Nissan says solid state batteries will double intensity of lithium batteries and cost less, and can also be used as energy storage.

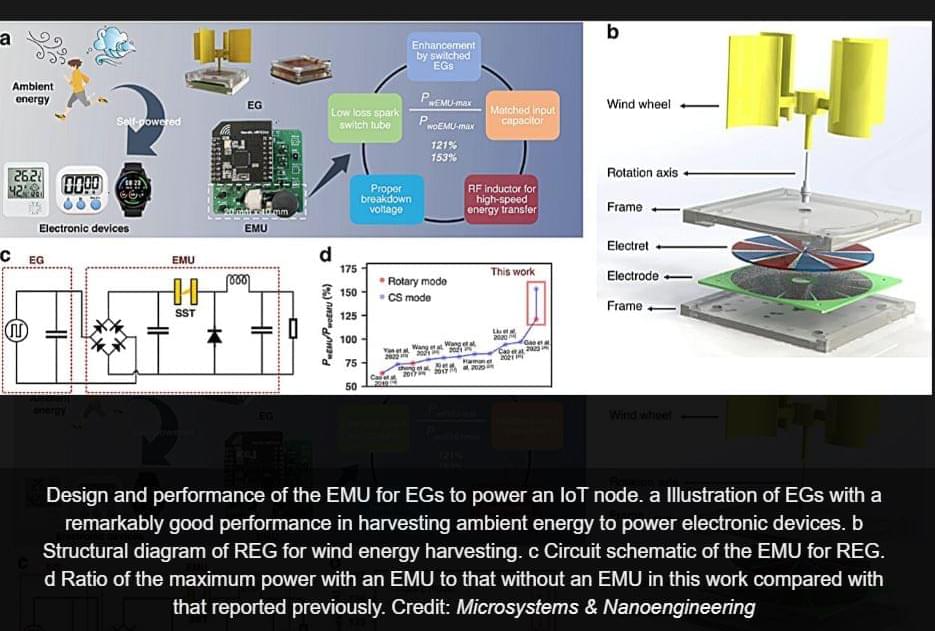

Researchers have developed a high-performance energy management unit (EMU) that significantly boosts the efficiency of electrostatic generators for Internet of Things (IoT) applications. This breakthrough addresses the challenge of high impedance mismatch between electrostatic generators and electronic devices, unlocking new possibilities for ambient energy harvesting.

Electrostatic generators have emerged as a promising solution for powering low-power devices in Internet of Things (IoT) networks, utilizing energy from environmental sources such as wind and human motion. Despite their potential, the effectiveness of these generators has been hampered by an impedance mismatch when connected to electronic devices, leading to low energy utilization efficiency.

A study published in the journal Microsystems & Nanoengineering introduces an efficient energy management unit (EMU) designed to significantly boost the power efficiency of electrostatic generators for IoT devices. This innovation addresses the longstanding challenge of impedance mismatch and propels forward the potential for using environmental energy harvesting within the IoT domain.

I found this on NewsBreak.

Researchers in China have reportedly developed a new technology similar to hydropanels for harvesting water out of thin air that is powered by energy from the sun. The device could be especially useful in dry, arid areas where water — but not sunlight — is hard to come by.

The findings from the research team from Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China were published in the scientific journal Applied Physics Reviews.

“This atmospheric water harvesting technology can be used to increase the daily water supply needs, such as household drinking water, industrial water, and water for personal hygiene,” said Ruzhu Wang, one of the study’s authors.

In a major clean energy benchmark, wind, solar, and hydro exceeded 100% of demand on California’s main grid for 30 of the past 38 days.

Stanford University professor of civil and environmental engineering Mark Z. Jacobson has been tracking California’s renewables performance, and he shares his findings on Twitter (X) when the state breaks records. Yesterday he posted:

Jacobson notes that supply exceeds demand for “0.25−6 h per day,” and that’s an important fact. The continuity lies not in renewables running the grid for the entire day but in the fact that it’s happening on a consistent daily basis, which has never been achieved before.

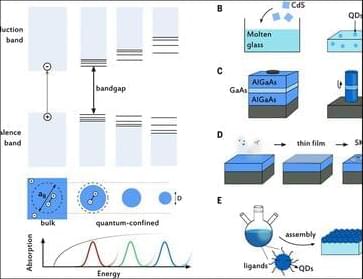

Quantum #dots feature widely tunable and distinctive optical, electrical, chemical, and physical properties. They span energy #harvesting, #ILLUMINATION, #displays, #cameras, and more.

Read more on #WorldQuantumDay: #Sciencereview.

Semiconductor quantum dots: Technological progress and future challenges.

A small town in central Utah is set to be the home of a new underground “battery” that will store hydrogen as a clean energy source.

According to The New York Times, developers are creating two caverns as deep as the Empire State Building is tall from a geological salt formation near Delta, Utah. These caverns, which are expected to be complete next year, will be able to store hydrogen gas.

The hydrogen will be produced nearby through a process called electrolysis. This will be done using excess solar and wind power in spring and fall, when demand for energy is low. Then it can be stored until peak energy demand hits in the summer — at that time, it would be burned at a power plant as a blend of hydrogen and natural gas.

Unveiling Chiral Interface States

The chiral interface state is a conducting channel that allows electrons to travel in only one direction, preventing them from being scattered backward and causing energy-wasting electrical resistance. Researchers are working to better understand the properties of chiral interface states in real materials but visualizing their spatial characteristics has proved to be exceptionally difficult.

But now, for the first time, atomic-resolution images captured by a research team at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley have directly visualized a chiral interface state. The researchers also demonstrated on-demand creation of these resistance-free conducting channels in a 2D insulator.

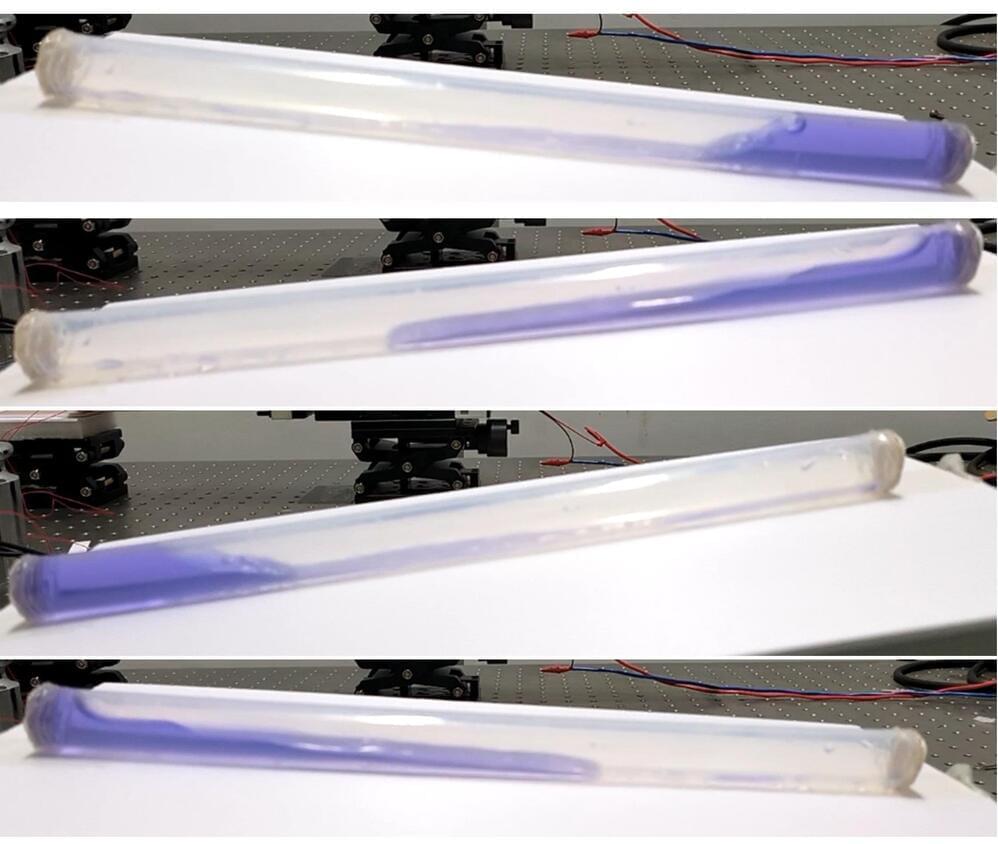

As any surfer will tell you, waves pack a powerful punch. We’re now making strides toward harnessing the ocean’s relentless movements for energy, thanks to advancements in “blue energy” technology. In a study published in ACS Energy Letters, researchers discovered that by moving the electrode from the middle to the end of a liquid-filled tube—where the water’s impact is strongest—they significantly boosted the efficiency of wave energy collection.

The tube-shaped wave-energy harvesting device improved upon by the researchers is called a liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG). The TENG converts mechanical energy into electricity as water sloshes back and forth against the inside of the tube. One reason these devices aren’t yet practical for large-scale applications is their low energy output. Guozhang Dai, Kai Yin, Junliang Yan, and colleagues aimed to increase a liquid-solid TENG’s energy harvesting ability by optimizing the location of the energy-collecting electrode.