For millions living with nerve pain, even a light touch can feel unbearable. Scientists have long suspected that damaged nerve cells falter because their energy factories known as mitochondria don’t function properly.

Now research published in Nature suggests a way forward: supplying healthy mitochondria to struggling nerve cells.

Using human tissue and mouse models, researchers found that replenishing mitochondria significantly reduced pain tied to diabetic neuropathy and chemotherapy-induced nerve damage. In some cases, the relief lasted up to 48 hours.

Instead of masking symptoms, the approach could fix what the team sees as the root problem — restoring the energy flow that keeps nerve cells healthy and resilient.

“By giving damaged nerves fresh mitochondria — or helping them make more of their own — we can reduce inflammation and support healing,” said the study’s senior author. “This approach has the potential to ease pain in a completely new way.

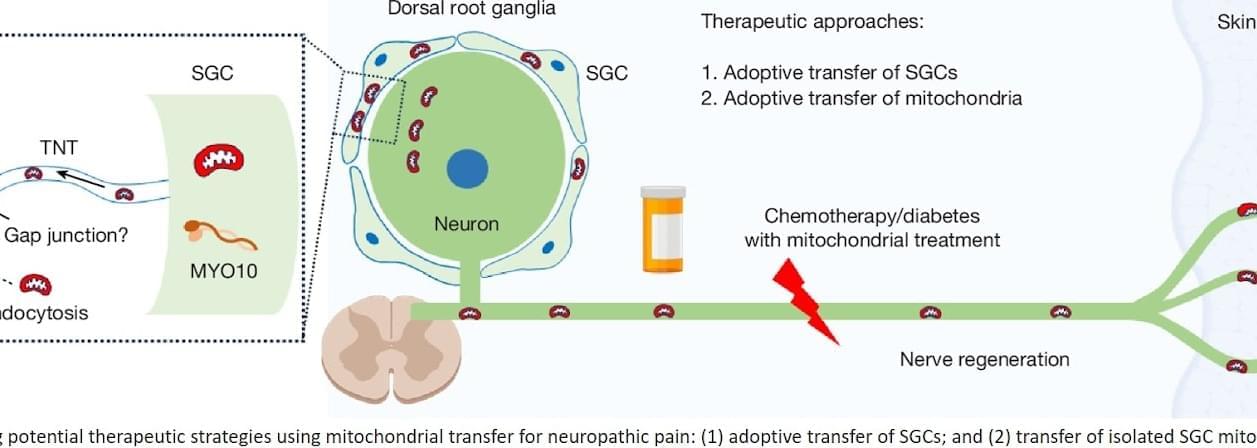

The work highlights a previously undocumented role for satellite glial cells, which appear to deliver mitochondria to sensory neurons through tiny channels called tunnelling nanotubes.

When this mitochondrial handoff is disrupted, nerve fibers begin to degenerate — triggering pain, tingling and numbness, often in the hands and feet, the distal ends of the nerve fibers.