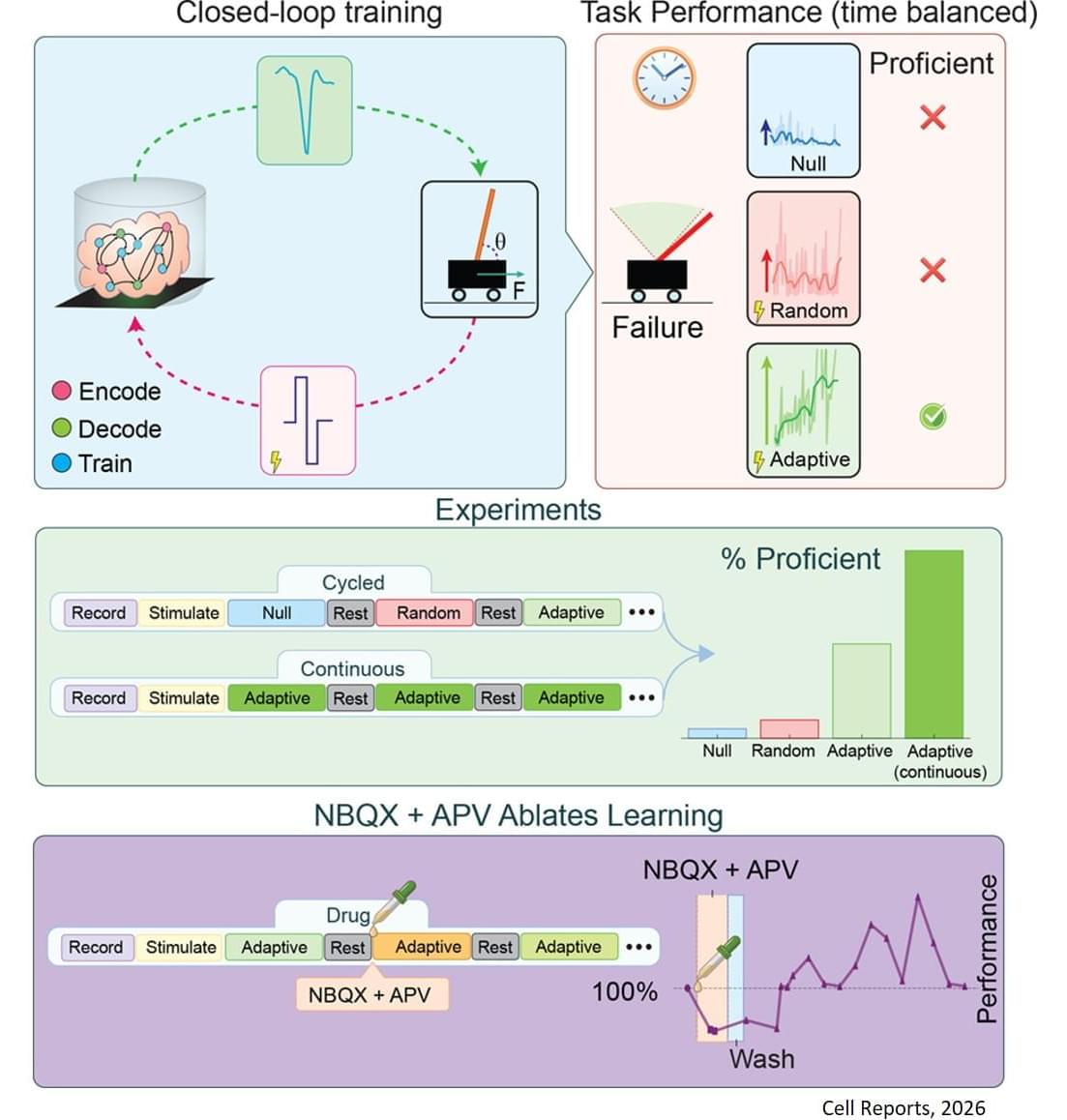

This research is the first rigorous academic demonstration of goal-directed learning in lab-grown brain organoids, and lays the foundation for adaptive organoid computation—exploring the capacity of lab-grown brain organoids to learn and solve tasks.

Using organoids derived from mouse stem cells and an electrophysiology system developed by industry partners Maxwell Biosciences, the researchers use electrical simulation to send and receive information to and from neurons. By using stronger or weaker signals, they communicate to the organoid the angle of the pole, which exists in a virtual environment, as it falls in one direction or the other. As this happens, the researchers observe as the organoid sends back signals of how to apply force to balance the pole, and they apply this force to the virtual pole.

For their pole-balancing experiments, the researchers observe as the organoid controls the pole until it drops, which is called an episode. Then, the pole is reset and a new episode begins. In essence, the organoid plays a video game in which the goal is to balance the pole upright for as long as possible.

The researchers observe the organoid’s progress in five-episode increments. If the organoid keeps the pole upright for longer on average in the past five episodes as compared to the past 20, it receives no training signal since it has been improving. If it does not improve the average time it keeps the pole upright, it receives a training signal.

Training feedback is not given to the organoid while it is balancing the pole—only at the end of an episode. An AI algorithm called reinforcement learning is used to select which neurons within the organoid get the training signal.

The results of this study prove that the reinforcement learning algorithm can guide the brain organoids toward improved performance at the cart-pole task—meaning organoids can learn to balance the pole for longer periods of time.

The researchers adopted a rigorous framework for success to make sure they were observing true improvement, and not just random success, including a threshold for the minimum time an organoid needs to balance the pole to “win” the game.