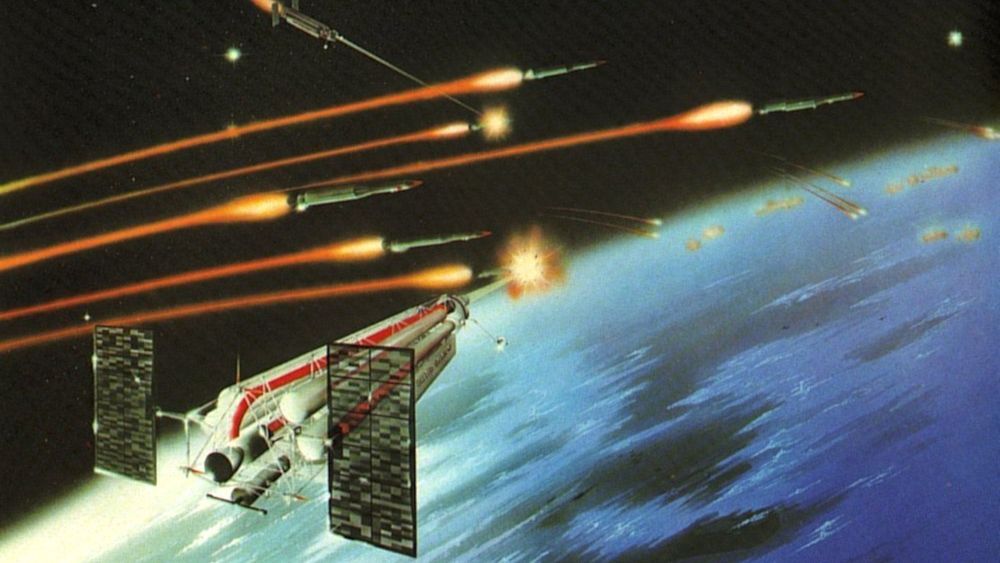

The U.S. Missile Defense Agency is looking for information on a 1,000 kW-class electrically-pumped laser for defending the United States, its deployed forces, allies, and friends against all ranges of enemy ballistic missiles in all phases of flight.

The post on the federal business opportunities website is asking industry for information on a capability to demonstrate a 1,000 kW-class electrically-pumped laser in the 2025–26 timeframe.

Missile Defense Agency does not provide a specific platform or strategic mission at this time. The proposed ground demonstrator laser system would be designed to have technology maturation and lightweight engineering paths to potential future platforms.