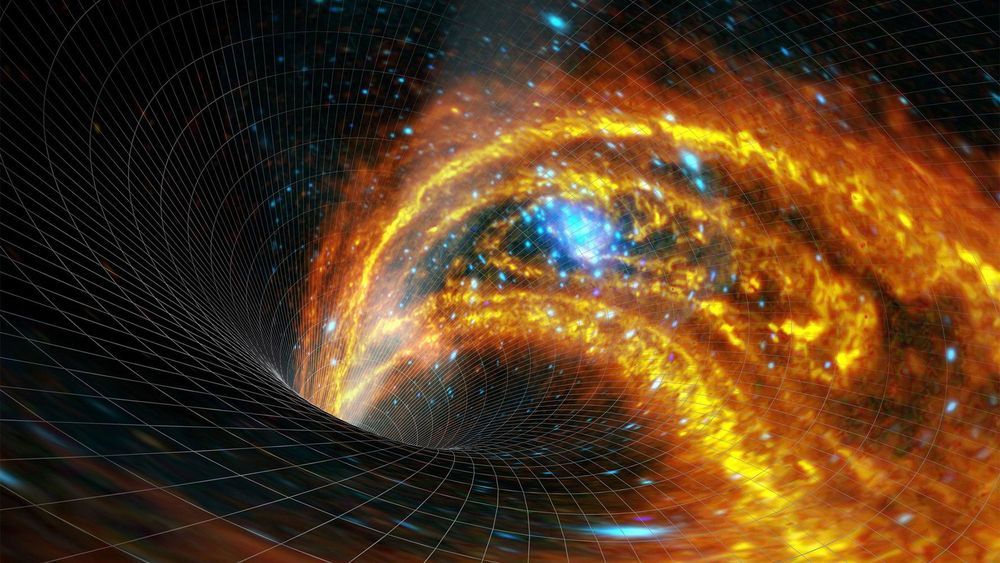

This video shows what you will see if you fall into a black hole. It is not an artistic impression, but a result of general- relativistic supercomputer simulation by prof. Andrew Hamilton.

Category: cosmology – Page 426

5 Intriguing Theories about Dark Matter

Dark matter is a hypothetical invisible mass, which is responsible for the force of gravity among galaxies and other celestial bodies. Although researchers don’t have any concrete information about this puzzling entity, they did come up with a number of intriguing theories about this enigmatic mass. Following is a list of 5 dark matter theories that are quite interesting.

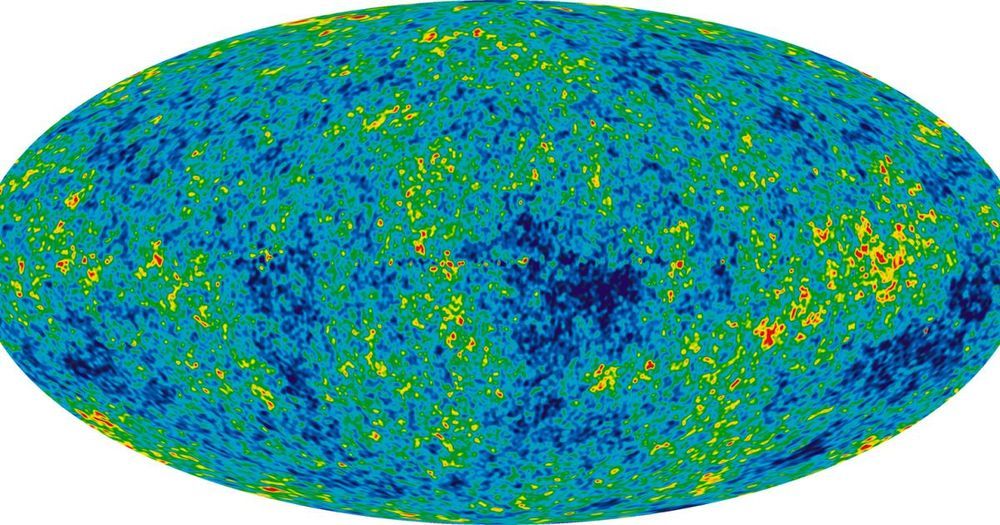

WIMPs are hypothetical particles that are thought to constitute dark matter. These heavy, electromagnetically neutral subatomic particles are hypothesized to make up 22% of the entire universe. They are thought to be heavy and slow-moving because if the dark matter particles were light and fast, they would not have clumped together in the density fluctuations from which galaxies and clusters of galaxies are formed. The precise nature of these particles is currently unknown and they do not abide by the laws of the Standard Model of Particle Physics.

Axions are believed to be neutral, slow-moving particles that are a billion times lighter than electrons. They rarely interact with light and this behavior has urged scientists to believe that Axion could be a building block of the dark matter. An attempt to detect these particles was made in April 2018 by the physicists from the University of Washington. The main idea of this theory suggests that if axions are constantly dashing towards Earth, powerful magnets may be able to convert some of the axions into microwave photons, which are easier to detect. Their work is commonly known as the Axion Dark Matter Experiment (ADMX) and this theory has not enjoyed much success, since then.

A quantum simulation of Unruh radiation

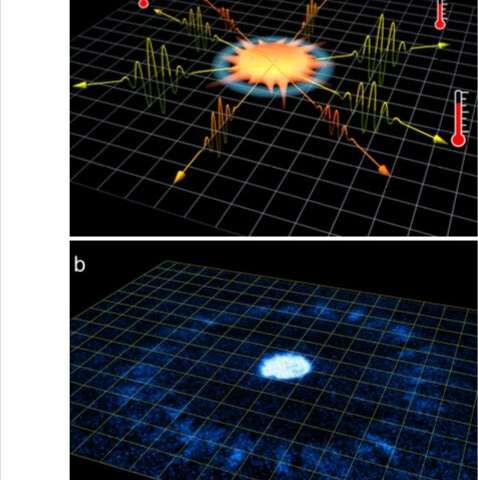

Researchers at the University of Chicago (UChicago) have recently reported an experimental observation of a matter field with thermal fluctuations that is in accordance with Unruh’s radiation predictions. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, could open up new possibilities for research exploring the dynamics of quantum systems in a curved spacetime.

“Our team at UChicago has been investigating a new quantum phenomena called Bose fireworks that we discovered two years ago,” Cheng Chin, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “Our paper reports its hidden connection to a gravitational phenomenon called Unruh radiation.”

The Unruh effect, or Unruh radiation, is closely connected to Hawking radiation. In 1974, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking predicted that the strong gravitational force near black holes leads to the emission of a thermal radiation of particles, which resembles the heat wave emitted by an oven. This phenomenon remains speculative with no direct experimental confirmation.

Spacetime Geometry near Rotating Black Holes Acts Like Quantum Computer, Physicist Says

According to a theoretical paper published in the Annals of Physics, by Dr. Ovidiu Racorean from the General Direction of Information Technology in Bucharest, Romania, the geometry of spacetime around a rapidly spinning black hole (Kerr black hole) behaves like a quantum computer, and it can encode photons with quantum messages.

Black Hole Propulsion as Technosignature

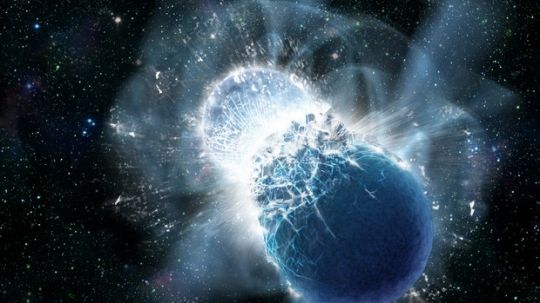

When he was considering white dwarfs and neutron stars in the context of what he called ‘gravitational machines,’ Freeman Dyson became intrigued by the fate of a neutron star binary. He calculated in his paper of the same name (citation below) that gradual loss of energy through gravitational radiation would bring the two neutron stars together, creating a gravitational wave event of the sort that has since been observed. Long before LIGO, Dyson was talking about gravitational wave detection instruments that could track the ‘gravitational flash.’

Image: Artist conception of the moment two neutron stars collide. Credit: LIGO / Caltech / MIT.

Using black holes to conquer space: The halo drive

The idea of traveling to another star system has been the dream of people long before the first rockets and astronauts were sent to space. But despite all the progress we have made since the beginning of the Space Age, interstellar travel remains just that – a dream. While theoretical concepts have been proposed, the issues of cost, travel time and fuel remain highly problematic.

A lot of hopes currently hinge on the use of directed energy and lightsails to push tiny spacecraft to relativistic speeds. But what if there was a way to make larger spacecraft fast enough to conduct interstellar voyages? According to Prof. David Kipping, the leader of Columbia University’s Cool Worlds lab, future spacecraft could rely on a halo drive, which uses the gravitational force of a black hole to reach incredible speeds.

Prof. Kipping described this concept in a recent study that appeared online (the preprint is also available on the Cool Worlds website). In it, Kipping addressed one of the greatest challenges posed by space exploration, which is the sheer amount of time and energy it would take to send a spacecraft on a mission to explore beyond our solar system.