New data revises our view of this unusual supernova explosion. A team of scientists used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to parse the composition of the Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant located 6,500 light-years away in the constellation Taurus. With the telescope’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) and NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera), the team gathered data that is […].

Category: cosmology – Page 141

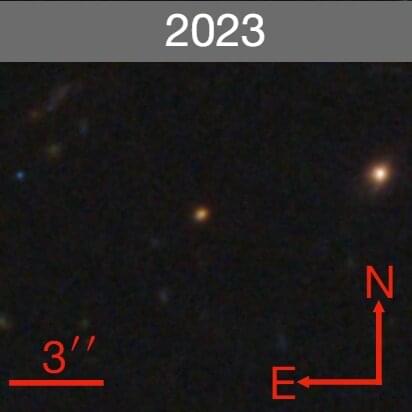

New Type Ia supernova discovered

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) have discovered a new supernova. Designated SN 2023adsy, the newfound stellar explosion is the most distant Type Ia supernova so far detected. The finding was detailed in a research paper published June 7 on the pre-print server arXiv.

Astronomers find black holes created in mergers carry information about their ancestors

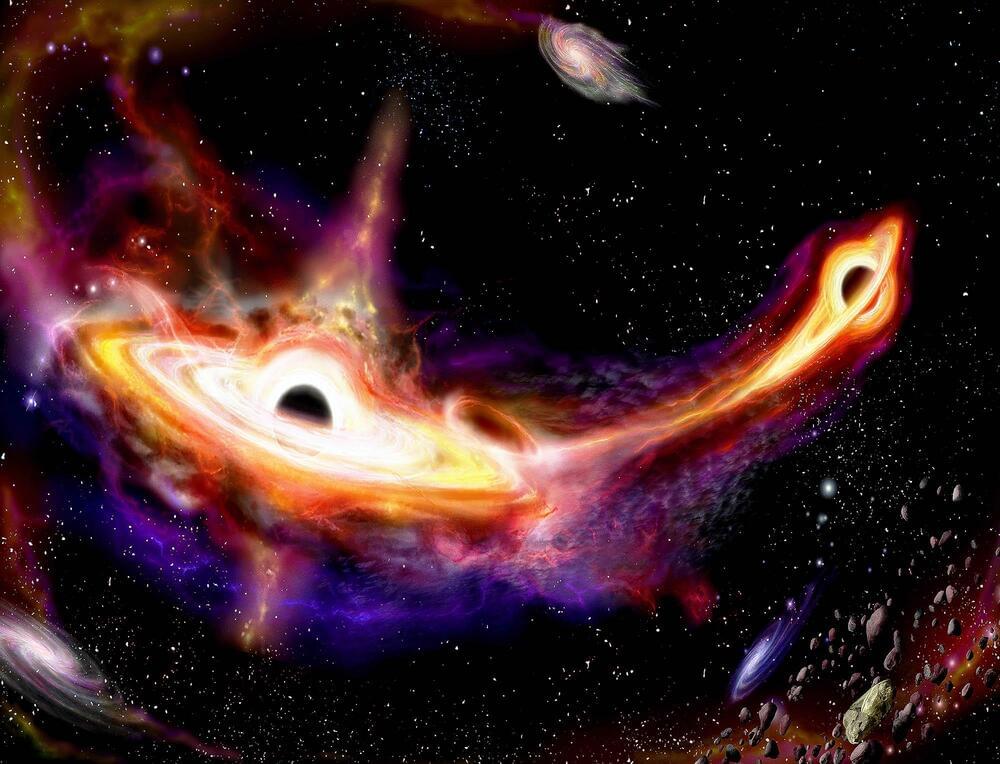

Astronomers believe that at the heart of most, if not all, galaxies sits a titanic black hole with a mass that is millions or even billions of times that of our sun. These supermassive black holes cannot be directly created through the collapse of a massive star, as is the case with stellar mass black holes with masses tens of times that of the sun, as no star is large enough to birth such a huge object.

China’s Moon Mission Could Reveal the Origins of Life on Earth

China´s Moon Mission May Reveal the Origin of Life on Earth Blog posted on Big Think, direct link on searchforlifeintheuniverse.com

NASA Releases Video of What It’s Like to Fall Into a Black Hole

“Stellar-mass black holes, which contain up to about 30 solar masses, possess much smaller event horizons and stronger tidal forces, which can rip apart approaching objects before they get to the horizon.”

The simulated black hole is designed to imitate the supermassive one at the heart of our galaxy, which has a mass over 4.3 million times that of our Sun. That is almost unfathomably large: the distant view of it you see in the visualizer is from nearly 400 million miles away.

From the point of view of the doomed camera, falling into the event horizon would take three hours. To an outside observer, however, the camera would appear to freeze just before the threshold due to immense distortions in spacetime.

Dark Energy comes from Anti-Universe, New Theory Says

Try Opera browser FOR FREE here https://opr.as/04-Opera-browser-sabinehossenfelderDark Energy is the name that astrophysicists have given to what ever acceler…

New Simulation Explains how Supermassive Black Holes Grew so Quickly

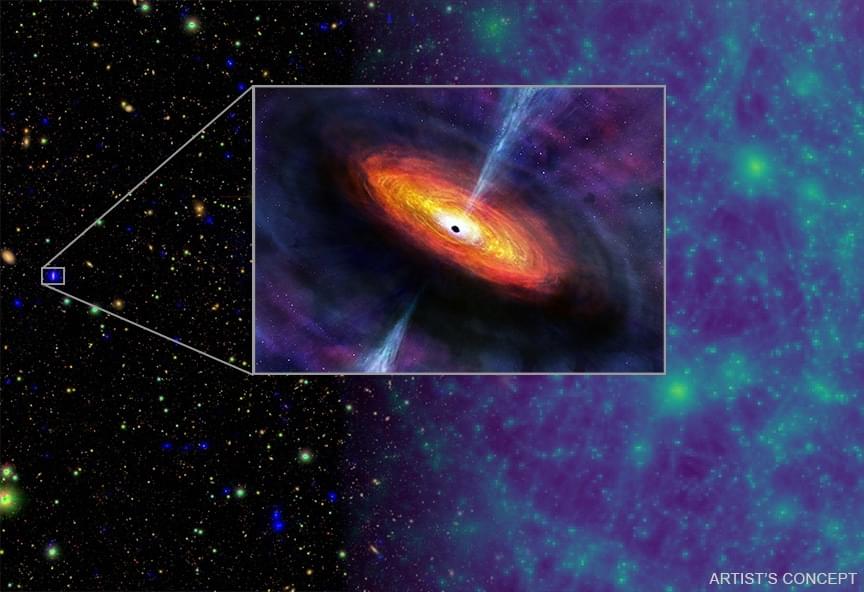

One of the main scientific objectives of next-generation observatories (like the James Webb Space Telescope) has been to observe the first galaxies in the Universe – those that existed at Cosmic Dawn. This period is when the first stars, galaxies, and black holes in our Universe formed, roughly 50 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang. By examining how these galaxies formed and evolved during the earliest cosmological periods, astronomers will have a complete picture of how the Universe has changed with time.

As addressed in previous articles, the results of Webb’s most distant observations have turned up a few surprises. In addition to revealing that galaxies formed rapidly in the early Universe, astronomers also noticed these galaxies had particularly massive supermassive black holes (SMBH) at their centers. This was particularly confounding since, according to conventional models, these galaxies and black holes didn’t have enough time to form. In a recent study, a team led by Penn State astronomers has developed a model that could explain how SMBHs grew so quickly in the early Universe.

The research team was led by W. Niel Brandt, the Eberly Family Chair Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State’s Eberly College of Science. Their research is described in two papers presented at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS224), which took place from June 9th to June 13th in Madison, Wisconsin. Their first paper, “Mapping the Growth of Supermassive Black Holes as a Function of Galaxy Stellar Mass and Redshift,” appeared on March 29th in The Astrophysical Journal, while the second is pending publication. Fan Zou, an Eberly College graduate student, was the lead author of both papers.

Nova explosion of nearby star will soon light up Earth’s skies

The vast expanse of the night sky, a canvas dotted with countless stars, is about to unveil a rare and spectacular phenomenon. Brace yourself for a stellar light show as T Coronae Borealis, a seemingly unremarkable star nestled within the constellation Corona Borealis, is on the brink of a dramatic nova explosion.

T Coronae Borealis, affectionately known as T CrB, is no ordinary star. It’s a binary system, a celestial pattern of two stars locked in a gravitational embrace.

At the heart of this cosmic process lies a white dwarf, the incredibly dense remnant of a once-mighty star. Its partner, a bloated red giant, is in the twilight years of its existence, slowly shedding its outer layers under the relentless pull of the white dwarf’s gravity.