A new research paper was published by Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as “Aging (Albany NY)” and “Aging-US” by Web of Science) in Volume 15, Issue 15, entitled, “Associations between klotho and telomere biology in high stress caregivers.”

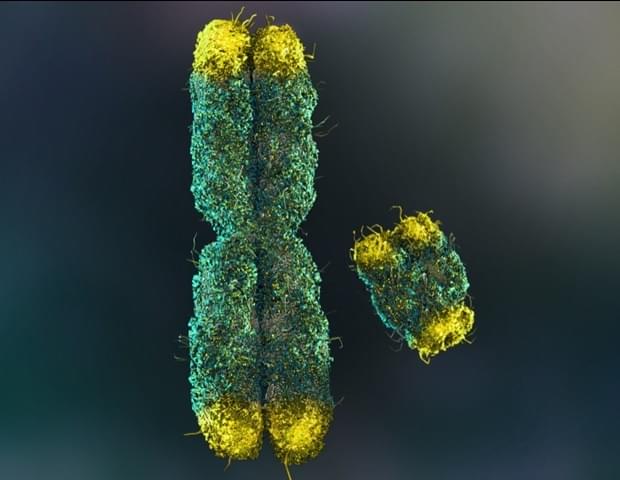

Aging biomarkers may be related to each other through direct co-regulation and/or through being regulated by common processes associated with chronological aging or stress. Klotho is an aging regulator that acts as a circulating hormone with critical involvement in regulating insulin signaling, phosphate homeostasis, oxidative stress, and age-related inflammatory functioning.

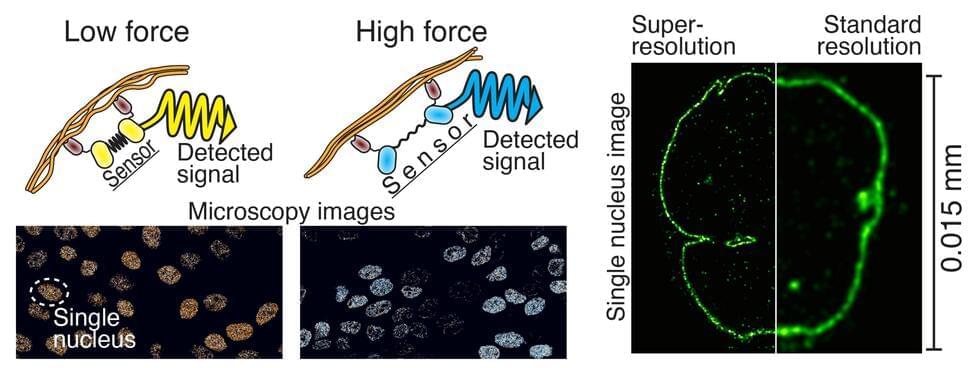

In this new study, researchers Ryan L. Brown, Elissa E. Epel, Jue Lin, Dena B. Dubal, and Aric A. Prather from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of California, San Francisco, and the Department of Neurology and Weill Institute of Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco discuss the association between klotho levels and telomere length of specific sorted immune cells among a healthy sample of mothers caregiving for a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or a child without ASD — covarying age and body mass index — in order to understand if high stress associated with caregiving for a child with an ASD may be involved in any association between these aging biomarkers.