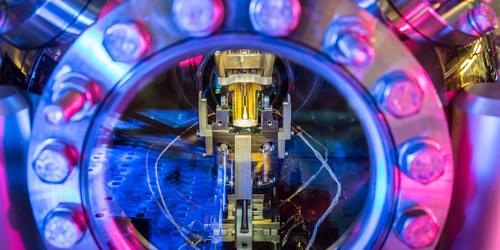

PRESS RELEASE — The full power of next-generation quantum computing could soon be harnessed by millions of individuals and companies, thanks to a breakthrough by scientists at Oxford University Physics guaranteeing security and privacy. This advance promises to unlock the transformative potential of cloud-based quantum computing and is detailed in a new study published in the influential U.S. scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

Quantum computing is developing rapidly, paving the way for new applications which could transform services in many areas like healthcare and financial services. It works in a fundamentally different way to conventional computing and is potentially far more powerful. However, it currently requires controlled conditions to remain stable and there are concerns around data authenticity and the effectiveness of current security and encryption systems.

Several leading providers of cloud-based services, like Google, Amazon, and IBM, already separately offer some elements of quantum computing. Safeguarding the privacy and security of customer data is a vital precursor to scaling up and expending its use, and for the development of new applications as the technology advances. The new study by researchers at Oxford University Physics addresses these challenges.