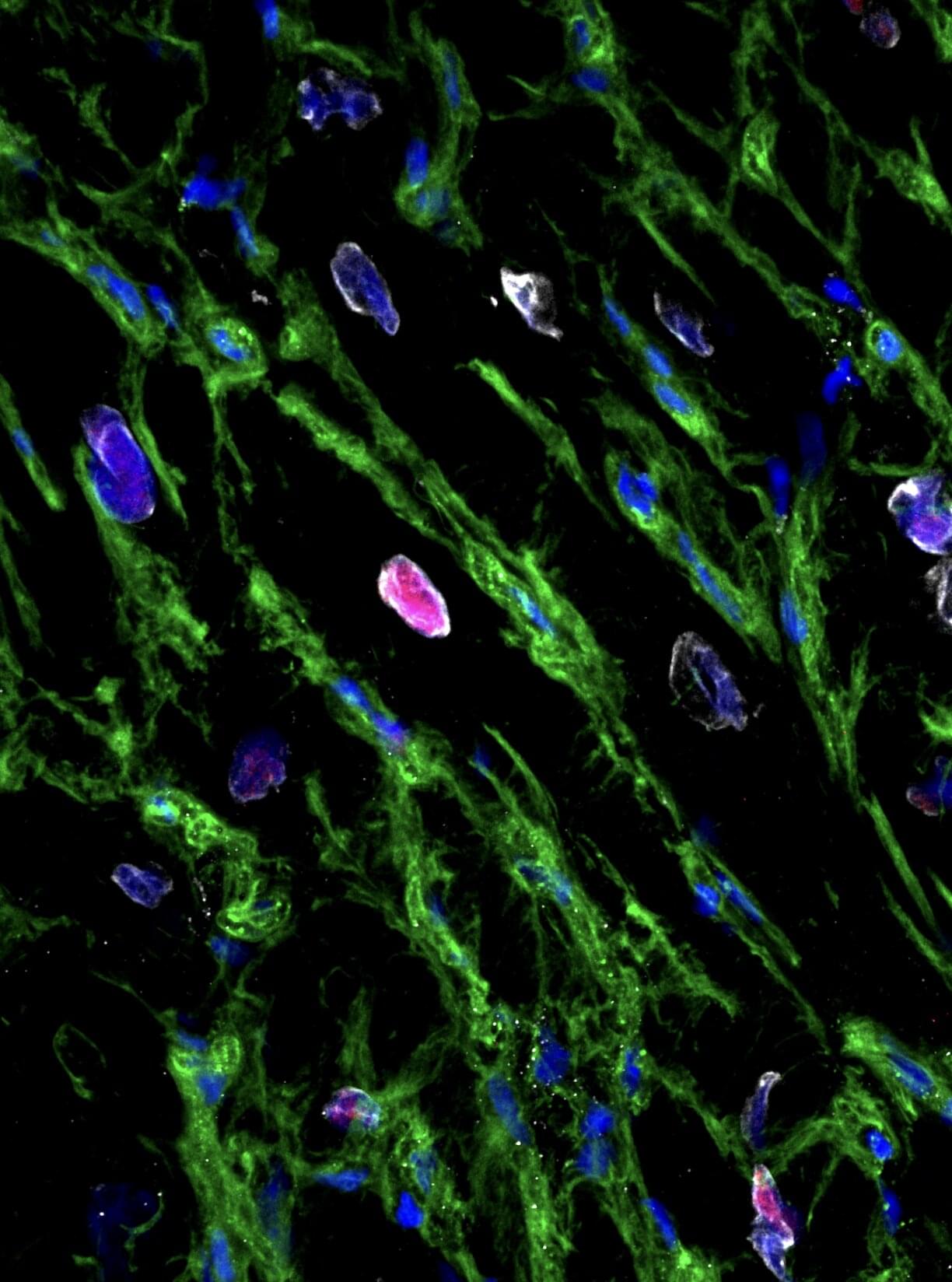

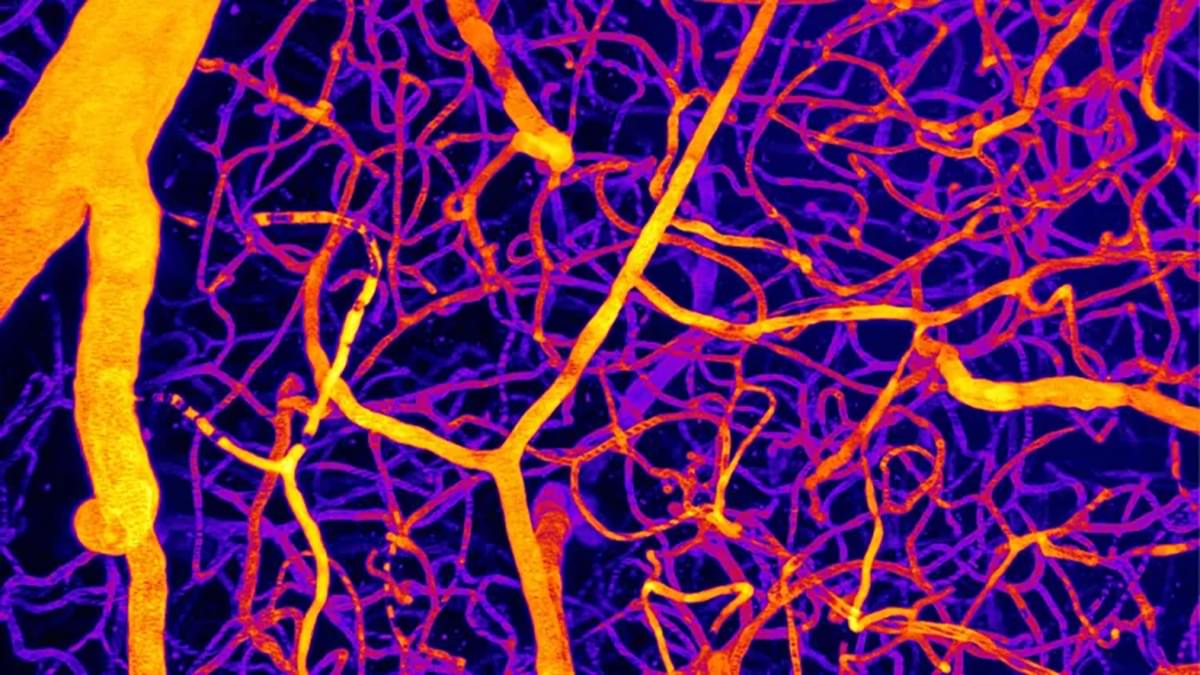

This study provides the first direct evidence of cardiomyocyte mitosis in the adult human heart following myocardial infarction, challenging the long-standing paradigm that cardiac muscle cells are incapable of regeneration. Utilizing live human heart tissue models, researchers from the University of Sydney demonstrated that while fibrotic scarring occurs post-ischemia, the heart simultaneously initiates a natural regenerative program characterized by active cell division. The investigation further identified specific regulatory proteins that drive this mitotic process, offering a molecular blueprint for endogenous tissue repair. These findings suggest that the human heart possesses a latent regenerative capacity that could be therapeutically harnessed to prevent heart failure and reverse post-infarct tissue damage, representing a significant shift in regenerative cardiovascular medicine.

A world‑first University of Sydney study reveals that the human heart can regrow muscle cells after a heart attack, paving the way for breakthrough regenerative therapies to reverse heart failure.