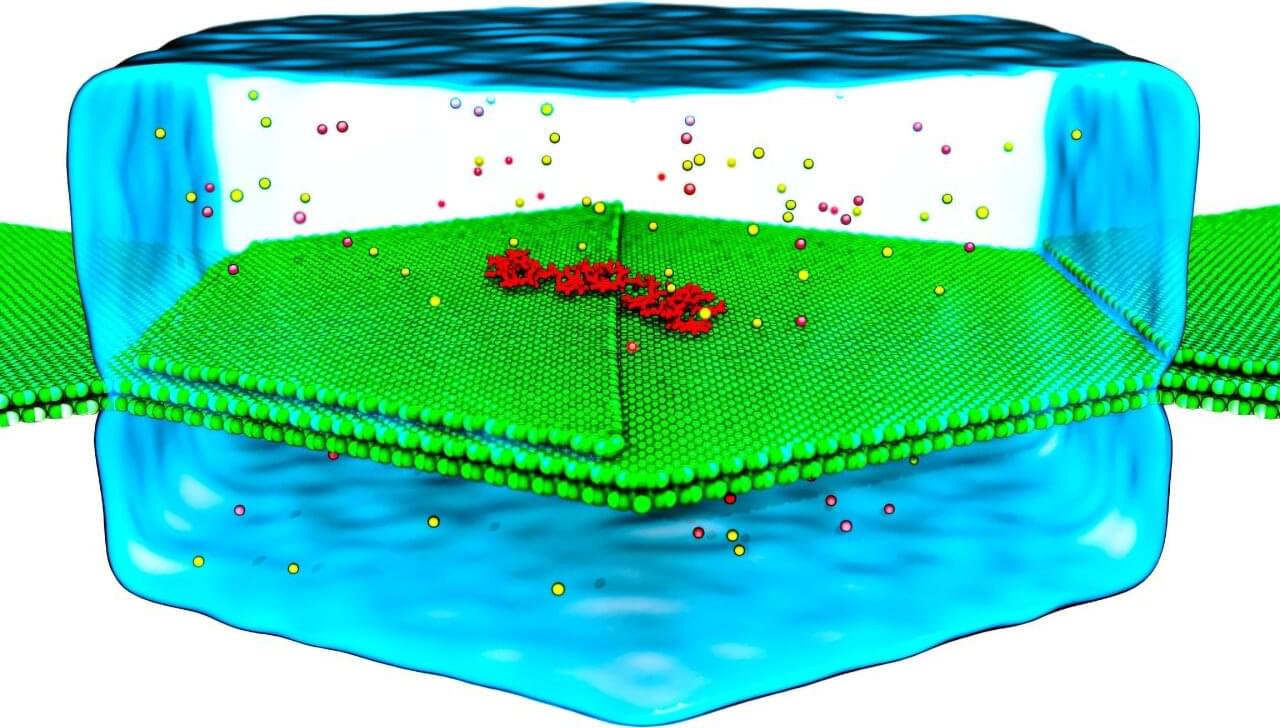

Pictures of DNA often look very tidy—the strands of the double helix neatly wind around each other, making it seem like studying genetics should be relatively straightforward. In truth, these strands aren’t often so perfectly picturesque. They are constantly twisting, bending, and even being repaired by minuscule proteins. These are movements on the nanoscale, and capturing them for study is extremely challenging. Not only do they wriggle about, but the camera’s fidelity must be high enough to focus on the tiniest details.

Researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U. of I.) have been working on resolving a grand challenge for molecular biology, and more specifically, genetic research: how to take a high-resolution image of DNA to facilitate study.

Using a number of compute resources, including NCSA’s Delta, Aleksei Aksimentiev, a professor of physics at U. of I, and Dr. Kush Coshic, formerly a graduate research assistant in the Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at U. of I., and currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, recently made significant contributions to solving this challenge. They did it by focusing on two specific problems: creating a “camera” that could capture the molecular movement of DNA, and by creating an environment in which they could predictably direct the movement of the DNA strands.