With four electric motors each pumping out 240kW of power, BYD’s new Yangwang U7 is a powerful large sedan.

Twitter files author Michael Shellenberger weighs in on recent leaked NIH emails. #Fauci #covidorigins.

About Rising:

Rising is a weekday morning show with bipartisan hosts that breaks the mold of morning TV by taking viewers inside the halls of Washington power like never before. The show leans into the day’s political cycle with cutting edge analysis from DC insiders who can predict what is going to happen. It also sets the day’s political agenda by breaking exclusive news with a team of scoop-driven reporters and demanding answers during interviews with the country’s most important political newsmakers.

Follow Rising on social media:

Website: Hill. TV

Facebook: facebook.com/HillTVLive/

Instagram: @HillTVLive.

A stable, reactive, and cost-effective ruthenium catalyst for sustainable hydrogen production through proton exchange membrane water electrolysis.

Sustainable electrolysis for green hydrogen production is challenging, primarily due to the absence of efficient, low-cost, and stable catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic solutions. A team of researchers has now developed a ruthenium catalyst by doping it with zinc, resulting in enhanced stability and reactivity compared to its commercial version. The proposed strategy can revolutionize hydrogen production by paving the way for next generation electrocatalysts that contribute to clean energy technologies.

Electrolysis and Catalyst Challenges.

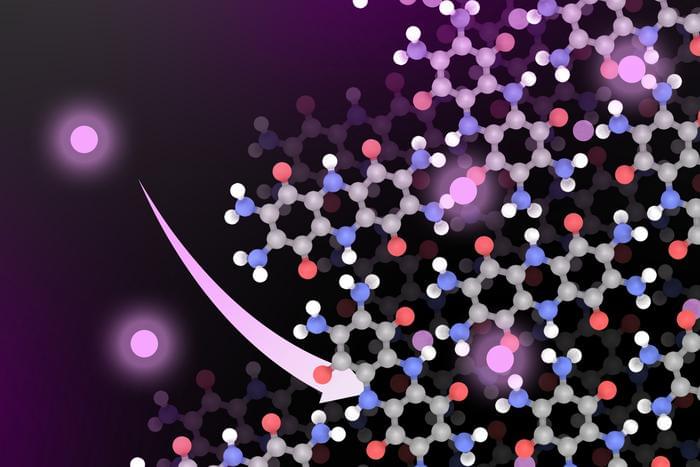

Researchers have found that treating seeds with ethylene gas increases both their growth and stress tolerance. This discovery, involving enhanced photosynthesis and carbohydrate production in plants, offers a potential breakthrough in improving crop yields and resilience against environmental stressors.

Just like any other organism, plants can get stressed. Usually, it’s conditions like heat and drought that lead to this stress, and when they’re stressed, plants might not grow as large or produce as much. This can be a problem for farmers, so many scientists have tried genetically modifying plants to be more resilient.

However plants modified for higher crop yields tend to have a lower stress tolerance because they put more energy into growth than into protection against stresses. Similarly, improving the ability of plants to survive stress often results in plants that produce less because they put more energy into protection than into growth. This conundrum makes it difficult to improve crop production.

North Korea claimed to have launched a new solid-fuel, intermediate-range missile with a hypersonic warhead, aiming to test its reliability and maneuverability. The missile, designed to strike U.S. military bases in Guam and Japan, flew approximately 620 miles before landing between the Korean Peninsula and Japan. The test follows a previous claim of successfully testing […] The post North Korea Unveils New Missile Designed for US Mainland…

Researchers develop artificial ‘power plants’ in the form of tiny leaf-shapes to harness energy from the wind and rain.

“I think this material could have a big impact because it works really well,” said Dr. Mircea Dincă. “It is already competitive with incumbent technologies, and it can save a lot of the cost and pain and environmental issues related to mining the metals that currently go into batteries.”

Electric vehicles (EVs) have become a household name in the last few years with several companies fighting to compete in the everchanging EV landscape as EV technology continues to improve in cost, efficiency, and the materials used to manufacture the batteries responsible for sustaining this clean energy revolution. While EV batteries have traditionally used cobalt for their battery needs, a recent study published in ACS Central Science discusses how organic cathode materials could be used as a substitute for cobalt for lithium-ion batteries while potentially offering similar levels of storage capacity and charging capabilities, as cobalt has shown to be financially, environmentally, and socially expensive.

“Cobalt batteries can store a lot of energy, and they have all of features that people care about in terms of performance, but they have the issue of not being widely available, and the cost fluctuates broadly with commodity prices,” said Dr. Mircea Dincă, who is a W.M. Keck Professor of Energy at MIT and a co-author on the study.

For their study, the researchers constructed a layered organic cathode comprised of cellulose, rubber, and other Earth-based elements. The team then subjected their organic cathode to a variety of tests, including energy storage, delivery, and charging capabilities. In the end, they found their cathode’s capabilities exceed most cobalt-based cathodes, including a charge-discharge time of 6 minutes. Additionally, while battery cathodes are known for significant wear and tear due to cracking from the flow of lithium ions, the researchers noted that the rubber and cellulose materials helped extend the battery cathode’s lifetime.