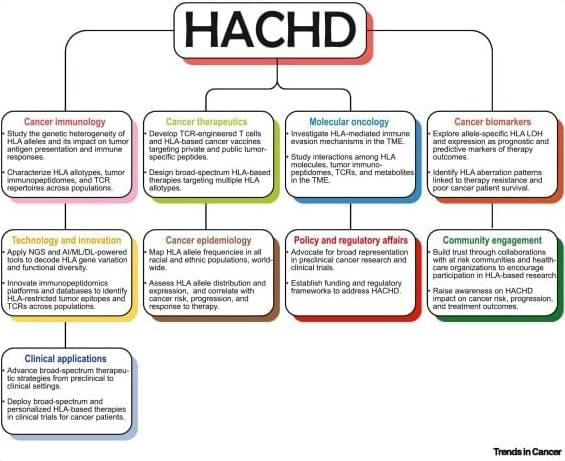

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-based immunotherapeutics, such as tebentafusp-tebn and afamitresgene autoleucel, have expanded the treatment options for HLA-A*02-positive patients with rare solid tumors such as uveal melanoma, synovial sarcoma, and myxoid liposarcoma. Unfortunately, many patients of European, Latino/Hispanic, African, Asian, and Native American ancestry who carry non-HLA-A*02 alleles remain largely ineligible for most current HLA-based immunotherapies. This comprehensive review introduces HLA allotype-driven cancer health disparities (HACHD) as an emerging research focus, and examines how past and current HLA-targeted immunotherapeutic strategies may have inadvertently contributed to cancer health disparities. We discuss several preclinical and clinical strategies, including the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI), to address HACHD.