U.S. health regulators gave early approval to a new Alzheimer’s drug from Eisai Co. and Biogen Inc., the most promising to date in a new class of medicines that may help slow cognitive decline caused by the disease.

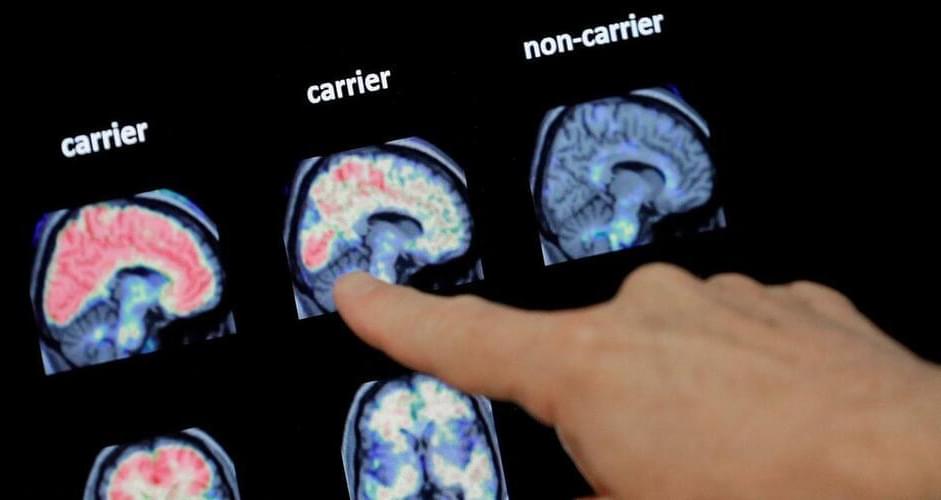

The Food and Drug Administration granted conditional approval to the drug, called lecanemab, based on an early study finding it reduced levels of a sticky protein called amyloid from the brains of people with early-stage Alzheimer’s. The companies will sell it under the brand name Leqembi.