Up for discussion in the Guardian tech newsletter: Scandalous revelations in An Ugly Truth … the relentless march of the silicon transistor … and the dangers of link smut.

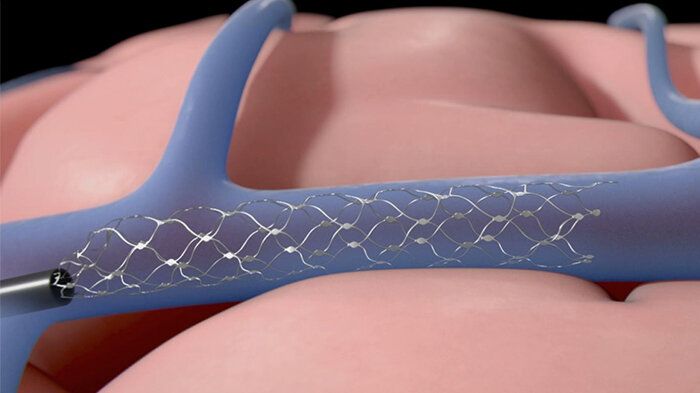

A company that makes an implantable brain-computer interface (BCI) has been given the go-ahead by the Food and Drug Administration to run a clinical trial with human patients. Synchron plans to start an early feasibility study of its Stentrode implant later this year at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York with six subjects. The company said it will assess the device’s “safety and efficacy in patients with severe paralysis.” https://www.engadget.com/fda-brain-computer-interface-clinic…ml?src=rss

A company that makes an implantable has been given the go-ahead by the Food and Drug Administration to run a clinical trial with human patients. Synchron plans to start an early feasibility study of its Stentrode implant later this year at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York with six subjects. The company said it will assess the device’s “safety and efficacy in patients with severe paralysis.”

Synchron received the FDA’s green light ahead of competitors like Elon Musk’s. Before such companies can sell BCIs commercially in the US, they need to prove that the devices work and are safe. The FDA will provide guidance for trials of BCI devices for patients with paralysis or amputation during a webinar on Thursday.

Another clinical trial of Stentrode is underway in Australia. Four patients have received the implant, which is being used “for data transfer from motor cortex to control digital devices,” Synchron said. According to data published in the Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery, two of the patients were able to control their computer with their thoughts. They completed work-related tasks, sent text messages and emails and did online banking and shopping.

Synchron has beat rival Neuralink to human trials of its “implantable brain computer interface.”

The chip will be studied in six patients later this year as a possible aid for paralyzed people.

Elon Musk previously used Neuralink’s chip in a monkey, which then played video games with its mind.

Synchron beat out rival Neuralink, led by Elon Musk, to get the FDA go-ahead for human trials of a chip implant that makes a brain-computer interface.

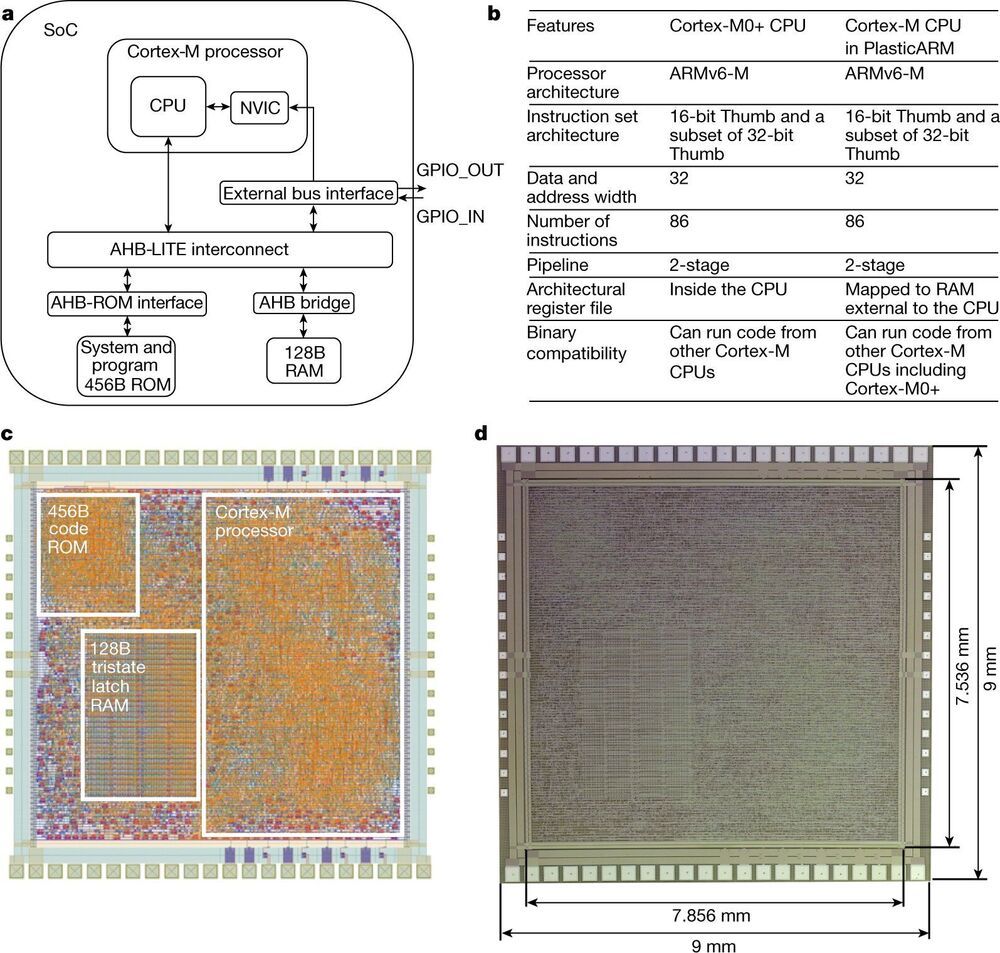

A team of researchers at ARM Inc., has developed a 32-bit microprocessor on a flexible base which the company claims could pave the way to fully flexible smart integrated systems. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the group describes how they used metal−oxide thin-film transistors along with a type of plastic to create their chip and outline ways they believe it could be used.

Microprocessors power a wide range of products, but what they all have in common is their stiffness. Almost all of them are made using silicon wafers, which means that they have to be hard and flat. This inability to bend, the researchers with this new effort contend, is what is preventing the development of products such as smart clothes, smart labels on foods, packaging and even paper products. To meet that need, the team has created what they describe as the PlasticARM—a RISC-based 32-bit microprocessor set on a flexible base. In addition to its flexibility, the new technique allows for printing a microprocessor onto many types of materials, all at low cost.

To create their bendy microprocessor, the researchers teamed with a group at PragmatIC Semiconductor to create a bendable version of the Cortex M0+ microprocessor, which was chosen for its simplicity and small size. To make their chip, (which includes ROM, RAM and interconnections) the team used amorphous silicon fabricated (in the form of metal-oxide thin-film transistors) onto flexible polymers.

Thrilled to see Paradromics’ $20M fund raise lead by the talented Dr. Amy Kruse! Paradromics is building a brain computer interface supported by DARPA’s Biologi… See More.

The investment demonstrates confidence in Paradromics as a well-positioned player in the $200 billion BCI therapy market. Last year, Paradromics successfully completed testing of its platform, demonstrating the largest ever electrical recording of cortical activity that exceeded more than 30000 electrode channels in sheep cortex. This recording allowed researchers to observe the brain activity of sheep in response to sound stimuli with high fidelity.

“We are combining the best of neural science and medical device engineering to create a robust and reliable platform for new clinical therapies,” said Paradromics CEO Matt Angle. “This funding round is a validation of both our technology and strategic vision in leading this important developing market.”

The current funding round follows $10M in early stage private funding as well as $15M of public funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Defense (DARPA).

After controlling for factors such as age, sex, handedness, first language, education level, and other variables, the researchers found that those who had contracted COVID-19 tended to underperform on the intelligence test compared to those who had not contracted the virus. The greatest deficits were observed on tasks requiring reasoning, planning and problem solving, which is in line “with reports of long-COVID, where ‘brain fog,’ trouble concentrating and difficulty finding the correct words are common,” the researchers said.

People who have recovered from COVID-19 tend to score significantly lower on an intelligence test compared to those who have not contracted the virus, according to new research published in The Lancet journal EClinicalMedicine. The findings suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 can produce substantial reductions in cognitive ability, especially among those with more severe illness.

“By coincidence, the pandemic escalated in the United Kingdom in the middle of when I was collecting cognitive and mental health data at very large scale as part of the BBC2 Horizon collaboration the Great British Intelligence Test,” said lead researcher Adam Hampshire (@HampshireHub), an associate professor in the Computational, Cognitive and Clinical Neuroimaging Laboratory at Imperial College London.

“The test comprised a set of tasks designed to measure different dimensions of cognitive ability that had been designed for application in both citizen science and clinical research. A number of my colleagues contacted me in parallel to point out that this provided an opportunity to gather important data on how the pandemic and COVID-19 illness were affecting mental health and cognition.”

Arm thinks those kinds of applications may not be far away, though. In a paper published last week in Nature, researchers from the company detailed a 32-bit microprocessor built directly onto a plastic substrate that promises to be both flexible and dramatically cheaper than today’s chips.

“We envisage that PlasticARM will pioneer the development of low-cost, fully flexible smart integrated systems to enable an ‘internet of everything’ consisting of the integration of more than a trillion inanimate objects over the next decade into the digital world,” they wrote.

Flexible electronics aren’t exactly new, and sensors, batteries, LEDs, antennae, and many other simpler components have all been demonstrated before. But a practical microprocessor that can carry out meaningful computations has been elusive thanks to the large number of transistors required, say the researchers.

More TAME! The first part of this has a lot of result data.

Foresight Biotech & Health Extension Meeting sponsored by 100 Plus Capital.

2021 program & apply to join: https://foresight.org/biotech-health-extension-program/

Nir Barzilai, Albert Einstein School of Medicine.

TAME Q&A: Lessons for Progress on Aging.

About Nir Barzilai:

Nir Barzilai, MD, is a Professor in the Department of Endocrinology Medicine and the Department of Genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He is also the Ingeborg and Ira Leon Rennert Chair of Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Dr. Barzilai is the founding director of the Institute for Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Director of the Nathan Shock Center for Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH); the center is coordinating 80 investigators and six program projects on the biology of aging. He is also the director of the Glenn Center of Excellence in the Biology of Human Aging. He is a chaired professor of medicine and of genetics and a member of the Diabetes Research Center and the divisions of endocrinology and geriatrics. Dr. Barzilai’s interests focus on several basic mechanisms in the biology of aging, including the biological effects of nutrients on extending life and the genetic determinants of life span. His team discovered many longevity gene in humans, and they further characterized the phenotype and genotype of humans with exceptional longevity through NIH awards. He also has an NIH Merit award investigating the metabolic decline that accompanies aging and its impact on longevity. Dr. Barzilai has published more than 270 peer-reviewed papers, reviews and chapters in textbooks. Dr. Barzilai serves on several editorial boards and advisory boards of pharmaceutical and start-up companies, and is a reviewer for numerous journals. A Beeson Fellow for Aging Research, Dr. Barzilai has received many other prestigious awards, including the Senior Ellison Foundation Award, the 2010 Irving S. Wright Award of Distinction in Aging Research, the NIA–Nathan Shock Award and a merit award from the NIA for his contributions in elucidating metabolic and genetic mechanisms of aging and was the 2018 recipient of the IPSEN Longevity award. He is leading the TAME (Targeting/Taming Aging with Metformin) Trial, a multi-center study to prove the concept that multi morbidities of aging can be delayed in humans and change the FDA indications to allow for next generation interventions. He is a founder of CohBar Inc. (now public company) and Medical Advisor for Life Biosciences. He is on the board of AFAR and a founding member of the Academy for Lifespan and Healthspan. He has been featured in major papers, TV programs, and documentaries (TEDx and TEDMED) and has been consulting or presented the promise for targeting aging at The Singapore Prime Minister Office, several International Banks, The Vatican, Pepsico, Milkin Institute, The Economist and Wired Magazine. His book, Age Later: Health Span, Life Span, and the New Science of Longevity, was published by St. Martin’s Press in June of 2020.

Zoom Transcription: https://otter.ai/u/0bz5o2crLQncfxlUkctY6NVzcCg.

Russia has unveiled the Sukhoi Checkmate, a new fifth-generation fighter jet intended to supplement the Su-57 and conquer the international market.

A mockup of the aircraft was presented in a grand ceremony on the opening day of the MAKS airshow in Moscow on July 20, 2021.

“We have been working on the project for just slightly longer than one year. Such a fast development cycle was possible only with the help of advanced computer technologies and virtual testing,” Yuri Slyusar, CEO of United Aircraft Corporation (UAC), said at the event.

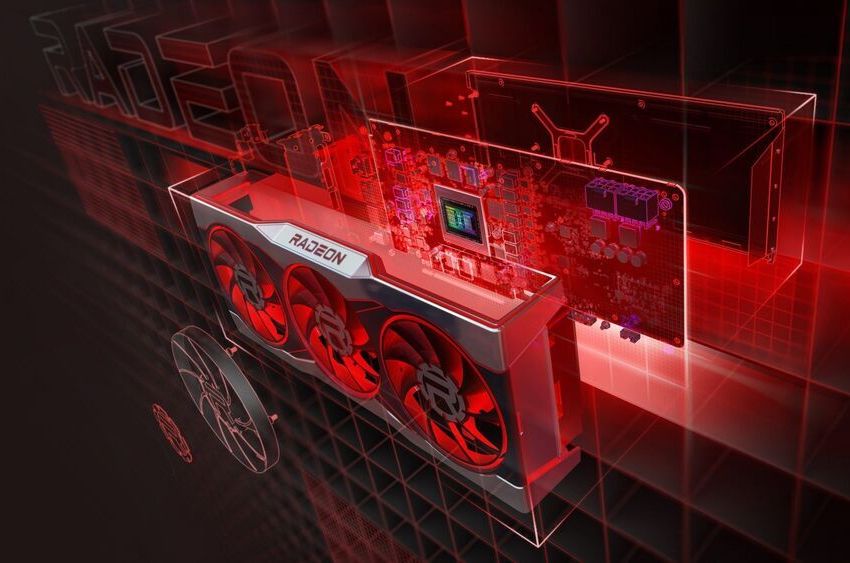

AMD’s next-generation Radeon RX 7900 XT GPU featuring the Big Navi 31 RDNA 3 GPU could feature an insane 15360 cores in 60 WGPs.

A brand new rumor regarding AMD’s next-generation and flagship RDNA 3 GPU, the Big Navi 31, which is going to power the Radeon RX 7900 XT graphics card, has been published by Beyond3D forums (via 3DCenter). The rumor suggests that AMD is dropping a very popular GPU terminology from its RDNA 3 lineup.

AMD Radeon RX 7900 XT ‘Big Navi 31’ RDNA 3 GPU To Feature Up To 60 WGPs For A Total of 15360 Cores

We are seeing a lot of rumors regarding AMD’s RDNA 3 GPUs pop up recently. Last we heard, the AMD Big Navi GPU within the RDNA 3 lineup, the Navi 31, was going to feature 240 Compute Units or 120 CUs per die for a total of 15360 cores. But Beyond3D forum member, Bondrewd, is quite confident that the era of the CU or Compute Unit is over and AMD is moving over to WGP or Work Group Processors as the main core block of its next-generation GPUs.