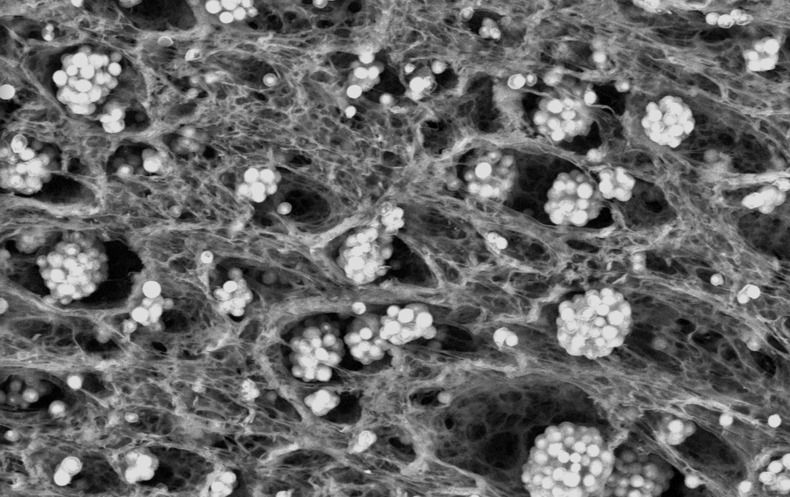

Wherever there are people, the party is sure to follow. Well, a party of microbes, at least. That is what scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have found after a 30-day microbial observation of the inflatable lunar/Mars analog habitat (IMAH).

What is an “analog habitat?” For NASA, analogs are experiments and processes that are developed and tested on the ground in the confines of special laboratories on Earth. Because of the danger, distance, and expense of space flight, it makes good sense to test out conditions that space travelers will face — before they ever launch.

For NASA, there are five different space stresses evaluated in analog missions. These stresses are the subject of analog missions that often make use of a carefully designed habitat to replicate space conditions. These five challenges are: