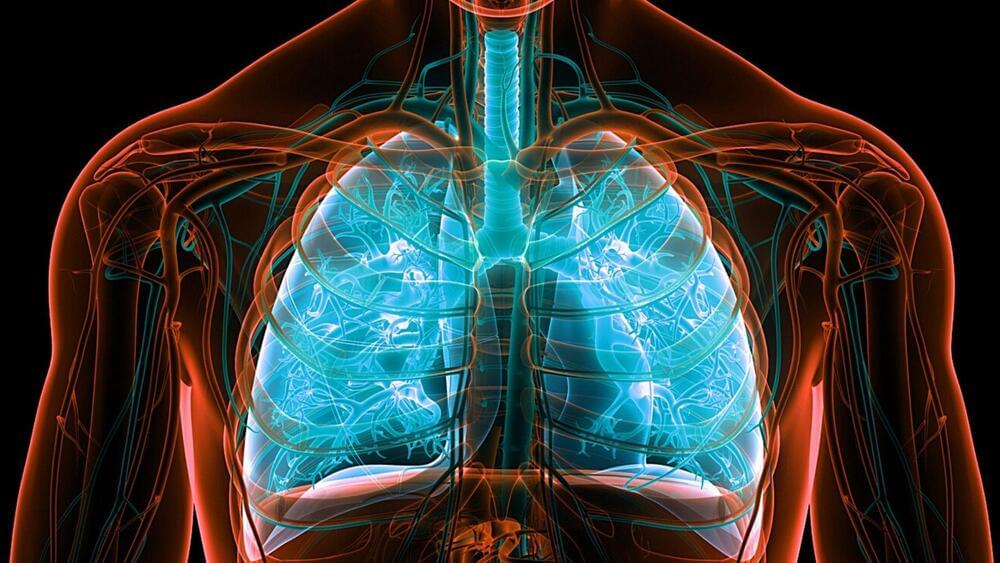

An algorithm developed by researchers from Helmholtz Munich, the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and its University Hospital rechts der Isar, the University Hospital Bonn (UKB) and the University of Bonn is able to learn independently across different medical institutions. The key feature is that it is self-learning, meaning it does not require extensive, time-consuming findings or markings by radiologists in the MRI images.

This federated algorithm was trained on more than 1,500 MRI scans of healthy study participants from four institutions while maintaining data privacy. The algorithm then was used to analyze more than 500 patient MRI scans to detect diseases such as multiple sclerosis, vascular disease, and various forms of brain tumors that the algorithm had never seen before. This opens up new possibilities for developing efficient AI-based federated algorithms that learn autonomously while protecting privacy. The study has now been published in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence.

Health care is currently being revolutionized by artificial intelligence. With precise AI solutions, doctors can be supported in diagnosis. However, such algorithms require a considerable amount of data and the associated radiological specialist findings for training. The creation of such a large, central database, however, places special demands on data protection. Additionally, the creation of the findings and annotations, for example the marking of tumors in an MRI image, is very time-consuming.