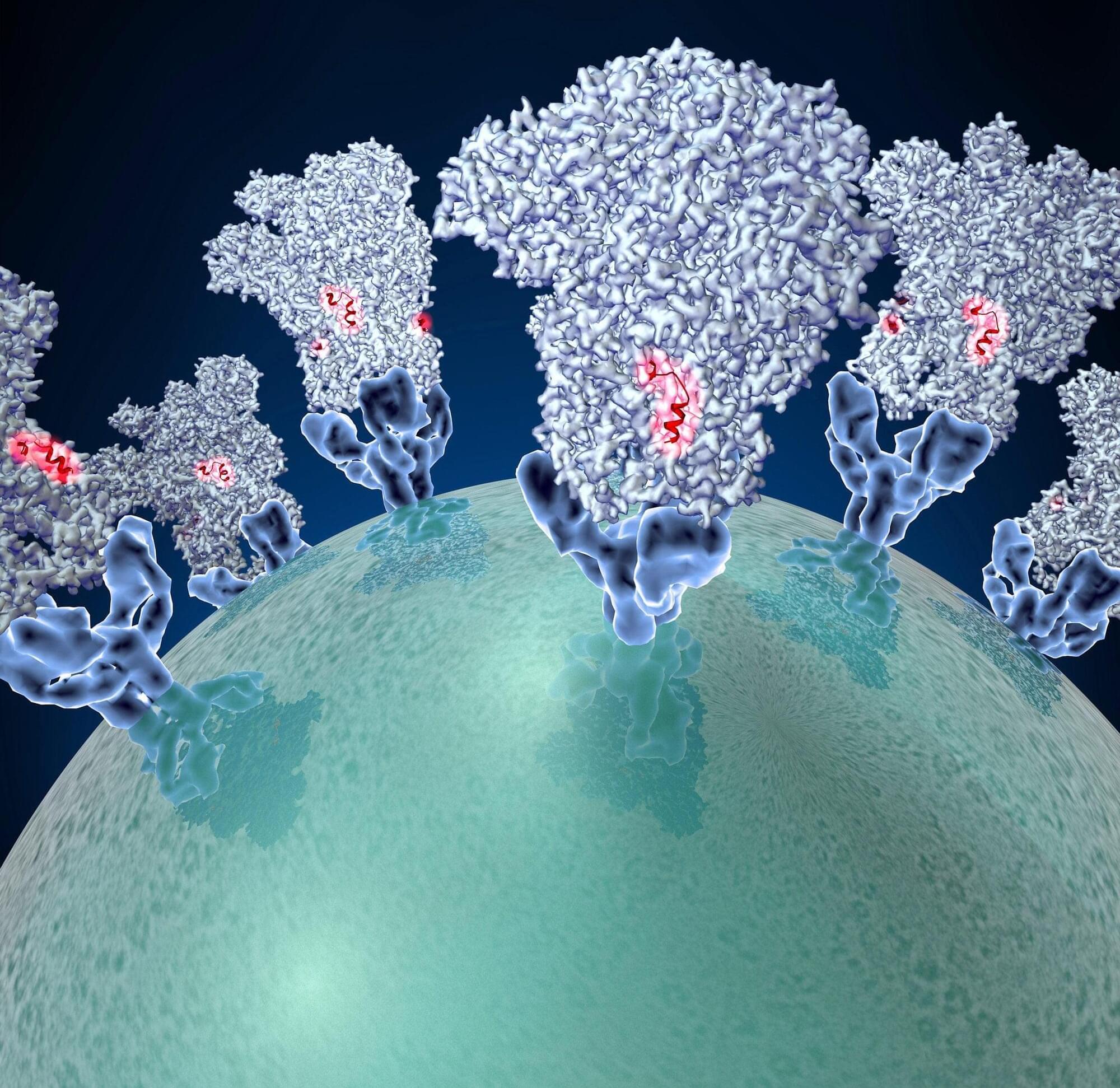

As population immunity continues to grow, understanding how immune responses influence both disease outcomes and viral evolution has become increasingly important.

Entropy is one of the most profound and misunderstood concepts in modern science — at once a physical quantity, a measure of uncertainty, and a metaphor for the passage of time itself. Entropy: The Order of Disorder explores this concept in its full philosophical and scientific depth, tracing its evolution from the thermodynamics of Clausius and Boltzmann to the cosmology of the expanding universe, the information theory of Shannon, and the paradoxes of quantum mechanics.

At the heart of this study lies a critical insight: entropy in its ideal form can exist only in a perfectly closed and isolated system — a condition that is impossible to realize, even for the universe itself. From this impossibility arises the central tension of modern thought: the laws that describe equilibrium govern a world that never rests.

Bridging physics, philosophy, and cosmology, this book examines entropy as a universal principle of transformation rather than decay. It situates the second law of thermodynamics within a broader intellectual landscape, connecting it to the philosophies of Heraclitus, Kant, Hegel, and Whitehead, and to contemporary discussions of information, complexity, and emergence.

The concept of cancer vaccines has developed over the last century with initial promise from a young doctor, William Coley. In the late 19th to early 20th century Dr. Coley developed a treatment that elicited strong immune response. This elixir was referred to as Coley’s toxin, which comprised of bacteria that generated an inflammatory response in patients. As a result, the generated response recognized and targeted the patient’s tumor. However, his treatment did not yield consistent clinical benefit. He also had his critics among physicians. At the time, the scientific community debated how safe the toxin was and whether it really worked. Colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering and other top institutions questioned Coley’s motive for the toxin, since there was little empirical data or scientific basis for its use. Although Coley’s toxin proved to be an inconsistent treatment, it laid the foundation for future immunotherapies as preventative and therapeutic cancer vaccines were developed.

Cancer vaccines were limited in their ability to effectively treat patients with cancer. Preventative cancer vaccines are difficult to developed because of the uncertainty to predict the onset of mutations in patients. Currently, the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved preventative cancer vaccine is for the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. While it directly protects against HPV, the vaccine indirectly prevents a multitude of cancers, including cervical, anal, and genital. Additionally, researchers have previously struggled to generate a therapeutic vaccine that elicits a strong immune response with limited adverse effects. However, a reinvigorated interest has emerged in therapeutic vaccines due to improved delivery platforms and better biomarkers to target on cancer.

Recently, an article in Cell Reports Medicine, by Dr. Nina Bhardwaj and others, examined the evolution of cancer vaccines. Specifically, the paper focused on tumor biomarker-based vaccines, which are highly personalized and designed to target genetic mutations specific to a patient’s tumor. Bhardwaj is a physician scientist, the Ward-Coleman Chair in Cancer Research, and Director of Vaccine and Cell Therapy Laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Her work focuses on improving vaccine strategies to provide strong single agent affect against tumors. Bhardwaj’s group studies different cellular pathways to understand how to therapeutically target cancer.

The trajectory of a storm, the evolution of stock prices, the spread of disease — mathematicians can describe any phenomenon that changes in time or space using what are known as partial differential equations. But there’s a problem: These “PDEs” are often so complicated that it’s impossible to solve them directly.

Mathematicians instead rely on a clever workaround. They might not know how to compute the exact solution to a given equation, but they can try to show that this solution must be “regular,” or well-behaved in a certain sense — that its values won’t suddenly jump in a physically impossible way, for instance. If a solution is regular, mathematicians can use a variety of tools to approximate it, gaining a better understanding of the phenomenon they want to study.

But many of the PDEs that describe realistic situations have remained out of reach. Mathematicians haven’t been able to show that their solutions are regular. In particular, some of these out-of-reach equations belong to a special class of PDEs that researchers spent a century developing a theory of — a theory that no one could get to work for this one subclass. They’d hit a wall.

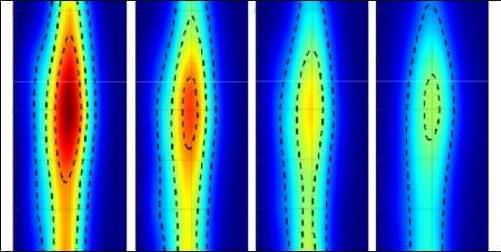

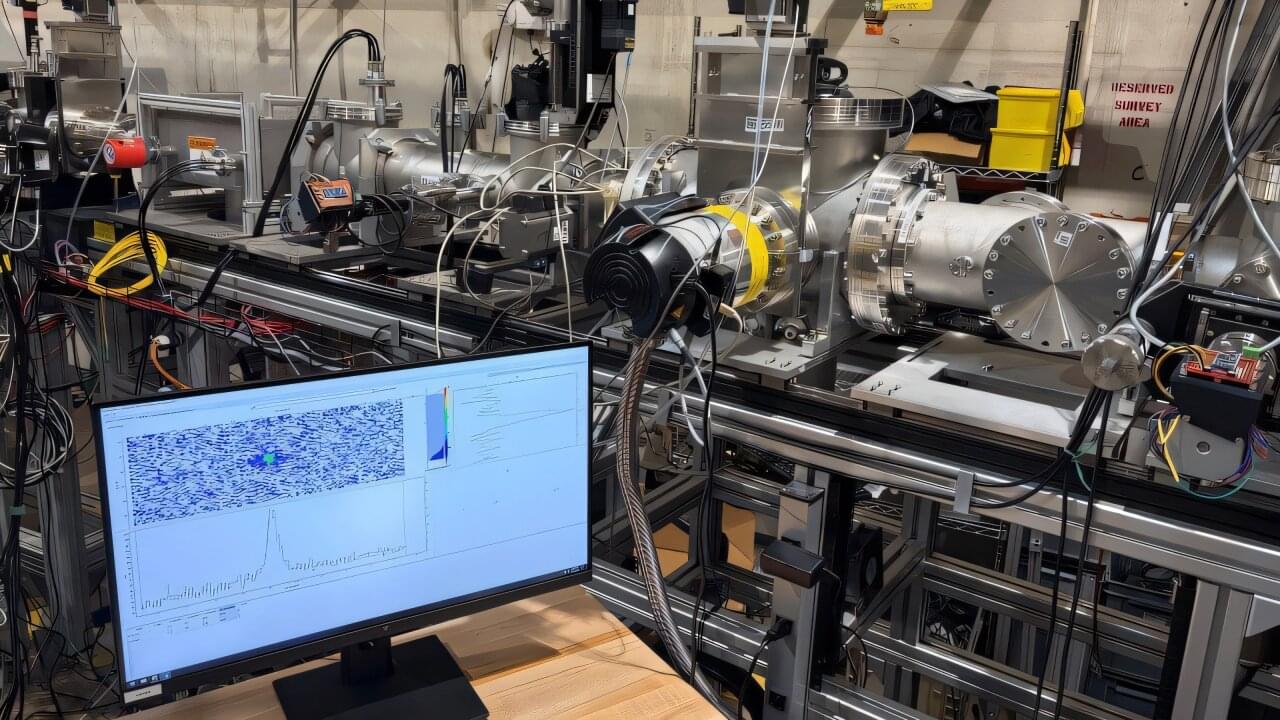

Using a camera with 2-picosecond time resolution, researchers show that the atoms in a laser-induced plasma are more highly ionized than theory predicts.

With an astonishing 500 billion frames per second, a new movie captures the evolution of a laser-induced plasma, revealing that its atoms have lost more electrons—and thus have stronger interactions within the plasma—than models predict [1]. The movie relies on a ten-year-old technology, called compressed ultrafast photography (CUP), that packs all the information for hundreds of movie frames into a single image. The results suggest that models of plasma formation may need revising, which could have implications for inertial-confinement-fusion experiments, such as those at the National Ignition Facility in California.

Dense plasmas occur in many astrophysical settings and laboratory experiments. Their behavior is difficult to predict, as they often change on picosecond (10−12 s) timescales. A traditional method for probing this behavior is to use a streak camera, which collects a movie on a single image by capturing a small slice of each movie frame. “It’s one picture, but every line occurs at a different time,” explains John Koulakis from UCLA. He and his colleagues have used streak cameras to study anomalous behavior in plasmas [2], but the small region of plasma visible with this technique left doubts about what they were seeing, he says.

A novel apparatus at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory has made extremely precise measurements of unstable ruthenium nuclei. The measurements are a significant milestone in nuclear physics because they closely match predictions made by sophisticated nuclear models.

“It’s very difficult for theoretical models to predict the properties of complex, unstable nuclei,” said Bernhard Maass, an assistant physicist at Argonne and the study’s lead author. “We have demonstrated that a class of advanced models can do this accurately. Our results help to validate the models.”

Validating the models can build trust in their predictions about astrophysical processes. These include the formation, evolution and explosions of stars where elements are created.

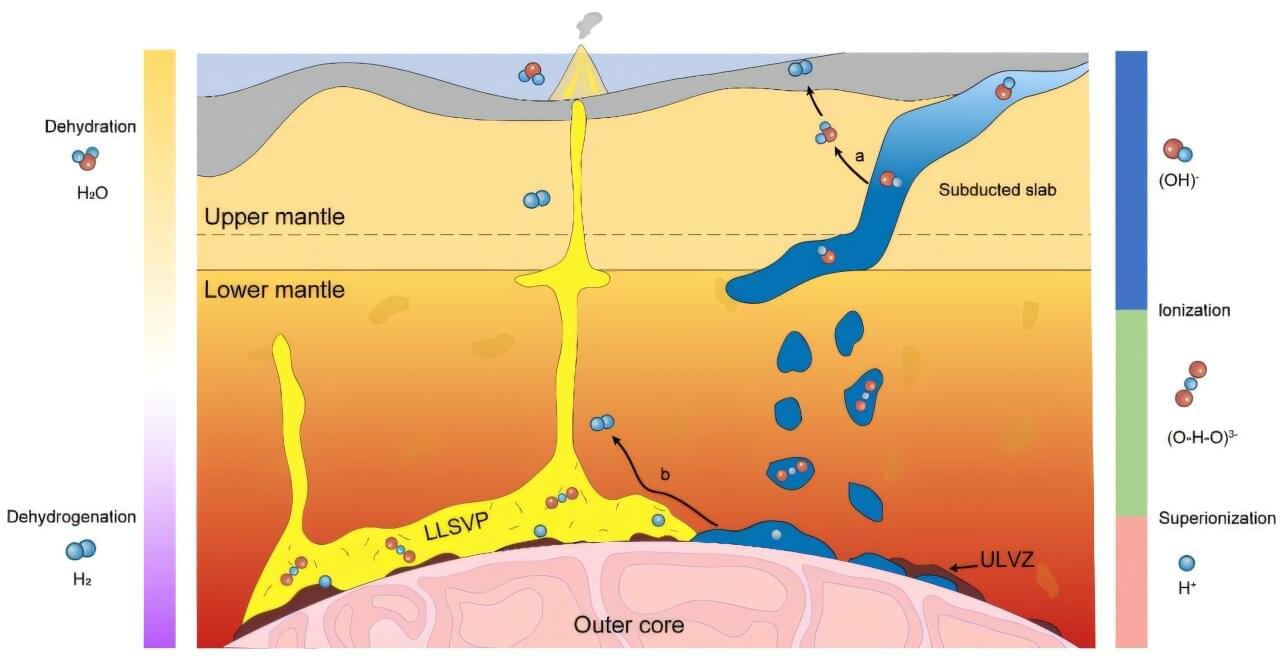

The cycling of water within Earth’s interior regulates plate tectonics, volcanism, ocean volume, and climate stability, making it central to the planet’s long-term evolution and habitability and a key scientific question. While subducting slabs are known to transport water into the mantle, scientists have long assumed that most hydrous minerals dehydrate at high temperatures, releasing fluids as they descend.

Whether water can survive the extreme conditions of the deep lower mantle, however, has remained an open question.

The platypus is one of evolution’s lovable, oddball animals. The creature seems to defy well-understood rules of biology by combining physical traits in a bizarre way. They’re egg-laying mammals with duck bills and beaver-like tails, and the males have venomous spurs on their hind feet. In that regard, it’s only fitting that astronomers describe some newly discovered oddball objects as “Astronomy’s Platypus.”

The discovery consists of nine galaxies that also have unusual properties and seem to defy categorization. The findings were recently presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix. The results are also in new research titled “A New Population of Point-like, Narrow-line Objects Revealed by the James Webb Space Telescope,” posted to the arXiv preprint server. The lead author is Haojing Yan from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

“We report a new population of objects discovered using the data from the James Webb Space Telescope, which are characterized by their point-like morphology and narrow permitted emission lines,” the authors write in their research. “Due to the limitation of the current data, the exact nature of this new population is still uncertain.”

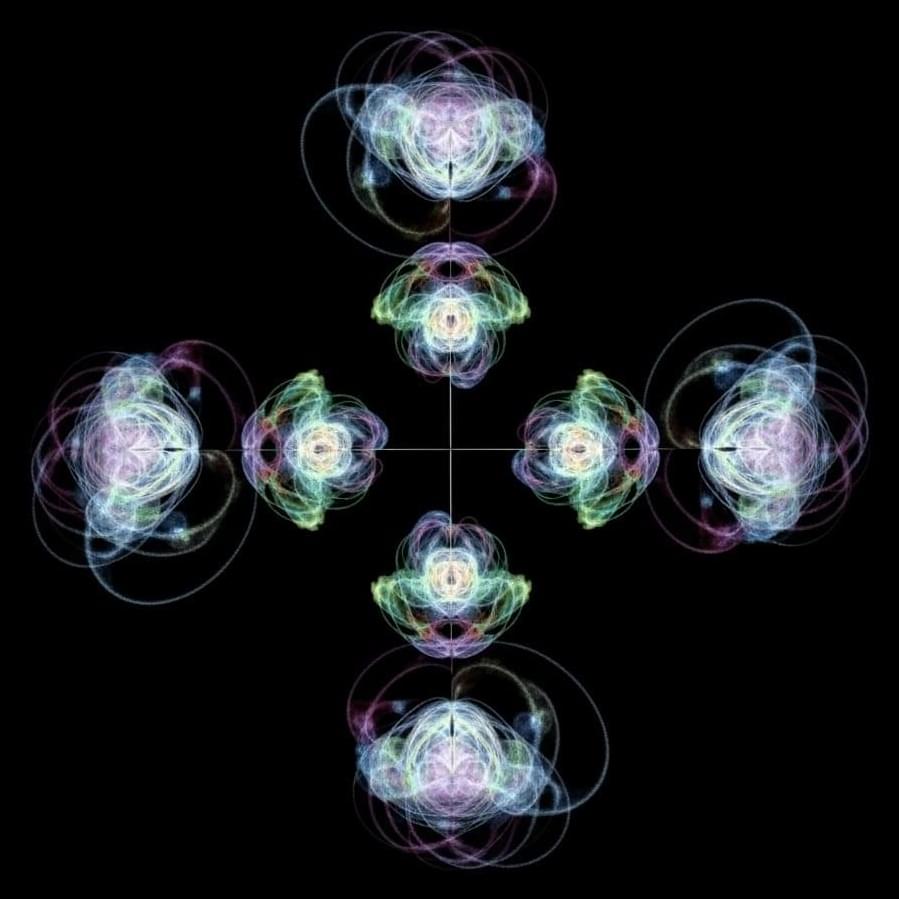

The research extends beyond theoretical analysis by outlining a feasible experimental implementation using integrated photonics. This includes a detailed description of the required optical components and control sequences for realising the ICO gate and performing the quantum sensing measurements. By leveraging the advantages of integrated photonics, the proposed scheme offers a pathway towards compact and scalable quantum sensors with enhanced performance characteristics. The findings pave the way for practical applications in fields such as precision metrology, biomedical imaging, and materials science.

Indefinite Causal Order for Real-Time Error Correction

Realistic noisy devices present significant challenges to quantum technologies. Quantum error correction (QEC) offers a potential solution, but its implementation in quantum sensing is limited by the need for prior noise characterisation, restrictive signal, noise compatibility conditions, and measurement-based syndrome extraction requiring global control. Researchers have now introduced an ICO-based QEC protocol, representing the first application of indefinite causal order (ICO) to QEC. By coherently integrating auxiliary controls and noisy evolution within an indefinite causal order, the resulting noncommutative interference allows an auxiliary system to herald and correct errors in real time.

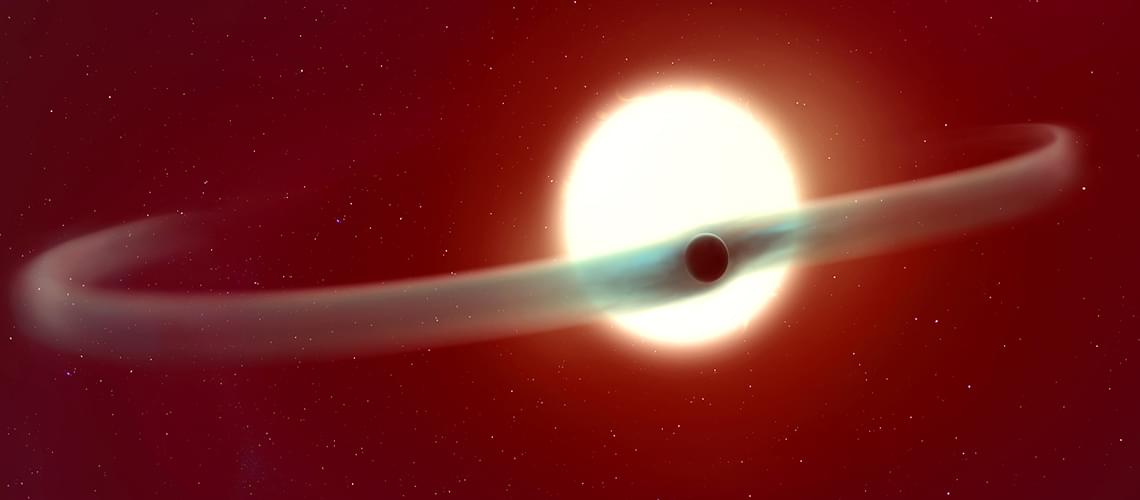

“We were incredibly surprised to see how long the helium escape lasted,” said Dr. Romain Allart.

What effects can an exoplanet orbiting close to its star have on the former’s atmosphere? This is what a recent study published in Nature Communications hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated a unique atmospheric phenomenon of an ultra-hot Jupiter, the latter of which are exoplanets that orbit extremely close to their stars, and the intense heat causes their atmospheres to slowly strip away. This study has the potential to help scientists better understand the formation and evolution of ultra-hot Jupiters and their solar systems, and where we could search for life beyond Earth.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data obtained by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) for the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-121b, which is located approximately 880 light-years from Earth and orbits its F-type star in only 1.3 days. For context, F-type stars are larger and hotter than our Sun—which is a G-type star—and the closest planet to our Sun—Mercury—orbits our Sun in 88 days. What makes WASP-121b intriguing is not only is its helium atmosphere is slowly being stripped away, also called atmospheric escape, but the data revealed that this has resulted in two helium tails wrapping around WASP-121b while circling approximately 60 percent of the exoplanet’s orbit.