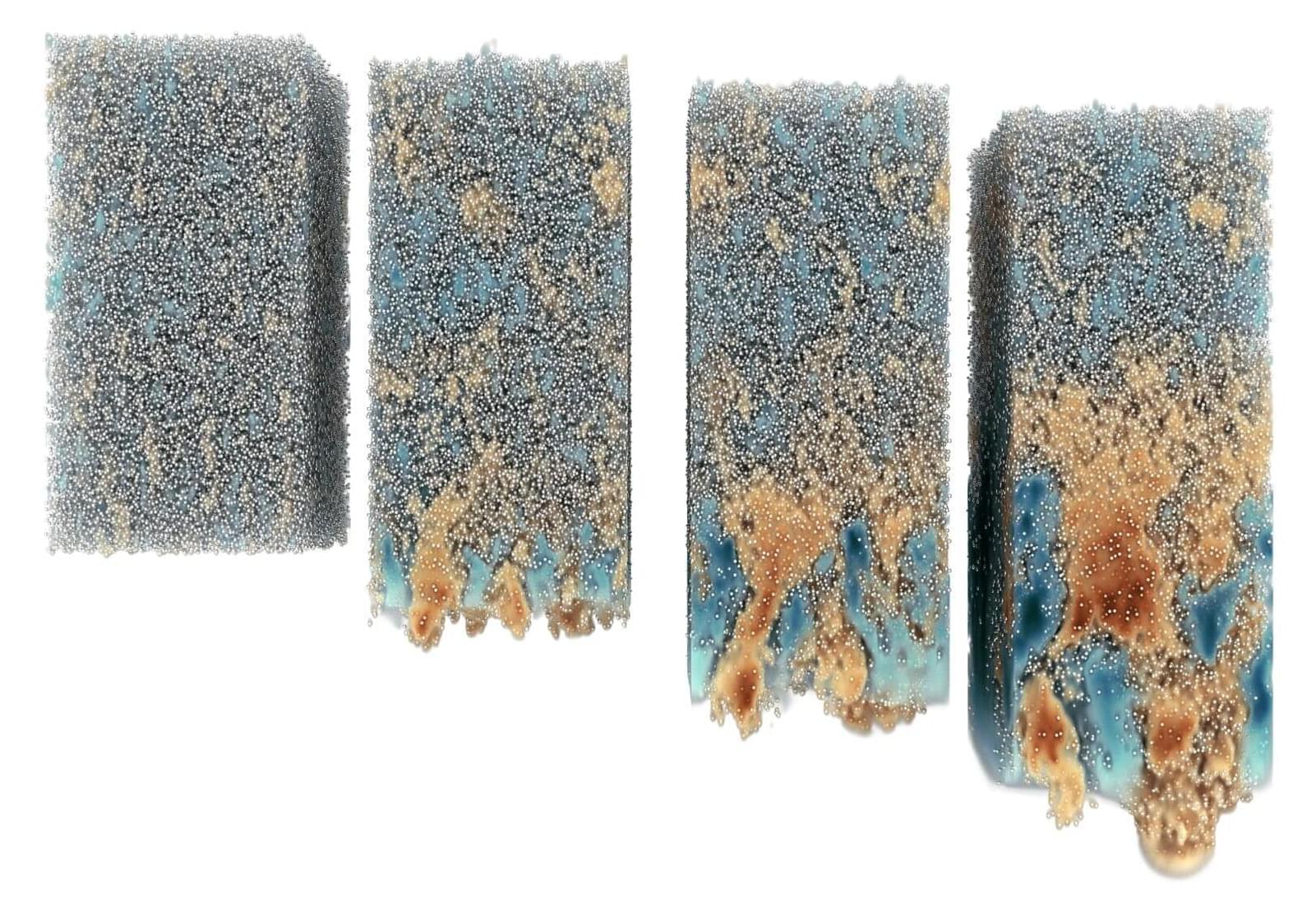

What governs the speed at which raindrops fall, sediment settles in river estuaries, and matter is ejected during a supernova? These questions circle around one, deceitfully simple factor: the rate at which a fluid filled with particles mixes with a particle-free one. Raindrops travel from one layer of air to another; sediment falls from river to seawater, and ejecta travels from the exploding star through the surrounding dust cloud. The same principle dictates sediment mixing in rising smoke, dust storms, nuclear explosions, hydrocarbon refining, metal smelting, wastewater treatment, and more.

New simulations have now provided researchers and engineers with unprecedented access to these fundamental fluid mechanics. While plainly visible in everyday life, the phenomenon has eluded scientific scrutiny due to their complexity. For the first time, researchers have derived a general formulation of how layers of heavy particles mix and described the common characteristics of the phenomena.

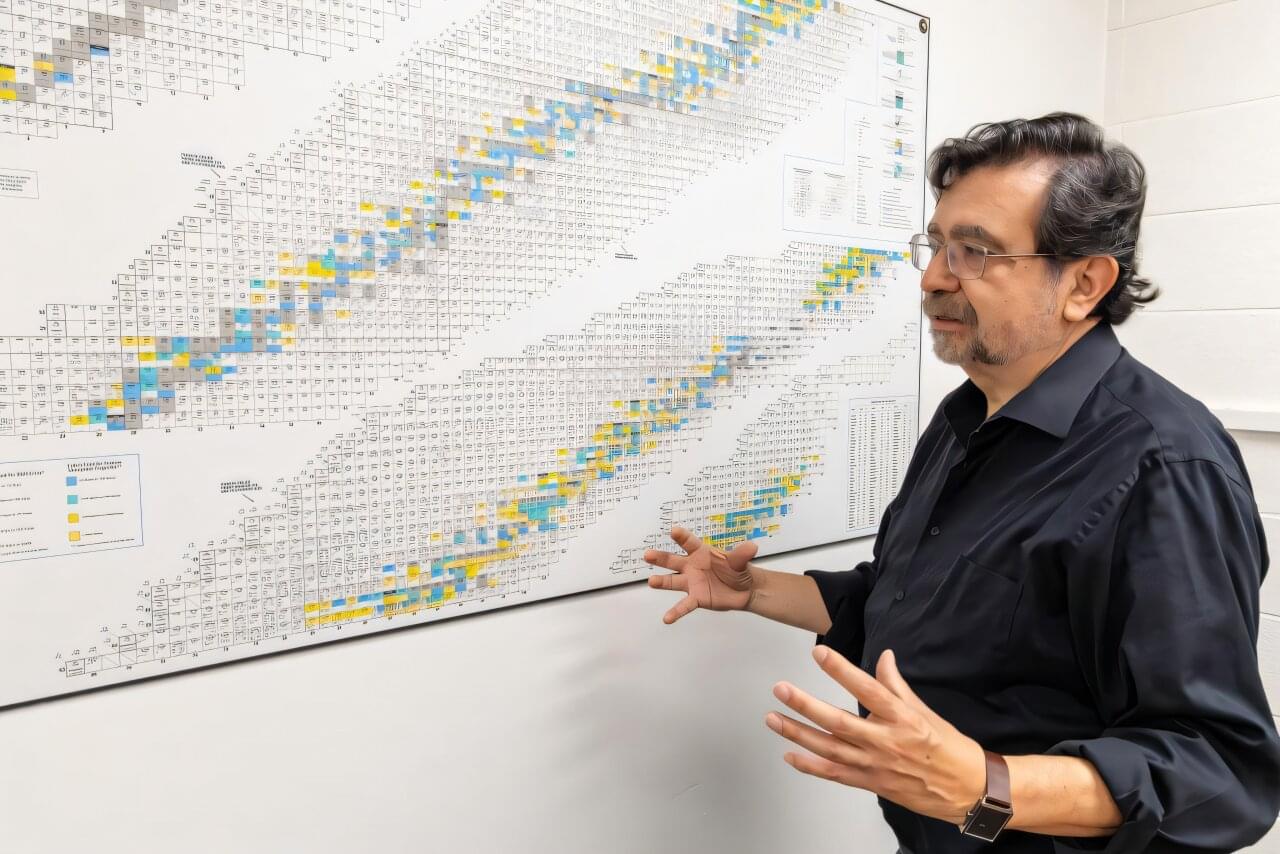

Simone Tandurella, study first author and Ph.D. student in the Complex Fluids and Flows Unit at OIST, explains, “Both the simulations and the model we obtain enable exciting research into a wide range of fundamental physics phenomena, as well as applied research in fluid engineering. They provide the basic puzzle pieces that can help us understand fluid-particle instabilities at large scales.”