The secret to how steel hardens and shape-memory alloys snap into place lies in rapid, atomic-scale shifts that scientists have struggled to observe in materials. Now, Cornell researchers are revealing how these transformations unfold, particle by particle, through advanced modeling techniques.

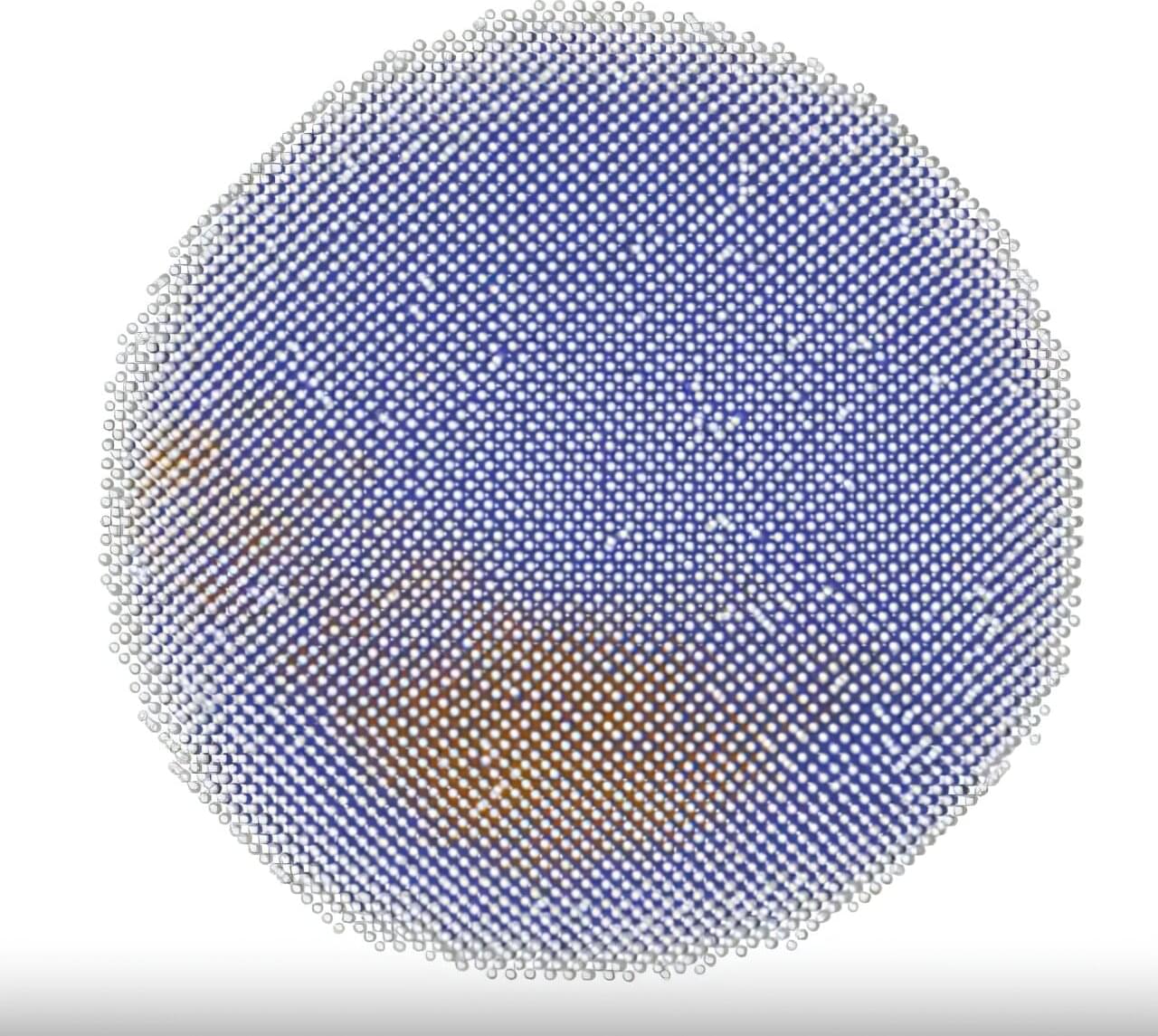

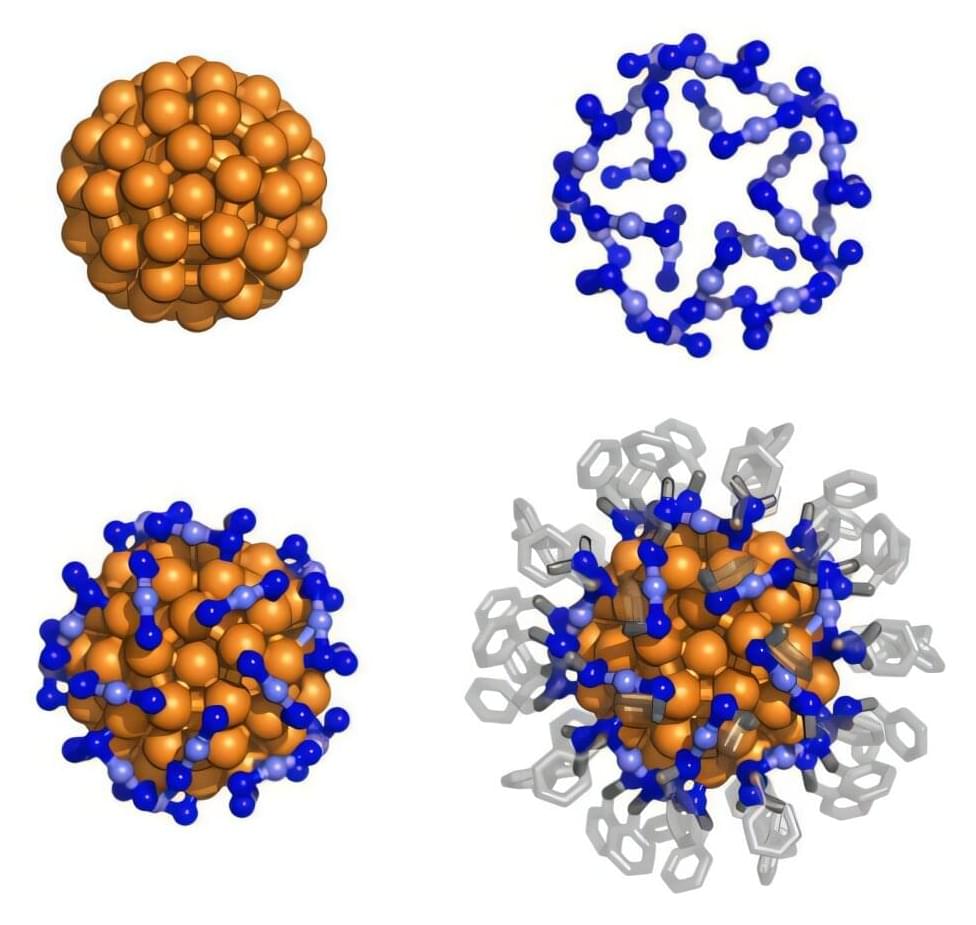

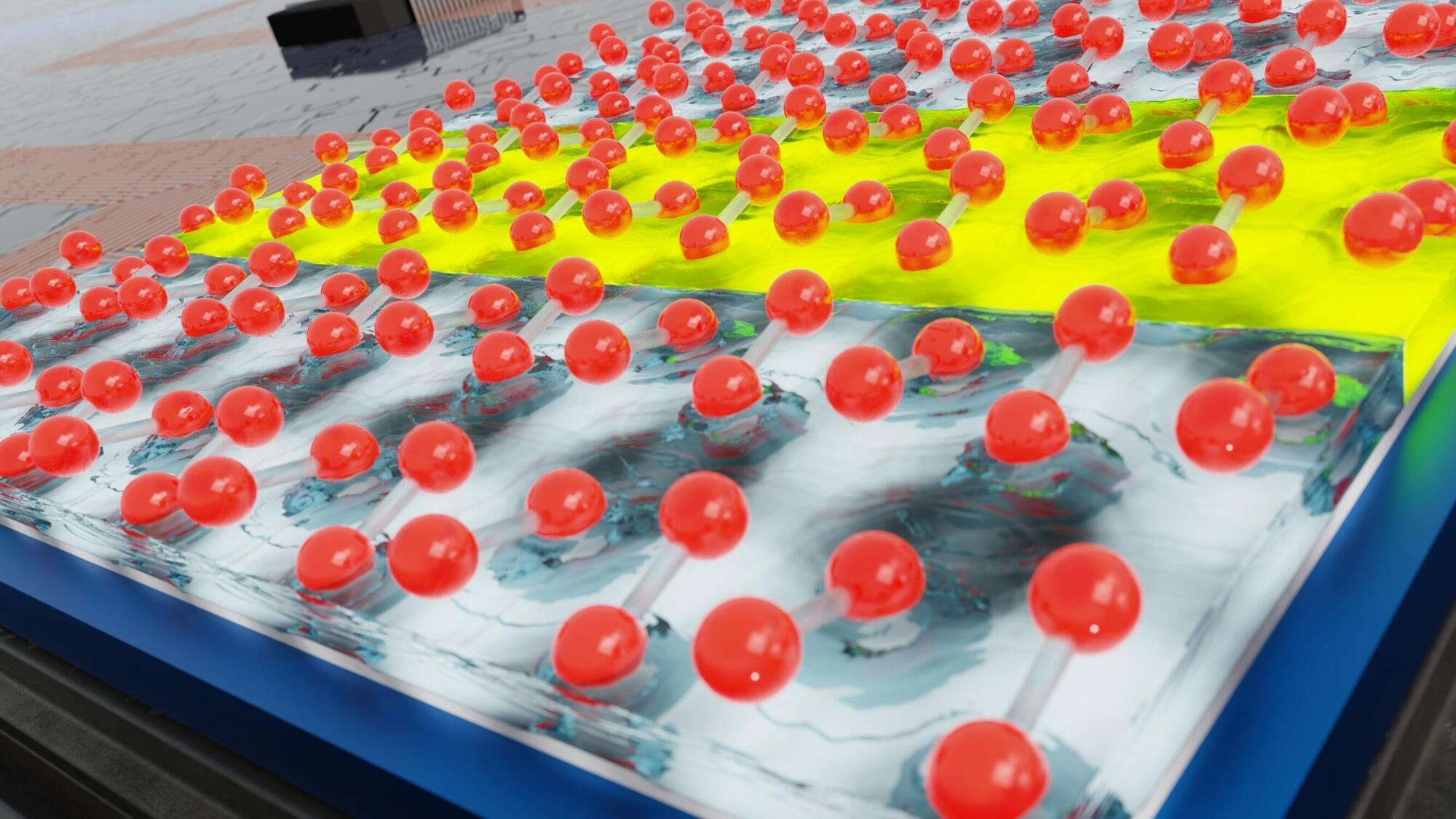

Using custom-built computer simulations, Julia Dshemuchadse, assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Cornell Engineering, and Hillary Pan, Ph.D., have visualized solid-solid phase transitions in unprecedented detail, capturing the motion of every particle in a theoretical material as its crystal structure morphs into another.

Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveal not only classical transformation mechanisms, but also entirely new ones, reshaping how scientists understand this fundamental process in materials science.