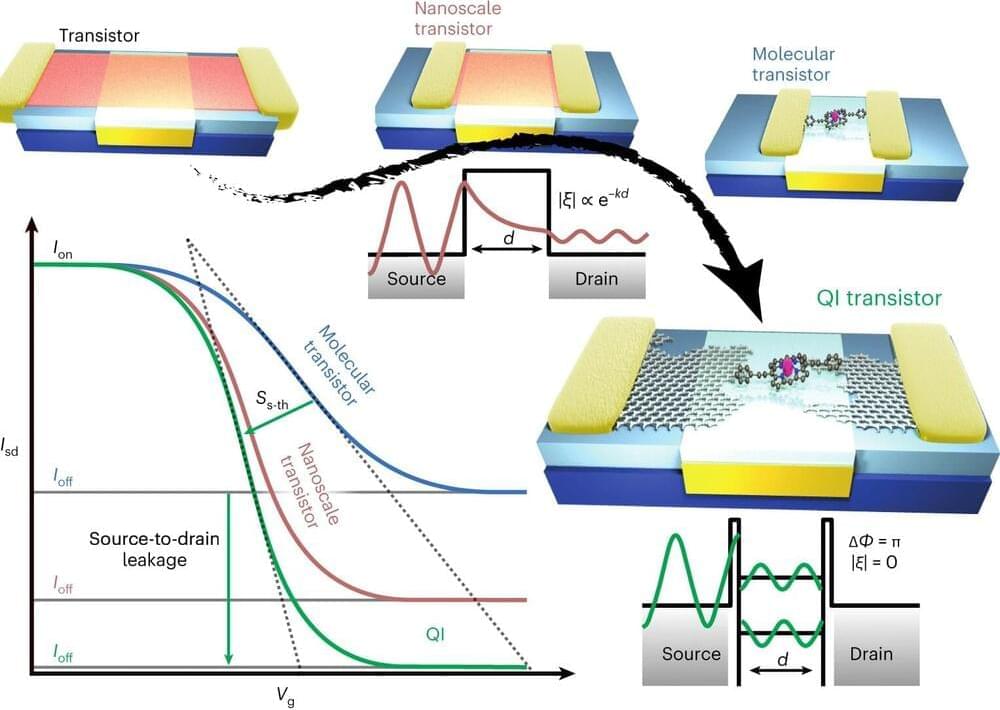

As transistors get smaller, they become increasingly inefficient and susceptible to errors, as electrons can leak through the device even when it is supposed to be switched off, by a process known as quantum tunneling. Researchers are exploring new types of switching mechanisms that can be used with different materials to remove this effect.

In the nanoscale structures that Professor Jan Mol, Dr. James Thomas, and their group study at Queen Mary’s School of Physical and Chemical Sciences, quantum mechanical effects dominate, and electrons behave as waves rather than particles. Taking advantage of these quantum effects, the researchers built a new transistor.

The transistor’s conductive channel is a single zinc porphyrin, a molecule that can conduct electricity. The porphyrin is sandwiched between two graphene electrodes, and when a voltage is applied to the electrodes, electron flow through the molecule can be controlled using quantum interference.