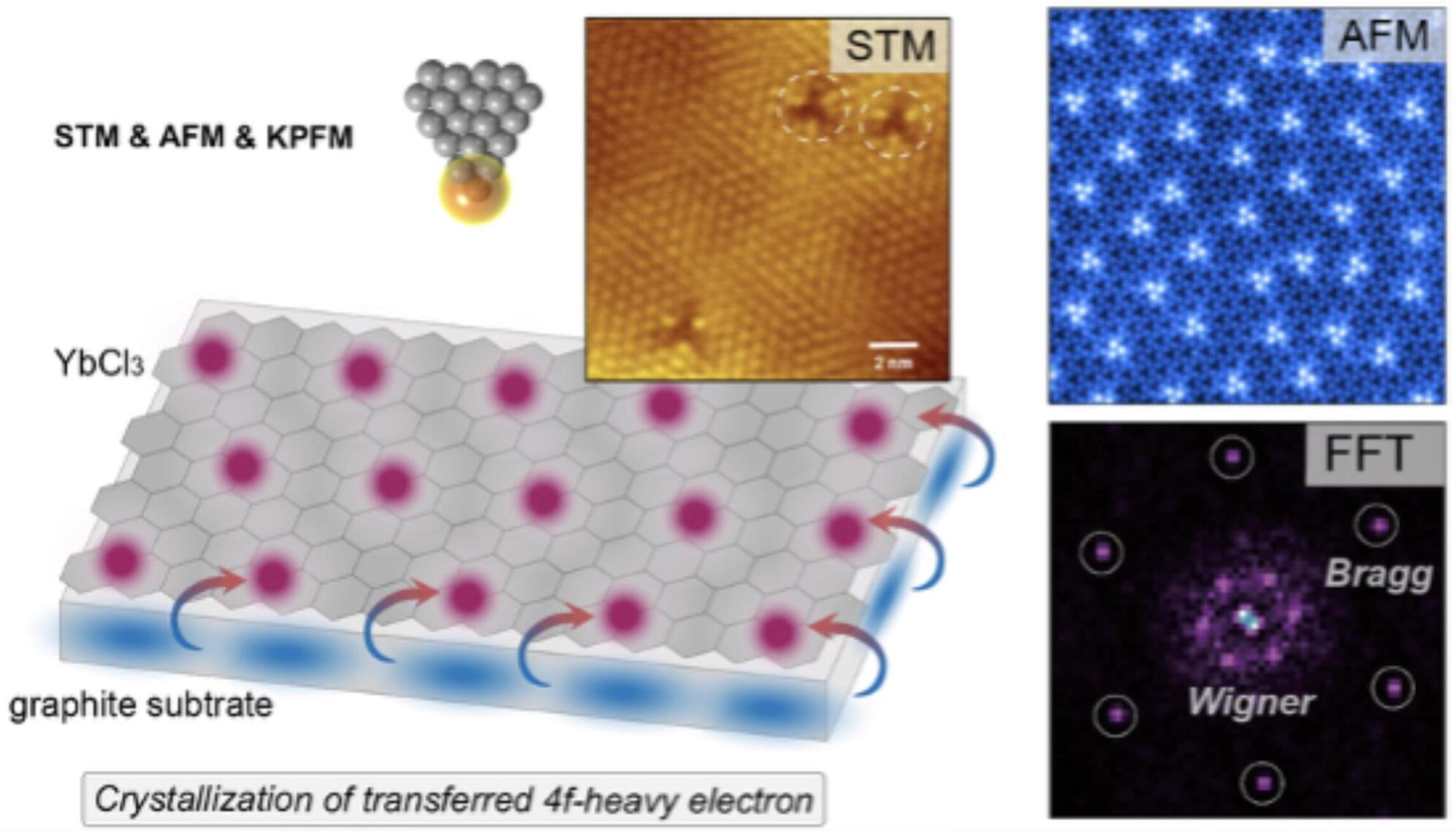

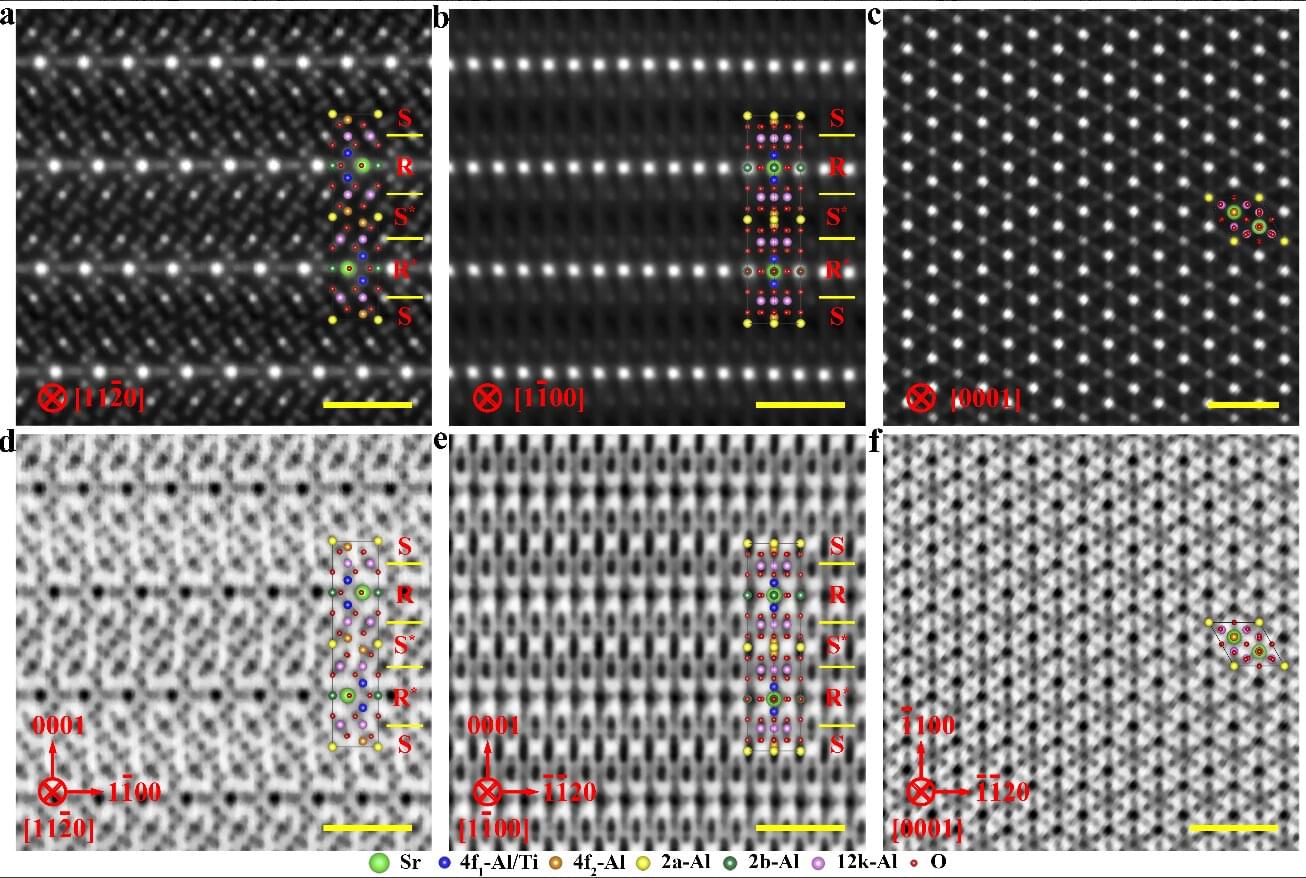

In some solid materials under specific conditions, mutual Coulomb interactions shape electrons into many-body correlated states, such as Wigner crystals, which are essentially solids made of electrons. So far, the Wigner crystal state remains sensitive to various experimental perturbations. Uncovering their internal structure and arrangement at the atomic scale has proven more challenging.

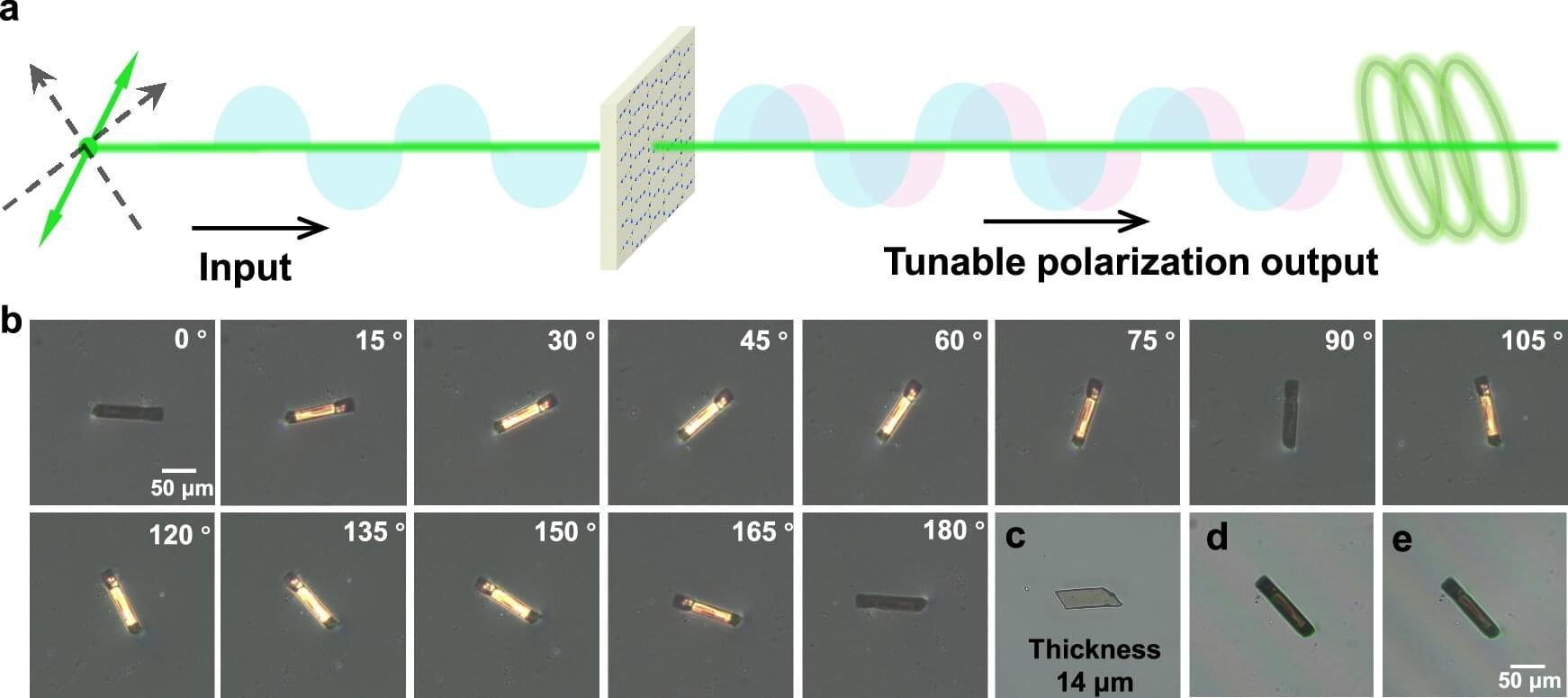

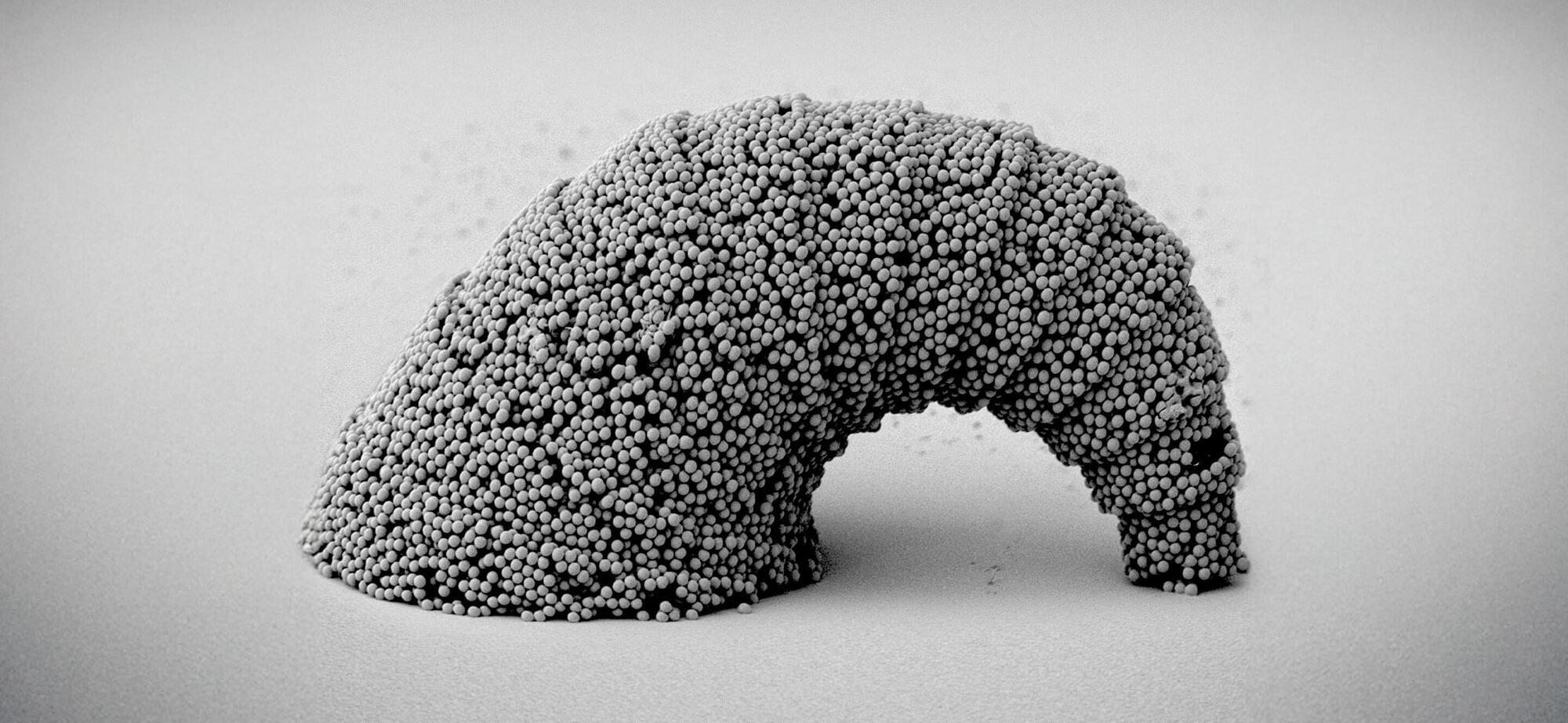

Researchers at Fudan University have introduced a new approach to study the Wigner crystal state in strongly correlated two-dimensional (2D) systems. They successfully made sub-unit-cell resolution images of the Wigner crystalline state in a carefully engineered material comprised of a single atomic layer of ytterbium chloride (YbCl₃) stacked on graphite.

The research is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.