Yay:3 death can be reversed at a cellular level and then regenerate it back to health.

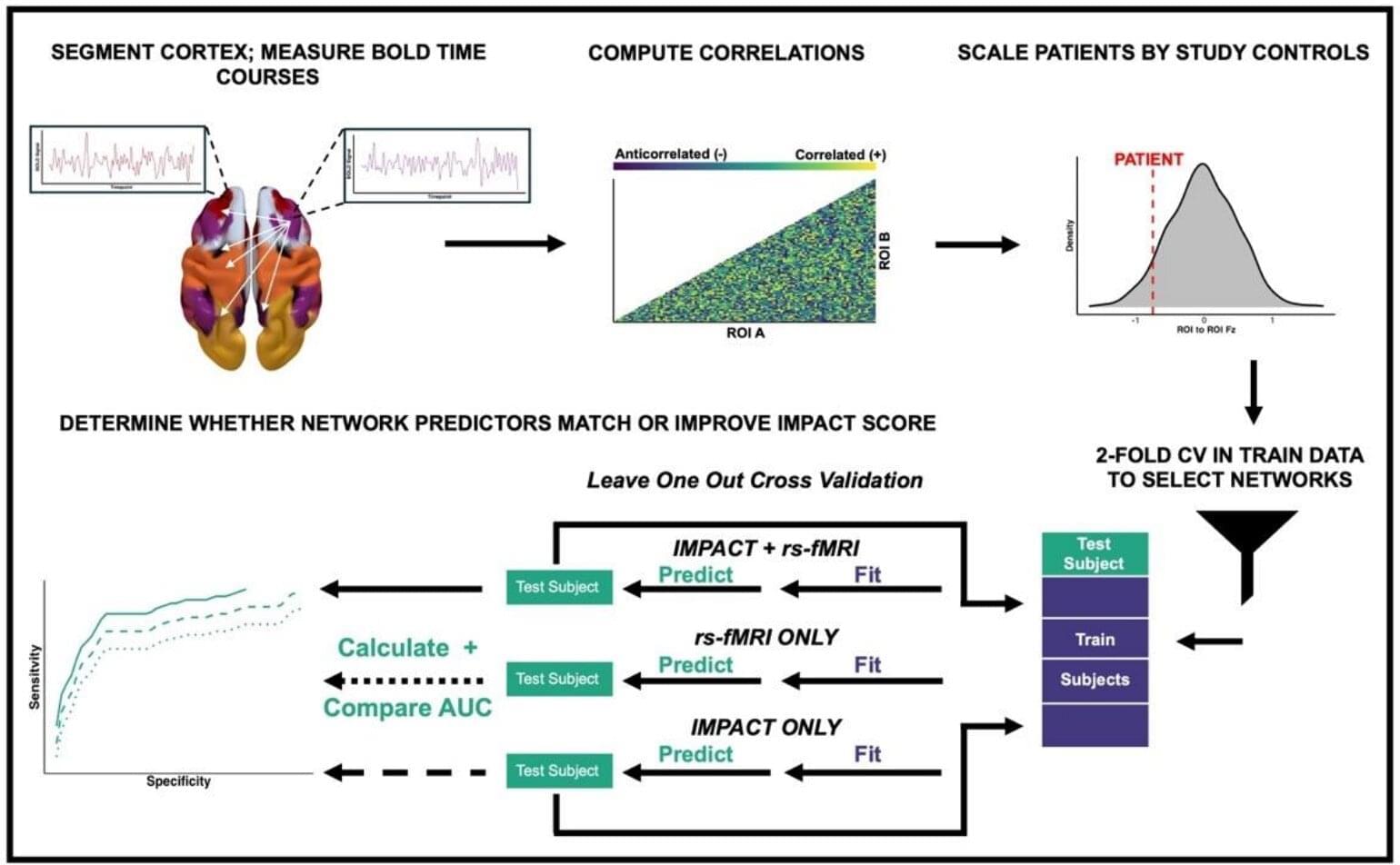

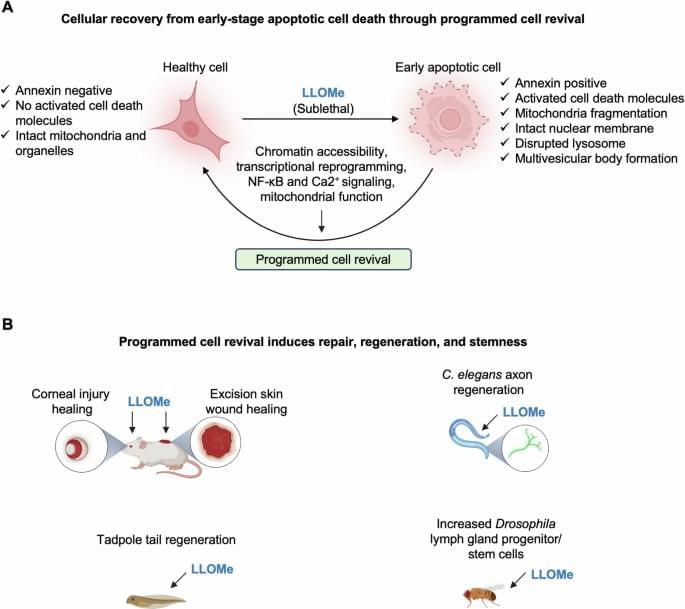

Therefore, in this issue of The EMBO Journal, Dhar et al sought to improve our understanding of the key molecular mechanisms that regulate the reversal of cell death and apply this knowledge to tissue repair (Dhar et al, 2025). In their study, the authors used a sublethal dose of the lysosomotropic agent L-Leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester (LLOMe) to induce apoptotic cell death (Johansson et al, 2010) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and characterize the cell revival process. At the initial stage following LLOMe treatment, cells detach from the growth surface and display an apoptotic phenotype, suggesting they are undergoing cell death. However, at later stages, most of the floating cells reattach and regain their typical morphology, with a reduction in the activation of cell death molecules (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that cells can recover from the brink of cell death in response to LLOMe. This phenomenon occurs in multiple non-immune cell types, including primary MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts, as well as several cell lines from hamsters, mice, and humans (Dhar et al, 2025).

At the organellar level, shortly after treatment with LLOMe, microtubules, mitochondria, Golgi, and the endoplasmic reticulum are fragmented; however, these structures progressively recover within 2–3 h and return to near-normal morphology by 16 h post-treatment. Additionally, reviving cells display dramatic changes in endosomes, autophagosomes, and lysosomes, including the formation of abnormally large EEA1-positive early endosomes, LC3-positive autophagosomes, and Rab7/lysotracker-positive acidic vacuoles resembling multivesicular bodies. These large acidic compartments are enzymatically active and frequently surrounded by mitochondrial networks during revival, suggesting a role for metabolic support in driving the recovery.