Two recent collaborations between mathematicians and DeepMind demonstrate the potential of machine learning to help researchers generate new mathematical conjectures.

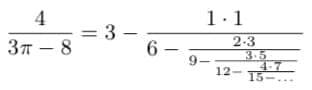

Fundamental constants like e and π are ubiquitous in diverse fields of science, including physics, biology, chemistry, geometry, and abstract mathematics. Nevertheless, for centuries new mathematical formulas relating fundamental constants are scarce and are usually discovered sporadically by mathematical intuition or ingenuity.

Our algorithms search for new mathematical formulas. The community can suggest proofs for the conjectures or even propose or develop new algorithms. Any new conjecture, proof, or algorithm suggested will be named after you.

It may look like a bizarre bike helmet, or a piece of equipment found in Doc Brown’s lab in Back to the Future, yet this gadget made of plastic and copper wire is a technological breakthrough with the potential to revolutionize medical imaging. Despite its playful look, the device is actually a metamaterial, packing in a ton of physics, engineering, and mathematical know-how.

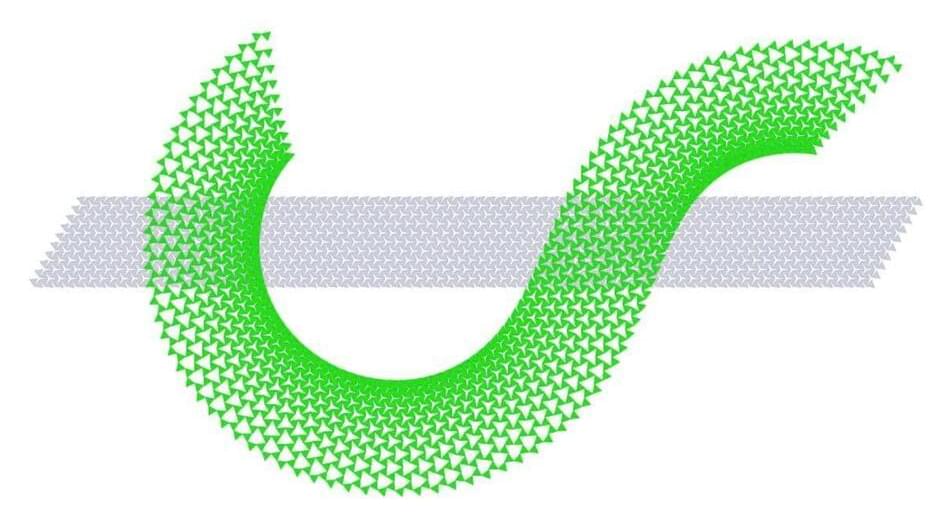

It was developed by Xin Zhang, a College of Engineering professor of mechanical engineering, and her team of scientists at BU’s Photonics Center. They’re experts in metamaterials, a type of engineered structure created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature. Metamaterials, for instance, can bend, absorb, or manipulate waves—such as electromagnetic waves, sound waves, or radio waves. Each unit cell, also called a resonator, is typically arranged in a repeating pattern in rows and columns; they can be designed in different sizes and shapes, and placed at different orientations, depending on which waves they’re designed to influence.

Metamaterials can have many novel functions. Zhang, who is also a professor of electrical and computer engineering, biomedical engineering, and materials science and engineering, has designed an acoustic metamaterial that blocks sound without stopping airflow (imagine quieter jet engines and air conditioners) and a magnetic metamaterial that can improve the quality of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines used for medical diagnosis.

Can you crumple up two sheets of paper the exact same way? Probably not—the very flexibility that lets flexible structures from paper to biopolymers and membranes undergo many types of large deformations makes them notoriously difficult to control. Researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology, Universiteit van Amsterdam, and Universiteit Leiden have shed new light on this fundamental challenge, demonstrating that new physical theories provide precise predictions of the deformations of certain structures, as recently published in Nature Communications.

In the paper, Michael Czajkowski and D. Zeb Rocklin from Georgia Tech, Corentin Coulais from Universiteit van Amsterdam, and Martin van Hecke of AMOLF and Universiteit Leiden approach a highly studied exotic elastic material, uncover an intuitive geometrical description of the pronounced—or nonlinear—soft deformations, and show how to activate any of these deformations on-demand with minimal inputs. This new theory reveals that a flexible mechanical structure is governed by some of the same math as electromagnetic waves, phase transitions, and even black holes.

“So many other systems struggle with how to be strong and solid in some ways but flexible and compliant in others, from the human body and micro-organisms to clothing and industrial robots,” said Rocklin. “These structures solve that problem in an incredibly elegant way that permits a single folding mechanism to generate a wide family of deformations. We’ve shown that a single folding mode can transform a structure into an infinite family of shapes.”

E verything is Code. Immersive [self-]simulacra. We all are waves on the surface of eternal ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness in motion, self-referential creative divine force expressing oneself in an exhaustible variety of forms and patterns throughout the multiverse of universes. “I am” the Alpha, Theta & Omega – the ultimate self-causation, self-reflection and self-manifestation instantiated by mathematical codes and projective fractal geometry.

In my new volume of The Cybernetic Theory of Mind series – The Omega Singularity: Universal Mind & The Fractal Multiverse – we discuss a number of perspectives on quantum cosmology, computational physics, theosophy and eschatology. How could dimensionality be transcended yet again? What is the fractal multiverse? Is our universe a “metaverse” in a universe up? What is the ultimate destiny of our universe? Why does it matter to us? What is the Omega Singularity?

“The methods used to approach it cover, I would say, the whole of mathematics,” said Andrei Yafaev of University College London.

The new paper begins with one of the most basic but provocative questions in mathematics: When do polynomial equations like x3 + y3 = z3 have integer solutions (solutions in the positive and negative counting numbers)? In 1994, Andrew Wiles solved a version of this question, known as Fermat’s Last Theorem, in one of the great mathematical triumphs of the 20th century.

In the quest to solve Fermat’s Last Theorem and problems like it, mathematicians have developed increasingly abstract theories that spark new questions and conjectures. Two such problems, stated in 1989 and 1995 by Yves André and Frans Oort, respectively, led to what’s now known as the André-Oort conjecture. Instead of asking about integer solutions to polynomial equations, the André-Oort conjecture is about solutions involving far more complicated geometric objects called Shimura varieties.

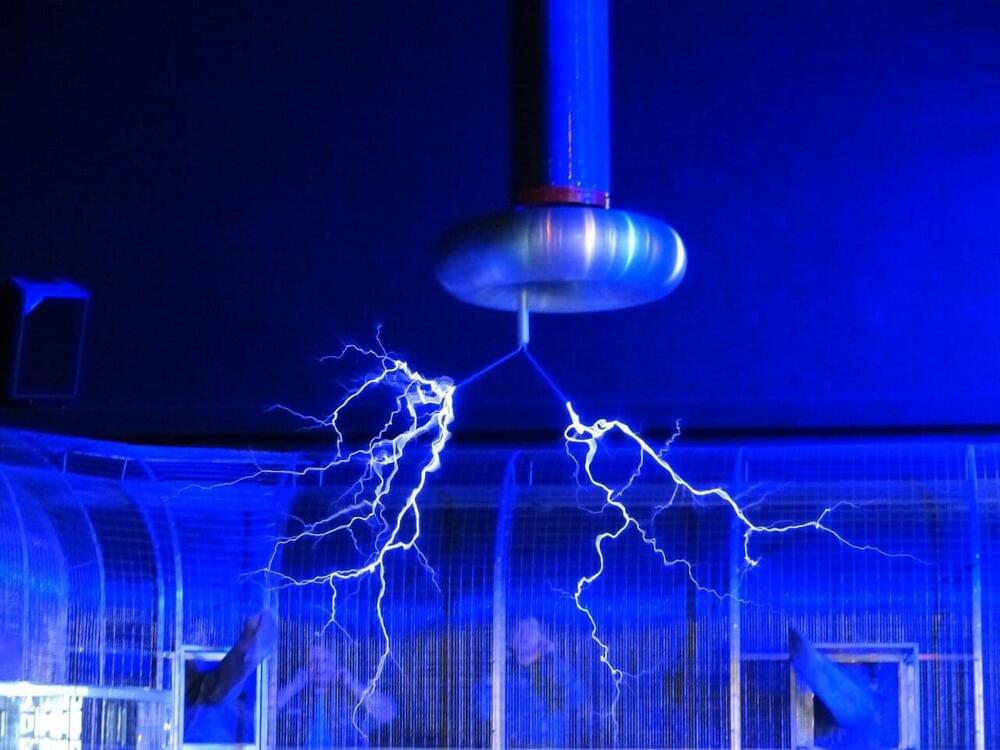

Imagine if we could use strong electromagnetic fields to manipulate the local properties of spacetime—this could have important ramifications in terms of science and engineering.

Electromagnetism has always been a subtle phenomenon. In the 19th century, scholars thought that electromagnetic waves must propagate in some sort of elusive medium, which was called aether. Later, the aether hypothesis was abandoned, and to this day, the classical theory of electromagnetism does not provide us with a clear answer to the question in which medium electric and magnetic fields propagate in vacuum. On the other hand, the theory of gravitation is rather well understood. General relativity explains that energy and mass tell the spacetime how to curve and spacetime tells masses how to move. Many eminent mathematical physicists have tried to understand electromagnetism directly as a consequence of general relativity. The brilliant mathematician Hermann Weyl had especially interesting theories in this regard. The Serbian inventor Nikola Tesla thought that electromagnetism contains essentially everything in our universe.

“It is what I would call a dippy process,” Richard Feynman later wrote. “Having to resort to such hocus-pocus has prevented us from proving that the theory of quantum electrodynamics is mathematically self-consistent.”

Justification came decades later from a seemingly unrelated branch of physics. Researchers studying magnetization discovered that renormalization wasn’t about infinities at all. Instead, it spoke to the universe’s separation into kingdoms of independent sizes, a perspective that guides many corners of physics today.

Renormalization, writes David Tong, a theorist at the University of Cambridge, is “arguably the single most important advance in theoretical physics in the past 50 years.”

Quantum computers could cause unprecedented disruption in both good and bad ways, from cracking the encryption that secures our data to solving some of chemistry’s most intractable puzzles. New research has given us more clarity about when that might happen.

Modern encryption schemes rely on fiendishly difficult math problems that would take even the largest supercomputers centuries to crack. But the unique capabilities of a quantum computer mean that at sufficient size and power these problems become simple, rendering today’s encryption useless.

That’s a big problem for cybersecurity, and it also poses a major challenge for cryptocurrencies, which use cryptographic keys to secure transactions. If someone could crack the underlying encryption scheme used by Bitcoin, for instance, they would be able to falsify these keys and alter transactions to steal coins or carry out other fraudulent activity.