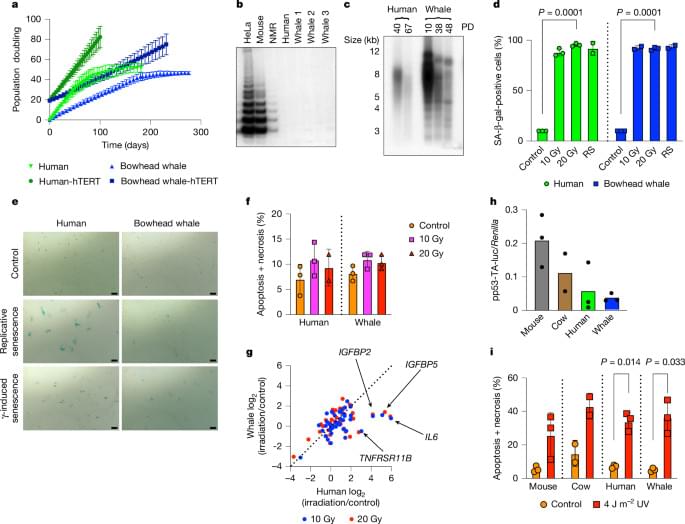

At more than 200 years, the maximum lifespan of the bowhead whale exceeds that of all other mammals. The bowhead is also the second-largest animal on Earth1, reaching over 80,000 kg. Despite its very large number of cells and long lifespan, the bowhead is not highly cancer-prone, an incongruity termed Peto’s paradox2.

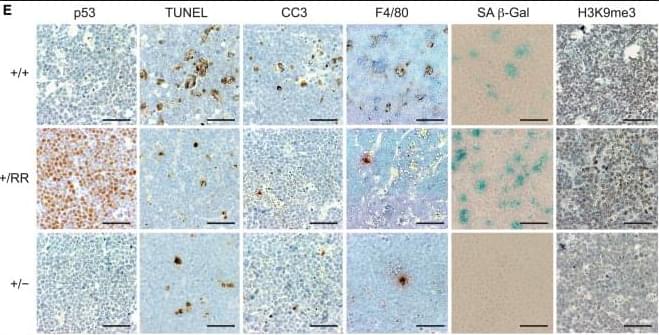

Here, to understand the mechanisms that underlie the cancer resistance of the bowhead whale, we examined the number of oncogenic hits required for malignant transformation of whale primary fibroblasts. Unexpectedly, bowhead whale fibroblasts required fewer oncogenic hits to undergo malignant transformation than human fibroblasts. However, bowhead whale cells exhibited enhanced DNA double-strand break repair capacity and fidelity, and lower mutation rates than cells of other mammals. We found the cold-inducible RNA-binding protein CIRBP to be highly expressed in bowhead fibroblasts and tissues.

Bowhead whale CIRBP enhanced both non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination repair in human cells, reduced micronuclei formation, promoted DNA end protection, and stimulated end joining in vitro. CIRBP overexpression in Drosophila extended lifespan and improved resistance to irradiation. These findings provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that, rather than relying on additional tumour suppressor genes to prevent oncogenesis3,4,5, the bowhead whale maintains genome integrity through enhanced DNA repair. This strategy, which does not eliminate damaged cells but faithfully repairs them, may be contributing to the exceptional longevity and low cancer incidence in the bowhead whale.

Analysis of the longest-lived mammal, the bowhead whale, reveals an improved ability to repair DNA breaks, mediated by high levels of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein.