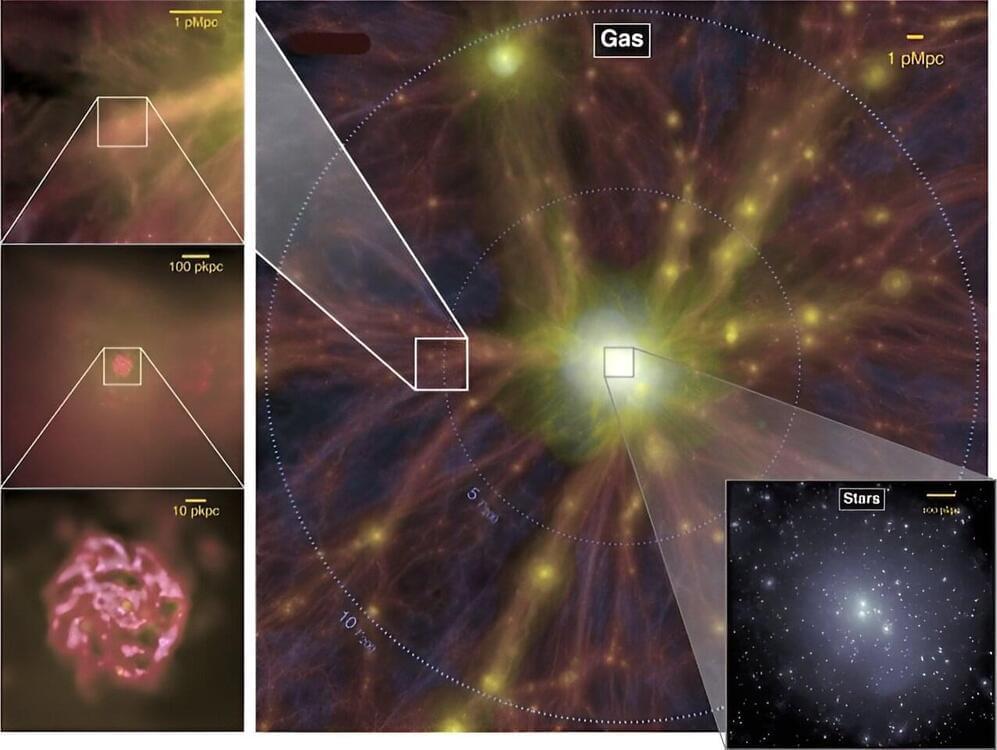

SANTIAGO, Chile — Astronomers have traced the source of Earth’s oceans, rivers, and lakes back to a stellar nursery located 1,300 light years away. They’re describing this finding as the “missing link” in the evolution of life as we know it.

“We can now trace the origins of water in our Solar System to before the formation of the Sun,” says lead author Dr. John Tobin of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

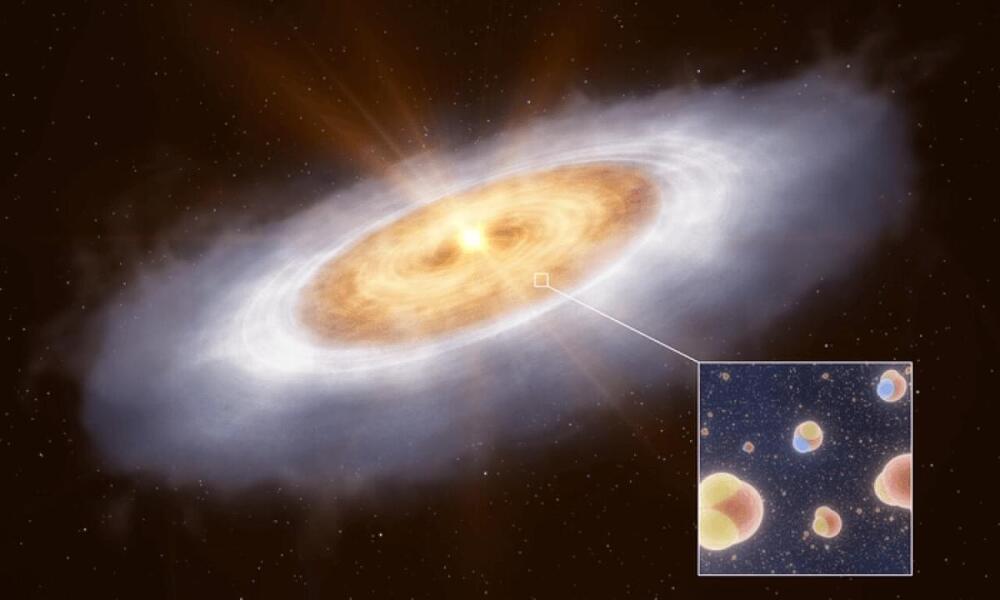

The international team discovered gaseous water in a substantial planet-forming disc around the star V883 Orionis. This star, located in the Orion constellation in the southwestern sky, was studied using the ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) telescope in Chile. Upon examination, researchers found that the disc contained at least 1,200 times the quantity of water found in all of Earth’s oceans. This discovery could potentially aid researchers in identifying planets or moons that are most likely to harbor extraterrestrial life.