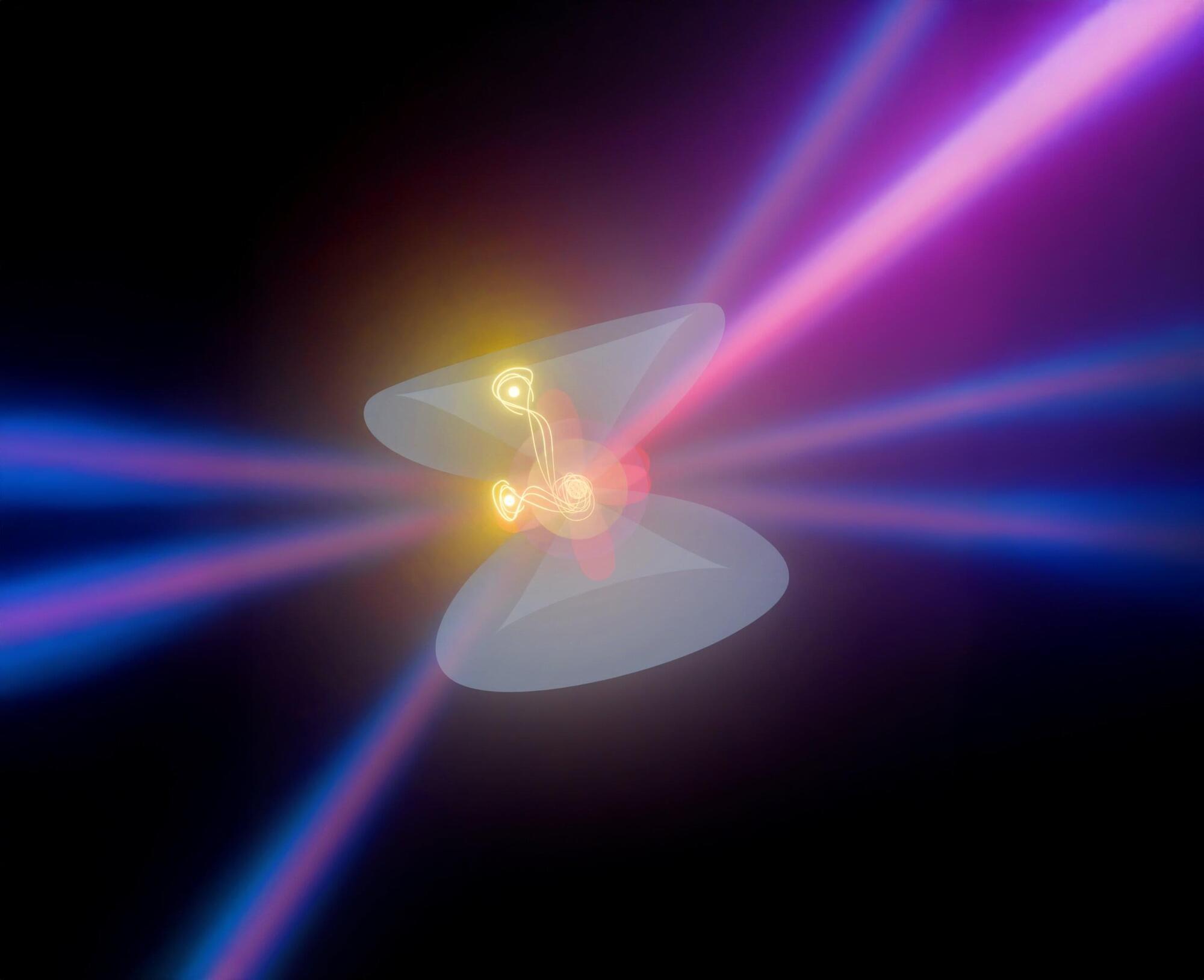

Scientists at the X-ray free-electron laser SwissFEL have realized a long-pursued experimental goal in physics: to show how electrons dance together. The technique, known as X-ray four-wave mixing, opens a new way to see how energy and information flow within atoms and molecules. In the future, it could illuminate how quantum information is stored and lost, eventually aiding the design of more error-tolerant quantum devices. The findings are reported in Nature.

Much of the behavior of matter arises not from electrons acting alone, but from the ways they influence each other. From chemical systems to advanced materials, their interactions shape how molecules rearrange, how materials conduct or insulate and how energy flows.

In many quantum technologies —not least quantum computing—information is stored in delicate patterns of these interactions, known as coherences. When these coherences are lost, information disappears—a process known as decoherence. Learning how to understand and ultimately control such fleeting states is one of the major challenges facing quantum technologies today.