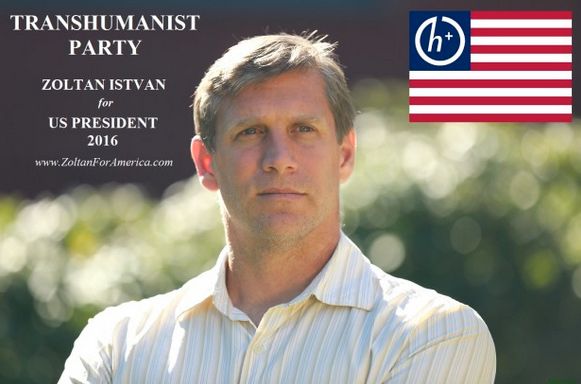

A new article from The Daily Dot on transhumanism and my campaign:

The Daily Dot is the hometown newspaper of the World Wide Web, reporting on Reddit, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and more.

A new article from The Daily Dot on transhumanism and my campaign:

The Daily Dot is the hometown newspaper of the World Wide Web, reporting on Reddit, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and more.

A video on transhumanism, the Transhumanist Party, and my presidential campaign is out on BuzzFeed. It starts right before the 8-min mark and goes for 5 minutes. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOPSDcN0t8w and BuzzFeed site: http://www.buzzfeed.com/brandensueper/does-technology-contro.…jfGPZ2bka

We’re all going to die. Check out more awesome videos at BuzzFeedVideo! http://bit.ly/YTbuzzfeedvideo MUSIC Lizard Lounge Mrs Rossas Smile Pluck And Blow Und…

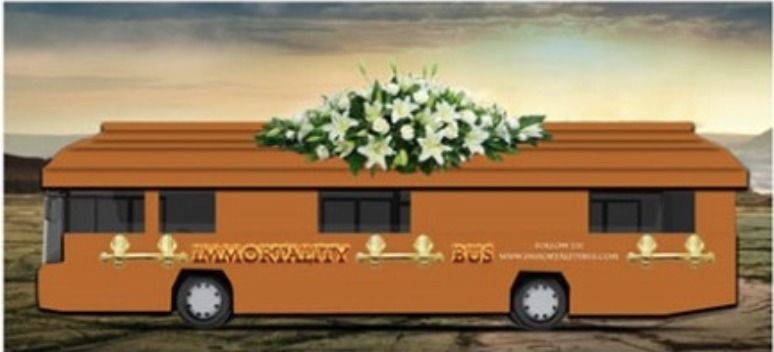

My new story for Vice Motherboard exploring the human journey into eventually becoming a machine: http://motherboard.vice.com/read/why-i-advocate-for-becoming-a-machine And also if you haven’t donated to the Immortality Bus Indiegogo campaign, there are only a few hours left to do so: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/immortality-bus-with-pres…406#/story

Biology is simply not the best system out there for our species’ evolution. It’s frail, terminal, and needs to be upgraded. In fact, even machines may be upgraded in the future too, and rendered as junk as our intelligences figure out ways to become beings of pure organized energy. “Onward” is the classic transhumanist mantra.

No matter what happens, to move forward in the transhumanist age, we need to let go of our egos and our shallow sense of identity; in short, we need to get over ourselves. The permanence of our species lies in our ability to reason, think, and remember who we are and where we’ve been. The rest is just an impermanent shell that changes—and it has already been changing for tens of millions of years in the form of sentient evolution.

Zoltan Istvan is a futurist, author of The Transhumanist Wager, and founder of and presidential candidate for the Transhumanist Party. He writes an occasional column for Motherboard in which he ruminates on the future beyond natural human ability.

https://youtube.com/watch?a&feature=youtu.be&v=TFErQ3XM__c

An interview on transhumanism done by London Real:

Zoltan Istvan — Transhumanist — PART 1/2. FREE FULL EPISODE: http://londonreal.tv/zoltan-istvan This week’s guest on London Real is Zoltan Istvan, US Presidential candidate for the Transhumanist Party. Istvan’s stated aim is to “change the conversation” on transhumanism.

Transhumanism could be described as the use of technology to enhance human capabilities, both mental and physical.

As Istvan points out in this interview, the ultimate goal is transcending biological death.

This is an interesting story in one of Italy’s top 3 papers/sites about life extension science and millennials living beyond 100 years of age. It also features transhumanism: http://numerus.corriere.it/2015/08/06/i-millennials-camperan…ermettere/ and the English: https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=it&u=http://…rev=search

Le tendenze della statistica ci dicono che chi oggi ha vent’anni ha ottime probabilità di arrivare ai cento in buona salute. Forse anche molto di più, se avranno successo le battaglie del Partito Transumanista che si presenta alle elezioni americane del 2016 con l’obiettivo di puntare più risorse sulla lotta all’invecchiamento. Ma come si configura un mondo di persone tanto longeve? L’allungamento della vita potrà beneficiare tutte le popolazioni o soltanto una fascia di privilegiati? Già oggi la speranza di vita nei Paesi più poveri è mediamente inferiore di 18 anni rispetto ai Paesi più ricchi e anche in Italia ci sono tre anni di differenza tra Milano e Napoli. E come si ridisegna un sistema sociale nel quale le persone vivranno venti o trent’anni più di oggi?

Un autobus rosso a forma di bara, con tanto di fiori finti sul tetto, percorre le strade degli Stati Uniti. Lo ha voluto il leader del Partito transumanista Zoltan Istvan, candidato alle elezioni presidenziali del 2016. Istvan non diventerà presidente, ma il suo messaggio non è banale: con il suo tour elettorale, vuole attirare l’attenzione sulla battaglia contro l’invecchiamento. Chiede più fondi per la ricerca e per le cure sanitarie, più carriere nelle attività tecnologiche, nell’intelligenza artificiale e nella medicina.

.

.

An interview on transhumanism, Transhumanist Party, and longevity science in Quartz, which is the business site of Atlantic Media:.

One of the biggest existential challenges that transhumanists face is that most people don’t believe a word we’re saying, however entertaining they may find us. They think we’re fantasists when in fact we’re talking about a future just over the horizon. Suppose they’re wrong and we are right. What follows? Admittedly, we won’t know this until we inhabit that space ‘just over the horizon’. Nevertheless, it’s not too early to discuss how these naysayers will be regarded, perhaps as a guide to how they should be dealt with now.

So let’s be clear about who these naysayers are. They hold the following views:

1) They believe that they will live no more than 100 years and quite possibly much less.

2) They believe that this limited longevity is not only natural but also desirable, both for themselves and everyone else.

3) They believe that the bigger the change, the more likely the resulting harms will outweigh the benefits.

Now suppose they’re wrong on all three counts. How are we to think about such beings who think this way? Aren’t they the living dead? Indeed. These are people who live in the space of their largely self-imposed limitations, which function as a self-fulfilling prophecy. They are programmed for destruction – not genetically but intellectually. Someone of a more dramatic turn of mind would say that they are suicide bombers trying to manufacture a climate of terror in humanity’s existential horizons. They roam the Earth as death-waiting-to-happen. This much is clear: If you’re a transhumanist, ordinary people are zombies.

Zombies are normally seen as either externally revived corpses or bodies in a state between life and death – what Catholics call ‘purgatory’. In both cases, they remain on Earth beyond their will. So how does one deal with zombies, especially when they are the majority of the population? There are three general options:

1) You kill them, once and for all.

2) You avoid them.

3) You enable them to be fully alive.

The decision here is not as straightforward as it might seem because the prima facie easiest option (2) requires that there are no resource implications. But of course, zombies require living humans (i.e. potential transhumans) in order to exist in the manner they do, which in turn makes the zombies dangerous; hence (1) has always proved such an attractive option for dealing with zombies. After all, it is difficult to dedicate the resources needed to secure the transhumanist goal of indefinite longevity, if there are zombies trying to anchor your existential horizons in the present to make their own lives as easy as possible.

This kind of problem normally arises in the context of ecological sustainability as ‘care for future generations’: Our greedy habits of mass consumption blind us to the long-term damage it does to the environment. However, the relevant sense of ‘care’ in the transhumanist case relates to sustaining the investment base needed to reach a state of indefinite longevity. It may require diverting public resources from seemingly more pressing needs, such as having a strong national defence — as the US Transhumanist Party presidential candidate Zoltan Istvan thinks. It is certainly true that if people routinely lived indefinitely, then the existential character of ‘the horror of war’ would be considerably reduced, which may in turn decrease both the likelihood and cost of war. Well, maybe…

So what about option (3), which is probably the one that most of us would find most palatable, at least in principle?

Here there is a serious public relations problem, one not so different from development aid workers trying to persuade ‘underdeveloped’ peoples that their lives would be appreciably improved by allowing their societies to be radically re-structured so as to double their life expectancy from 40 to 80. While such societies are by no means perfect and may require significant change to deliver what they promise their members, nevertheless the doubling of life expectancy would mean a radical shift in the rhythm of their individual and collective life cycles – which could prove quite threatening to their sense of identity.

Of course, the existential costs suggested here may be overstated, especially in a world where even poor people have decent access to more global trends. Nevertheless the chequered history of development aid since the formal end of Imperialism suggests that there is little political will – at least on the part of Western nations — to invest the human and financial capital needed to persuade people in developing countries that greater longevity is in their own long-term interest, and not simply a pretext to have them work longer for someone else.

The lesson for us lies in the question: How can we persuade people that extending their lives is qualitatively different from simply extending their zombiehood?

A nice article from Kurzweil AI on a transhumanist & life extension bus tour. If you haven’t contributed, please do so! Anyone from any country can donate, and even $5 helps! http://www.kurzweilai.net/transhumanist-party-presidential–… and the Indiegogo campaign: https://www.indiegogo.com/…/immortality-bus-with…/x/6837406…

July 9 update:

3 days after posting, Visa acknowledged that Bitcoin has a future in payments. This is an understatement, of course. The bank described below goes a step further by acknowledging that the entire financial infrastructure may cave to cryptocurrencies.

French bank BNP Paribas warned customers and investors that the technology behind bitcoin might one day overtake conventional, account-based financial institutions, thus rendering existing companies redundant (that’s British for “obsolete”).* It’s a tectonic acknowledgement from one of the world’s biggest banks.

Analyst Johann Palychata writes in the company’s magazine Quintessence that Bitcoin’s blockchain, the underlying architecture that allows cryptocurrency to function, “should be considered as an invention like the steam or combustion engine,” that has the potential to transform the world of finance and beyond.

Check out the full story by Oscar Williams-Grut at Business Insider.

* Although Bitcoin will obsolete the current service mix of financial institutions, it is my opinion that for savvy governments and established businesses, it represents a long term opportunity rather than a threat. —PR

__________

Philip Raymond is Co-Chair of The Cryptocurrency Standards

Association [crypsa.org] and chief editor at AWildDuck.com

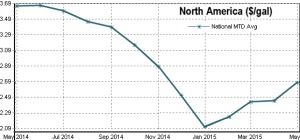

It’s been awhile since the cost of gasoline topped $4 in the U.S. The national average hit $4.11 on July 11, 2008 and came close in May 2011 at $3.96. On New Years Day 2015, I drove through the night from Chicago to Boston. Despite the cold weather, the economics of fuel made it the best day for a road trip in years. I bought gas at a Pilot service station just off the Ohio Turnpike at $1.92/gallon. For me, it seemed like a bargain. Yet, 23 states charge less for gasoline than Ohio.

Now, at the end of May 2015, gas is rebounding from that low. Drivers on Memorial Day weekend faced the highest cost for gasoline of the year so far.

It’s tempting for politicians to advocate using tax breaks to smooth price spikes. With energy often surpassing the expense of food and rent and with so many individuals using fuel to make a living, reducing user fees or taxes during periods of very high fuel cost seems like the humane thing to do.

It seems humane, but it has the opposite effect. In fact, it is deeply punitive! That’s because the cost of gas is not an act of nature, nor even of free market economics. It is a product of cartels, special interests, conflict and FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt). Offering relief during price spikes sustains demand while doing absolutely nothing to increase supply. This, in turn, exacerbates the spike, creates shortages for critical services and transfers enormous sums of money from consumers to producers. In effect, it is a free gift for producer nations.

In fact, consumers and consuming nations are best served by a raising taxes in lockstep with fuel price increases.

In May 2011, as gas prices were spiking to an all time high, a group calling itself National Taxpayers Union or NTU launched a $1.25 million campaign to fight energy taxes, like the fuel tax added to the cost of gasoline at the pump in most countries.* One of the group’s less controversial public service announcements (or more accurately, a lobbying effort) consist of magazine ads and videos that encourage Americans to write their legislators and demand a roll back of gas taxes whenever market prices spike.

I hate consumption taxes, especially the ones that target individual commodities or categories, such as alcohol, cigarettes, luxury purchases, or any system of import tariffs. They are a form of social engineering and they bastardize free markets. But when an energy consumer nation gives consumers breaks during periods of price spikes, the result counters the social intent. In fact, each time that oil prices rise, the best thing our government can do is to force them higher still! This may sound crazy, but when the supply of a commodity is controlled a few foreign cartels, it is no longer a commodity. Artificially lowering the consumer price by subsidizing the price simply stimulates consumption. It does not expand supply, and so the subsidy goes directly into suppliers’ pockets.

Apparently, I am not the only one who thinks that lower gas prices is a bad idea. Folling the 2011 gas spike (the highest cost gas spike in U.S. history), Motley Fool columnist, Travis Hoium filed an Op-Ed entitled, 3 Reasons the US Should Want Higher Oil Prices. (At the same time, I cautioned against tax relief tied to gasoline price hikes). His analysis and opinion is articulate and adequately supported, but none of his reasons point to the fundamental economic reason that for a country that aspires to energy independence, oil should be taxed higher whenever the market cost of externally sourced oil rises. Let me spell it out…

What happens if we lower the cost of a commodity to consumers in an effort to counteract a higher supply price? It doesn’t take an Economist to analyze. Since the supply is not increased, throwing a subsidy to the buyers “fuels” an even faster rise in prices and hands all that money to the supplier.

Let’s say that C = Amount of fuel needed for critical purposes

…getting to work, heating our home, manufacturing

Let’s say that D = Amount of fuel needed for discretionary purposes

…vacation travel, backyard BBQ, mowing the lawn, etc

Of course, with a limited personal budget, high fuel prices influence a consumer’s decision to classify an activity as ‘critical’ or ‘discretionary’. Additionally, the use of fuel is greatly affected by how efficiently you perform a task (taking a train to work instead of driving, vacationing nearby instead of far away, etc).

Foreign cartels wish to maintain high prices and high revenue, so they limit the foreign supply of oil. For them, it makes more sense to charge a lot of money for less product than to charge less money for a lot of product. If we consider again our classification of consumption into two categories, Critical and Discretionary, the supplier limits leave us with only enough fuel to support this much activity:

100%C + 80%(D)

Now if we counteract their production limits and insulate consumers from the higher cost, the formula doesn’t change. We continue to use just as much fuel.

In a free market, limited supply causes prices to rise and this forces consumers to cut back on discretionary use. Some consumers with less money must cut back on critical needs. That’s because some people can afford the keep buying and of course the cost of fuel rises.

In a free market — at least on our side of the ocean, this normally leads to several things — all of them very good:

• Increase exploration and domestic production (Motley Fool covers this one)

• Develop alternative fuels, especially domestic and environmentally friendly

• Increase conservation:

• Change modalities:

If consumers are suddenly subsidized when the cost of fuel rises, something terrible happens. Instead of producing more domestic energy, we are not at all affecting the supply. We are simply handing the foreign seller more cash — directly from the taxpayer to their pockets. And they didn’t even ask for it! They raise the cost by $1 per gallon and we give them $2 extra. Heck, why not? It makes us feel good.

What happens if we increase taxes when suppliers raise prices? First, we benefit by all the good things listed above.

Second, since some foreign suppliers are not truly constrained in their production (that is, they have plenty of oil), they will keep costs low in order to sustain revenue. There are plenty of places this “cost reduction” tax can be inserted: at point-of-sale, at import, or in the distribution chain.

What do we do with the money that is raised by taxes? That’s easy too. Give it back to consumers or use it to fund the development of energy sources that are domestic, inexpensive and environmentally safe.

This is how supply and demand should work. Of course, the government can still subsidize those in need. But do it in a way that doesn’t bastardize market dynamics. As a society, we provide assistance to the consumers who cannot afford energy for critical needs, and not by handing money to the supplier (effectively, a reward for cutting production). In this way, we reduce consumption, increase domestic production and provide direct assistance to those who are less fortunate. The effect of subsidizing some buyers will force some other buyers to reduce discretionary use. For example, if some of the higher cost went to taxes, it could be used to help ease the consumers who can no longer afford the “critical” fraction of their use.

_____________

* Americans are taxed for automotive fuel at the pump: A federal tax of 18.4¢ plus a state tax that varies between 12~35¢. The average state tax is about 23¢/gal, so the typical American pays about 41½¢ tax on each gallon, or approximately 10%.

Philip Raymond is Co-Chair of The Cryptocurrency Standards Association and CEO of Vanquish Labs.

An earlier draft of this article was published in his Blog.