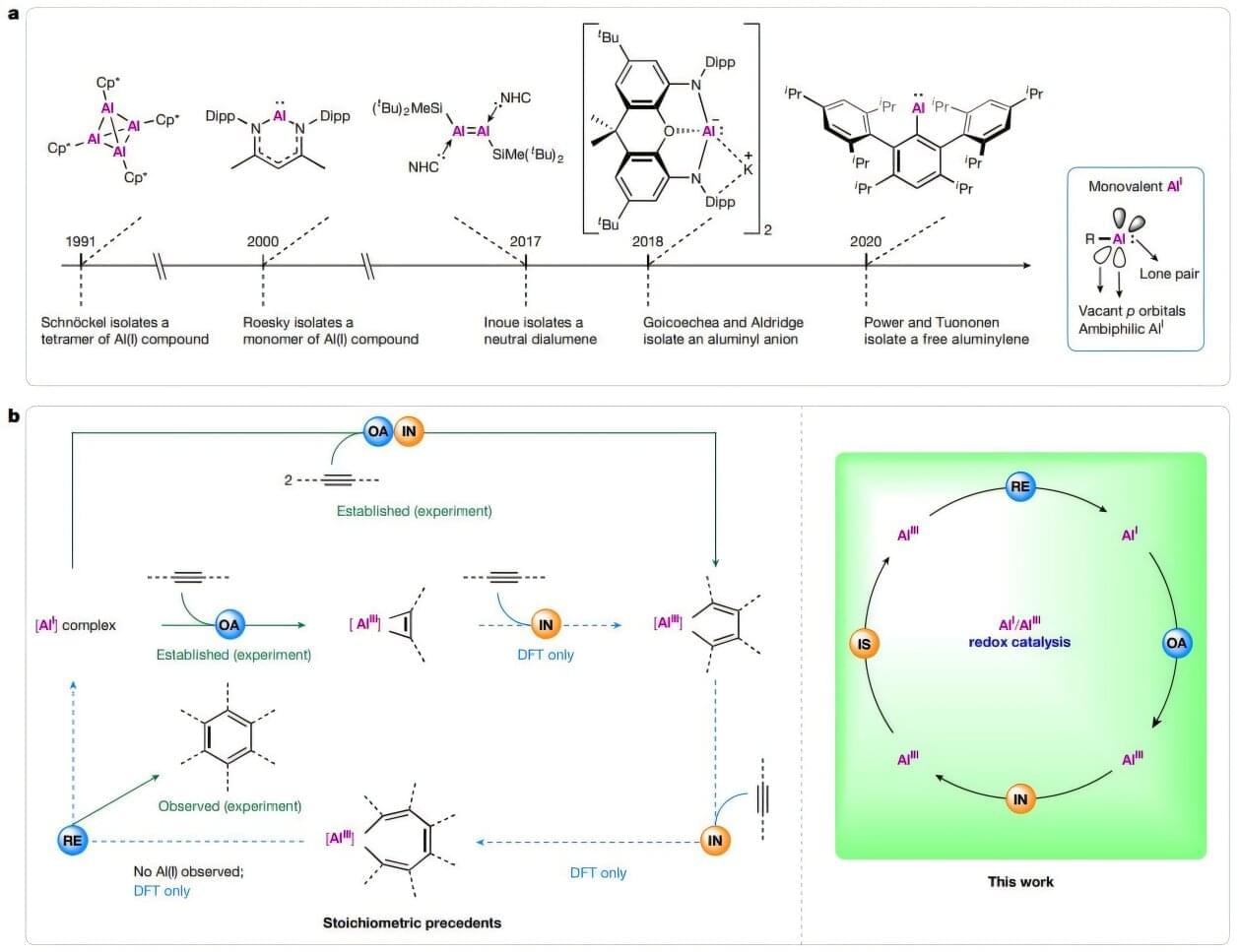

Aluminum’s journey has been remarkable, going from being more expensive than gold to one of the most widely used materials, from beverage cans to window frames and car parts. Scientists from the Southern University of Science and Technology have added a new feather in aluminum’s cap by expanding its use beyond the metallic form. They created a new aluminum-based redox catalyst —carbazolylaluminylene—that can flip back and forth between two oxidation states: Al(I) and Al(III). This catalyst drove chemical transformations long considered exclusive to transition metals.

This unique feature allowed the team to carry out selective aromatic reactions that bring together three separate alkyne molecules and assemble them into a single benzene ring, resulting in a wide range of benzene derivatives. Carbazolylaluminylene also stood out for its remarkable durability, completing up to 2,290 reaction cycles without losing any catalytic activity. The findings are published in Nature.