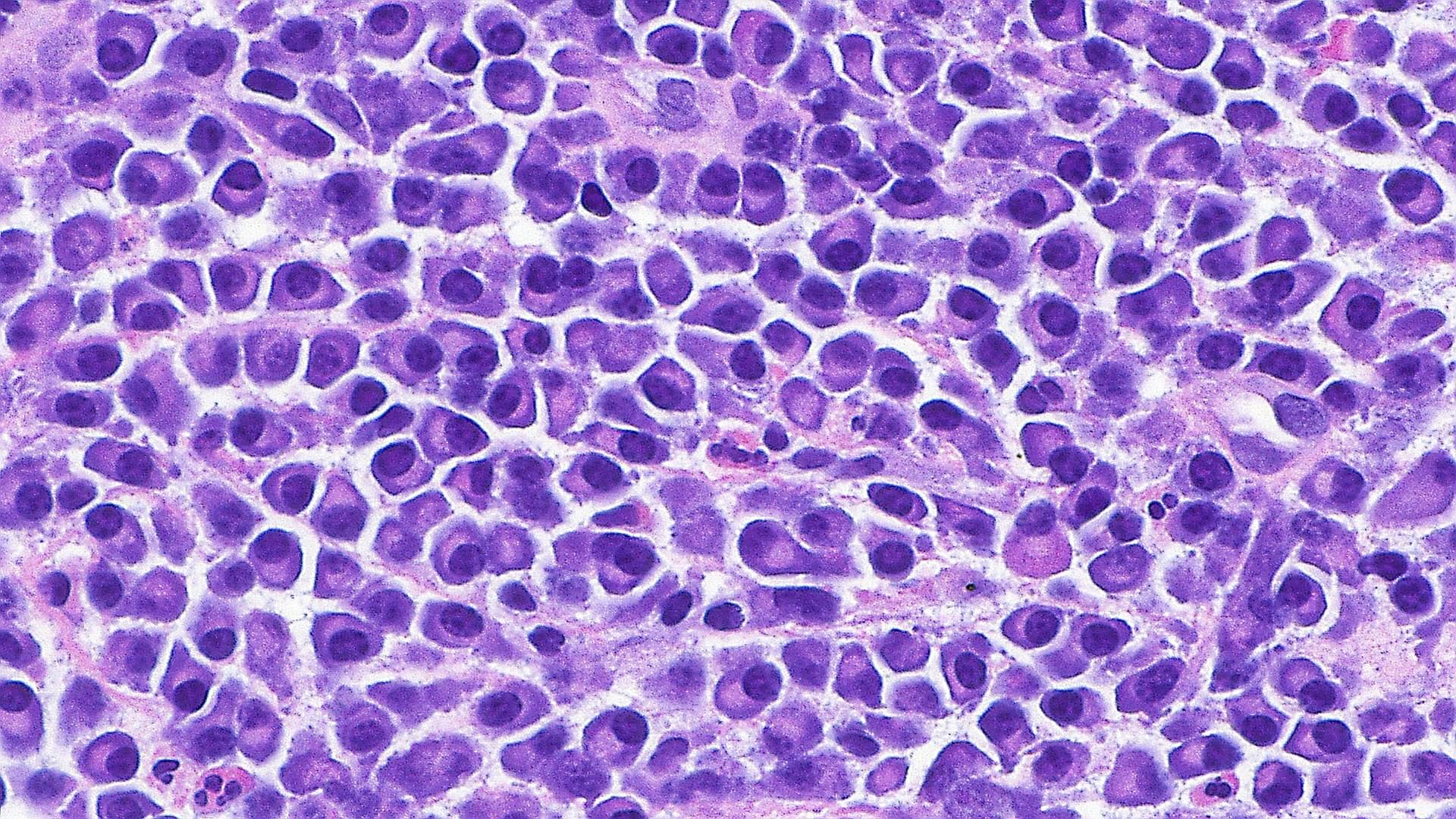

Using the same math deployed in string theory, network scientists have solved a standing mystery about the brain’s architecture.

For more than a century, scientists have wondered why physical structures like blood vessels, neurons, tree branches, and other biological networks look the way they do. The prevailing theory held that nature simply builds these systems as efficiently as possible, minimizing the amount of material needed. But in the past, when researchers tested these networks against traditional mathematical optimization theories, the predictions consistently fell short.

The problem, it turns out, was that scientists were thinking in one dimension when they should have been thinking in three. “We were treating these structures like wire diagrams,” Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) physicist Xiangyi Meng, Ph.D., explains. “But they’re not thin wires, they’re three-dimensional physical objects with surfaces that must connect smoothly.”

This month, Meng and colleagues published a paper in the journal Nature showing that physical networks in living systems follow rules borrowed from an unlikely source: string theory, the exotic branch of physics that attempts to explain the fundamental structure of the universe.

Physicists like Sean Carroll propose not only that quantum mechanics is not only a valuable way of interpreting the world, but actually describes reality, and that the wave function – the centre equation of quantum mechanics – describes a real object.

But, in this article, philosophers Raoni Arroyo and Jonas R. Becker Arenhart argue that the case for wave function realism is deeply confused. While it is a useful component within quantum theory, this alone doesn’t justify treating it as literally real.

Tap the link to read more.

Physicists like Sean Carroll argue not only that quantum mechanics is not only a valuable way of interpreting the world, but actually describes reality, and that the central equation of quantum mechanics – the wave function – describes a real object in the world. But philosophers Raoni Arroyo and Jonas R. Becker Arenhart warn that the arguments for wave-function realism are deeply confused. At best, they show only that the wave function is a useful element inside the theoretical framework of quantum mechanics. But this goes no way whatsoever to showing that this framework should be interpreted as true or that its elements are real. The wavefunction realists are confusing two different levels of debate and lack any justification for their realism. The real question is: does a theory need to be true to be useful?

Quantum mechanics is probably our most successful scientific theory. So, if one wants to know what the world is made of, or how the world looks at the fundamental level, one is well-advised to search for the answers in this theory. What does it say about these problems? Well, that is a difficult question, with no single answer. Many interpretative options arise, and one quickly ends up in a dispute about the pros and cons of the different views. Wavefunction realists attempt to overcome those difficulties by looking directly at the formalism of the theory: the theory is a description of the behavior of a mathematical entity, the wavefunction, so why not think that quantum mechanics is, fundamentally, about wavefunctions? The view that emerges is, as Alyssa Ney puts it, that.

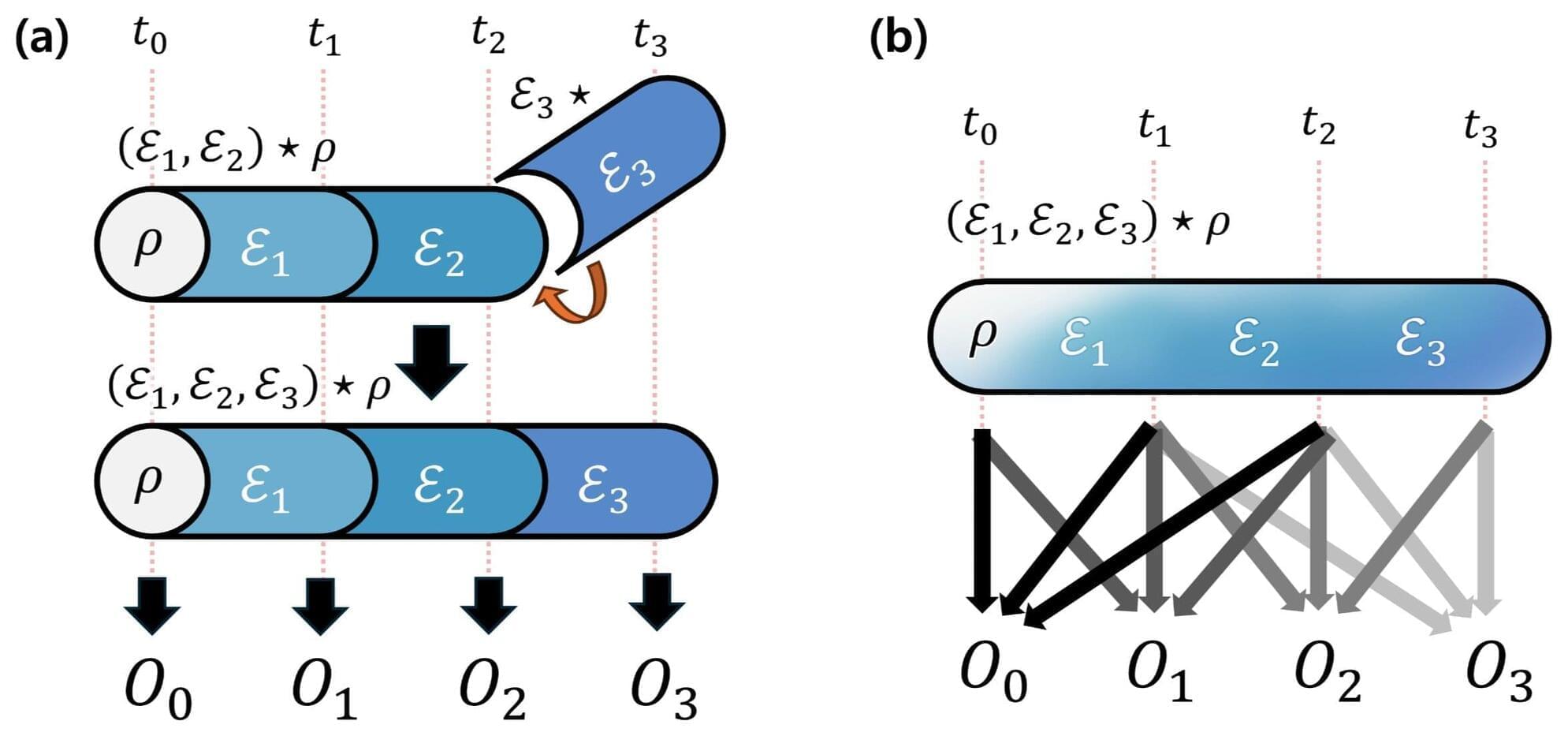

Quantum mechanics and relativity are the two pillars of modern physics. However, for over a century, their treatment of space and time has remained fundamentally disconnected. Relativity unifies space and time into a single fabric called spacetime, describing it seamlessly. In contrast, traditional quantum theory employs different languages: quantum states (density matrix) for spatial systems and quantum channels for temporal evolution.

A recent breakthrough by Assistant Professor Seok Hyung Lie from the Department of Physics at UNIST offers a way to describe quantum correlations across both space and time within a single, unified framework. Assistant Professor Lie is first author, with Professor James Fullwood from Hainan University serving as the corresponding author. Their collaboration creates new tools that could significantly impact future studies in quantum science and beyond. The study has been published in Physical Review Letters.

In this study, the team developed a new theoretical approach that treats the entire timeline as one quantum state. This concept introduces what they call the multipartite quantum states over time. In essence, it allows us to describe quantum processes at different points in time as parts of a single, larger quantum state. This means that both spatially separated systems and systems separated in time can be analyzed using the same mathematical language.

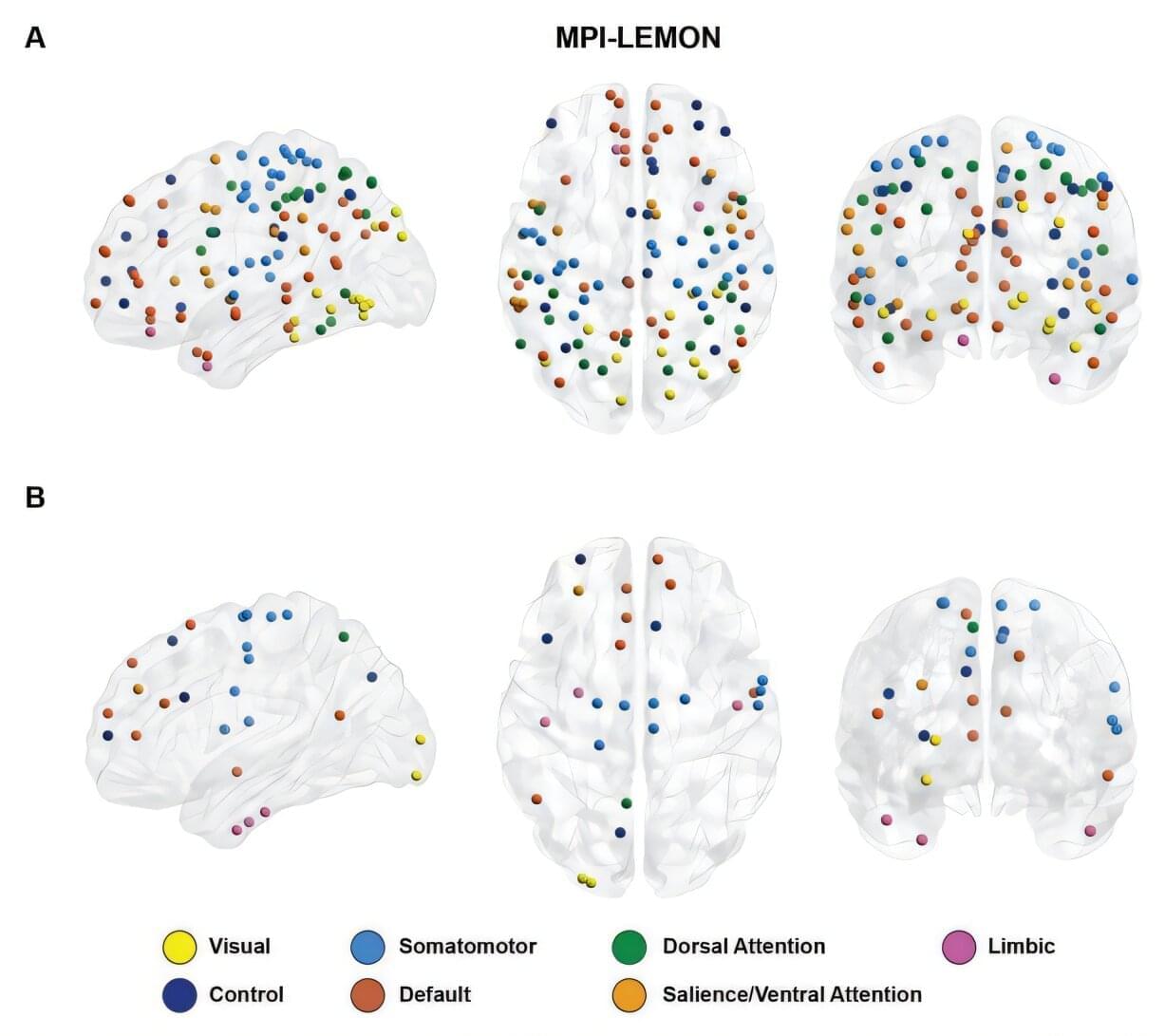

It is a central question in neuroscience to understand how different regions of the brain interact, how strongly they “talk” to each other. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences Leipzig, Germany, the Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Chennai, India, and colleagues demonstrate how mathematical techniques from topological data analysis (TDA) can provide a new, multiscale perspective on brain connectivity. The study was published in the journal Patterns.

With the rise of large neuroimaging datasets, scientists now work with detailed maps of brain connectivity—network representations that show how hundreds of brain regions fluctuate and coordinate their activity over time. But making sense of these enormous networks poses a challenge: What patterns matter? Which changes signal healthy aging, and which reflect differences associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)?

The study introduces a mathematical innovation that helps answer precisely these questions. Researchers applied persistent homology, a tool from topological data analysis (TDA), to detect how brain connectivity reorganizes during healthy aging and in ASD.

One of the world’s foremost philosophers of physics, Maudlin is Professor of Philosophy at NYU and Founder and Director of the John Bell Institute for the Foundations of Physics.

He is a member of the “Foundational Questions Institute” of the Académie Internationale de Philosophie des Sciences and is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, and author of ‘The Metaphysics Within Physics’, ‘Truth and Paradox: Solving the Riddles’ and ‘Quantum Non-Locality and Relativity’

Tap the link to watch his full talk now: https://iai.tv/video/tim-maudlin-why-imaginary-numbers-are-c…um-physics

Why do imaginary numbers appear at the foundation of quantum mechanics? This question, which puzzled even great physicists like Eugene Wigner, opens up deeper issues about what it means to explain features of the mathematical formalism used in physical theory. Join philosopher of science Tim Maudlin as he explores that question through the lens of quantum dynamics, arguing that the appearance of complex numbers in Schrödinger’s equation is not arbitrary, but motivated by the need for a particular kind of wave-like structure in fundamental dynamics.

Einstein never liked the idea that nature is uncertain and he once said “does that mean the Moon is not there when I am not looking at it”. He believed we live in an orderly Universe which is fundamentally rational and that there should always be a reason why thing happen. But there is a way to have the objective Universe of Einstein and the uncertainty of quantum physics and that is by explaining quantum mechanics as the physics of ‘time’ with the future as an emergent property.

In this radical theory the mathematics of quantum mechanics represents the physics of ‘time’ as a physical process with classical physics representing process over a period of time as in Newton’s differential equations. This is a process formed by the spontaneous absorption and emission of light photon energy. This forms a continuous process of energy exchange that forms the ever changing world of our everyday life.

The Universe is a continuum with the future coming into existence photon by photon with each new photon electron coupling or dipole moment. This forms the movement of positive and negative charge with the continuous flow of electromagnetic fields.

Consciousness in the form of electrical activity in the brain is the most advanced part of this process and can therefore comprehend this process as ‘time’. With a past that has gone forever and a future that is always uncertain in the form of a probability function or quantum wave particle function that is explained mathematically by Schrödinger’s wave equation Ψ. Therefore each individual is in the centre of their own reference frame as an interactive part of this process. With their own time line from the past into the future being able to look back in time in all directions at the beauty of the stars! It is this personalization of the brain being in ‘the moment of now’ in the center of its own reference frame that gives us the concept of ‘mind’ with each one of us having our own personal view of the beauty and uncertainty of life.

It is not that there is uncertainty if the Moon is there or not if nobody looks. It is that the physical act of looking will form new light photon oscillations or vibrations relative to the actions of the observer in a continuous flow of cause and effect. The wave particle duality of light is acting like the bits or zeros and ones of a computer. This forms an interactive process continuously forming a blank canvas that we can interact with turning the possible into the actual! Any observation of the Moon will be over a period of time with the wave nature of light explaining diffraction, interference, reflection and refraction. But the particle nature of light the ‘photon’ will only come into existence when the light comes in contact with the lenses and mirrors of the telescope being used. And finally with new photons be formed in the eye of the observer the uncertainty of the observation will be completed using both the wave and particle nature of light!

What we see in our everyday life as an uncertain future is formed by a physical process that at the smallest scale is represented mathematically by Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle ∆×∆p×≥h/4π with the Planck constant ħ=h/2π being a constant of action in the dynamics geometry of space and time! This theory takes quantum potential, electrical potential and gravitational potential and combines them into one universal process. That explains why we all have a potential future in our everyday life that is always uncertain. This is done by making the future an emergent property energy ∆E slows the rate that time ∆t flows creating a future relative to the energy and momentum of each object or life form. For in this theory creation is truly in the hand and eye of the beholder with an objective reality in the form of a dynamic interactive process that forms an infinity of possibilities. Please share and subscribe it will help the promotion of this theory!

Quantum information theory is a field of study that examines how quantum technologies store and process information. Over the past decades, researchers have introduced several new quantum information frameworks and theories that are informing the development of quantum computers and other devices that operate leveraging quantum mechanical effects.

These include so-called resource theories, which outline the transformations that can take place in quantum systems when only a limited number of operations are allowed.

In 2008, two scientists at Imperial College London introduced what they termed the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma, a mathematical theorem that describes how well quantum states can be distinguished from one another. In this generalized setting, one typically considers multiple identical copies of a specific state (the null hypothesis) and tests them against a composite alternative hypothesis, i.e., a set of states (e.g., resource-free states).