A team of researchers at NYU Abu Dhabi has uncovered a key mechanism that helps shape how our brains are wired, and what can happen when that process is disrupted.

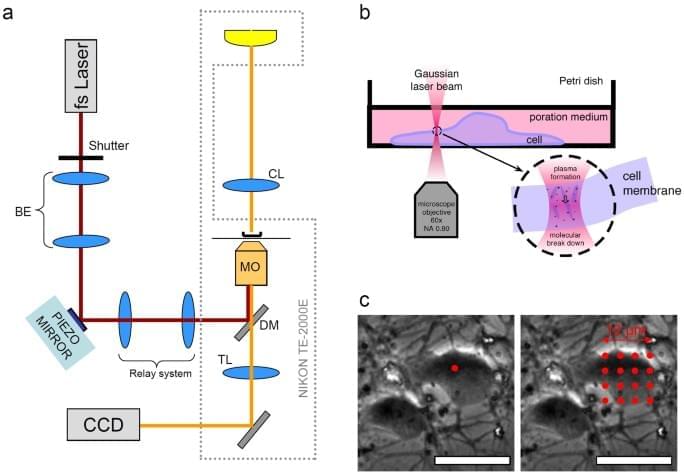

In a new study published in Cell Reports, the RNA-MIND Lab at NYU Abu Dhabi, led by Professor of Biology Dan Ohtan Wang, with Research Associate Belal Shohayeb, reveals how a small molecular mark on messenger RNA, called m6A methylation, regulates the production of essential proteins inside growing neurons. This process plays a critical role in the development of axons, the long extensions that neurons use to connect and communicate with each other.

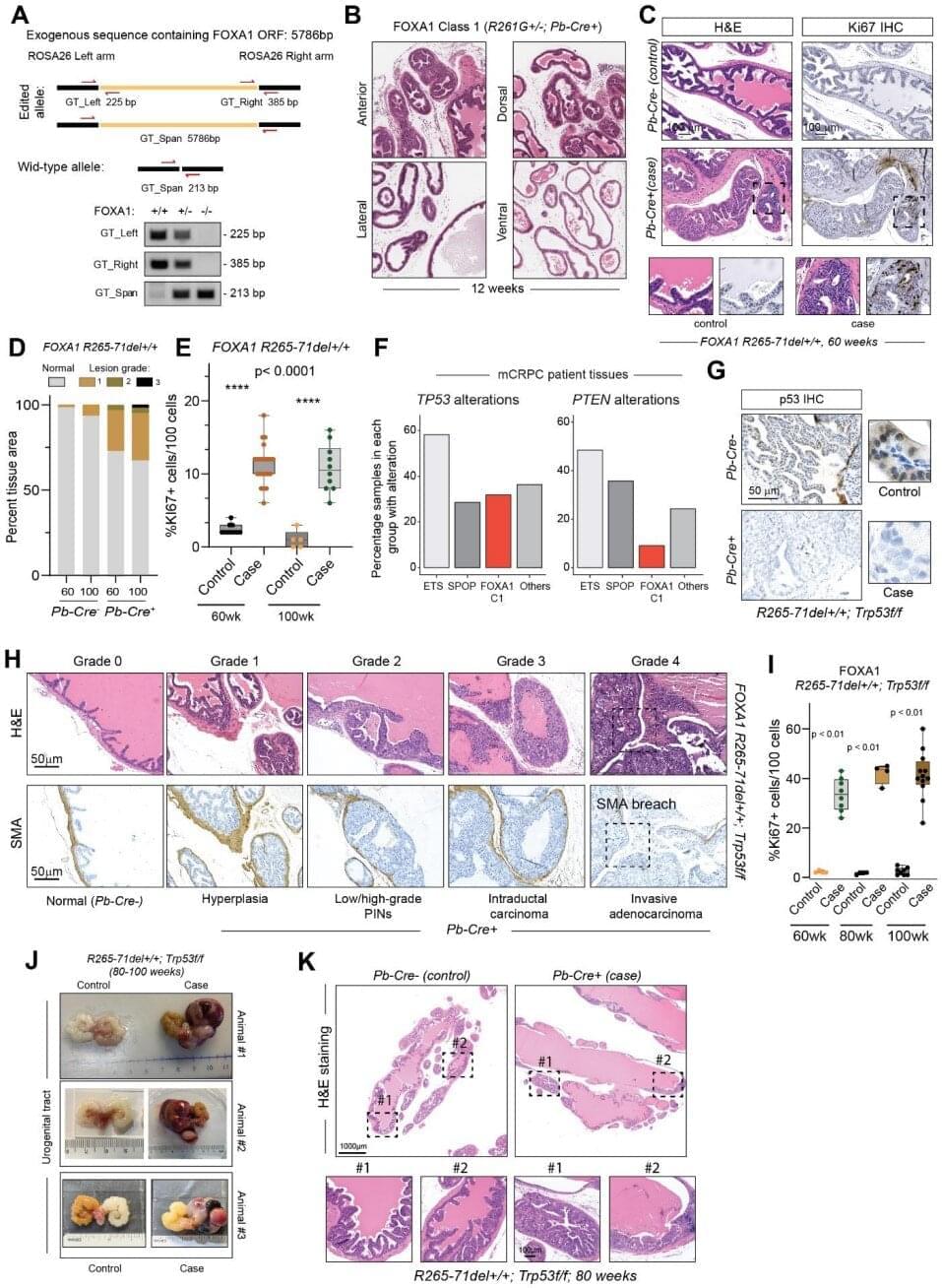

The study shows that this molecular mark controls the production of a protein called adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), which helps organize the internal structure of nerve cells and is needed to locally produce β-actin, a key building block of the cytoskeleton to support axon growth. Importantly, the team also found that genetic mutations linked to autism and schizophrenia can interfere with this process, potentially affecting how the brain develops.