Ferroptosis: a promising therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma👇

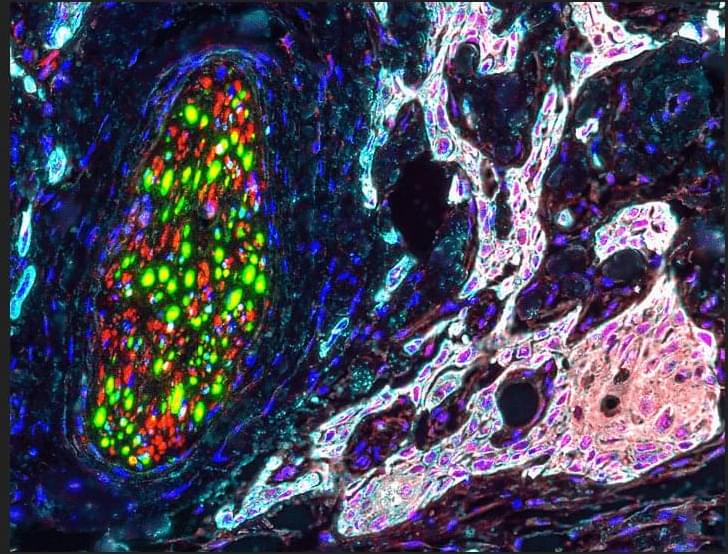

✅Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is an aggressive brain tumor characterized by rapid growth and resistance to conventional therapies. Recent research highlights ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, as a novel and promising approach for GBM treatment.

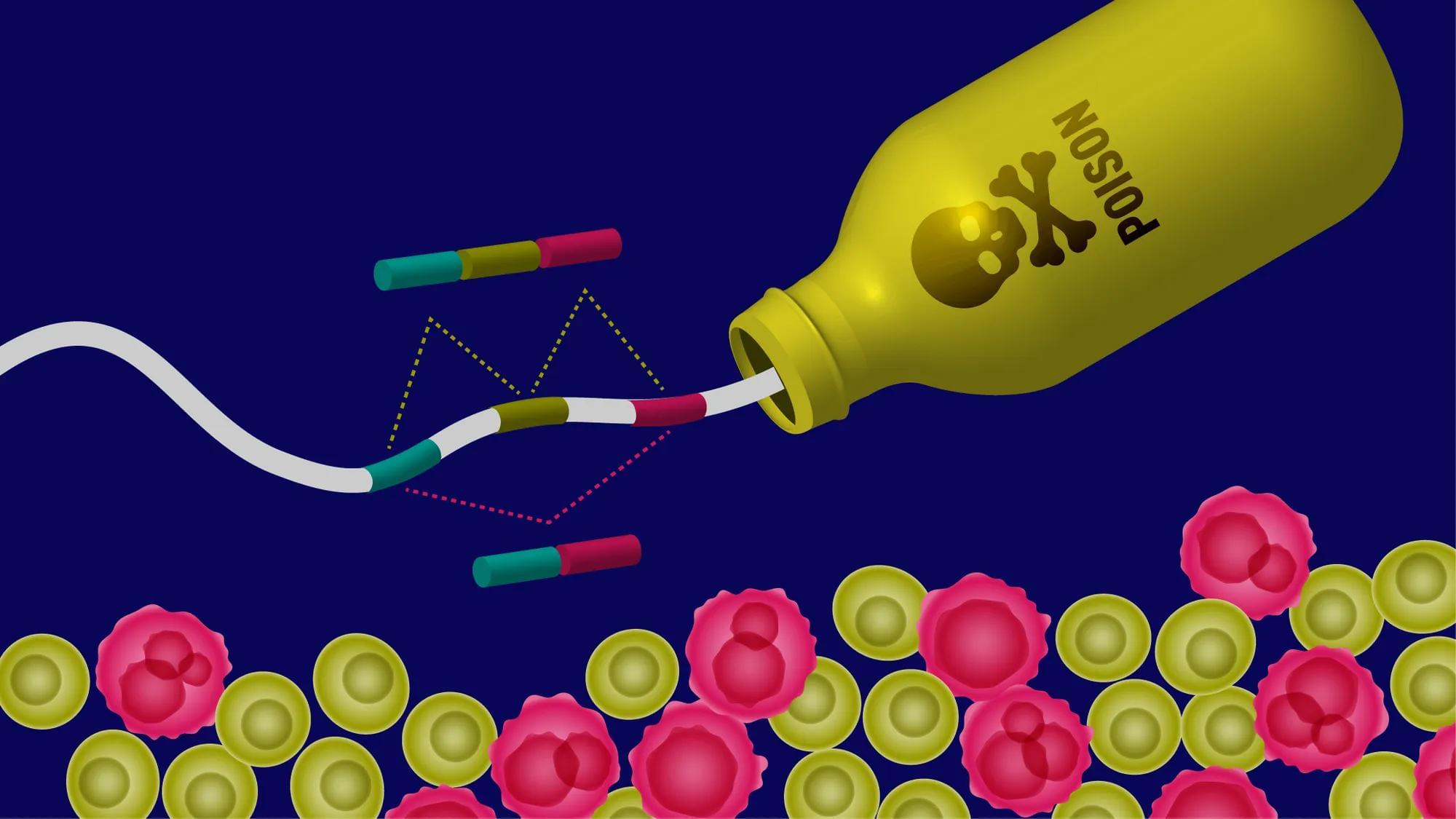

✅One key mechanism underlying ferroptosis in GBM is glutathione depletion. Inhibition of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system (xCT) limits cystine uptake, leading to reduced glutathione synthesis. As a consequence, the antioxidant enzyme GPX4 becomes inactivated, impairing the cell’s ability to detoxify lipid peroxides.

✅Lipid peroxidation is a central event in ferroptosis. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) incorporated into membrane phospholipids are highly susceptible to oxidative damage. Their conversion into peroxidized phospholipids (PL-PUFA-PE) disrupts membrane integrity and drives lethal oxidative stress.

✅Iron metabolism further amplifies ferroptotic signaling in GBM cells. Elevated intracellular iron, particularly the Fe²⁺ pool, catalyzes redox reactions that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). This iron-driven ROS production accelerates lipid peroxidation and pushes tumor cells toward ferroptotic death.

✅Collectively, glutathione depletion, GPX4 inactivation, uncontrolled lipid peroxidation, and dysregulated iron metabolism converge to induce ferroptosis. Targeting these interconnected pathways offers a potential strategy to overcome therapy resistance and selectively eliminate GBM cells.