Parachutes have many applications, decelerating everything from skydivers to supersonic-speed scientific payloads. Regardless of what a parachute is slowing down, two things remain constant: the parachute must withstand large amounts of force, and it is crucial to ensuring the safety of whatever it’s carrying. To choose parachute materials that do their jobs effectively, it’s important to fully understand what happens while a parachute is opening and on its way down.

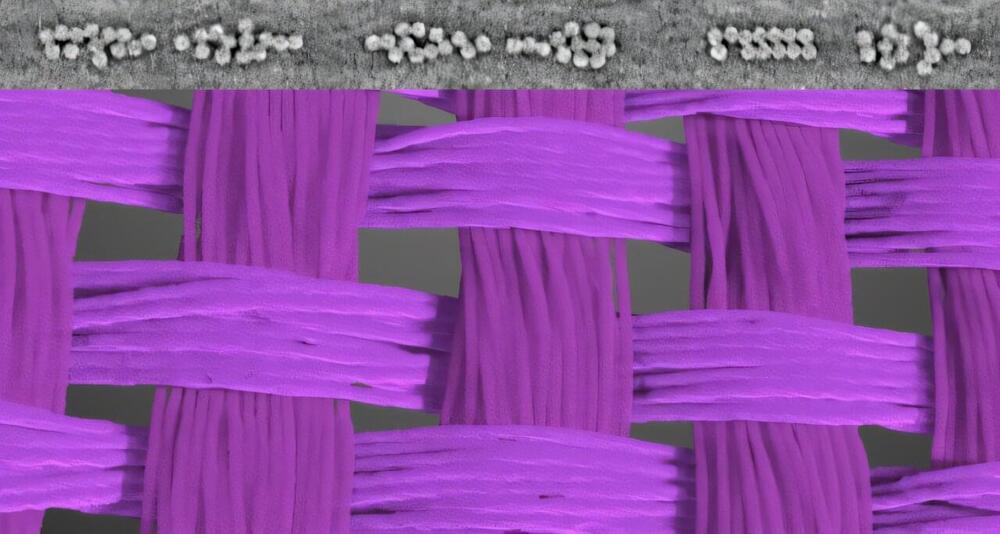

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology researchers Cutler Phillippe, Francesco Panerai and Laura Villafañe Roca have used computed tomography scans to study the fiber-scale properties of parachute textiles and link them to larger-scale behavior. Their work is published in the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Journal.

“We know generally how a textile impacts the performance of the parachute,” said Phillippe, a graduate student in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “But we don’t know from an experimental standpoint how that performance is related to the individual fiber motions within the textile as well as the dynamic properties of, for example, a bundle of fibers.”