But what if our biological makeup limits how creative we can be? Maybe the timing of the clock that governs our introspections forces our intuitive periods—or the times of uncertainty—to be too brief. Could we use our quantum technologies to extend the wavelike processing inside our brains? I am here inspired by Aldous Huxley, who suggested in his famous book, The Doors of Perception, that drugs could alter our consciousness, revealing true reality. But rather than using drugs, I envision quantum chips designed to suppress the “noise” that induces introspection, allowing a longer interference period for our intuitive thoughts to develop. This has the potential to be far more potent than what Huxley could ever have imagined.

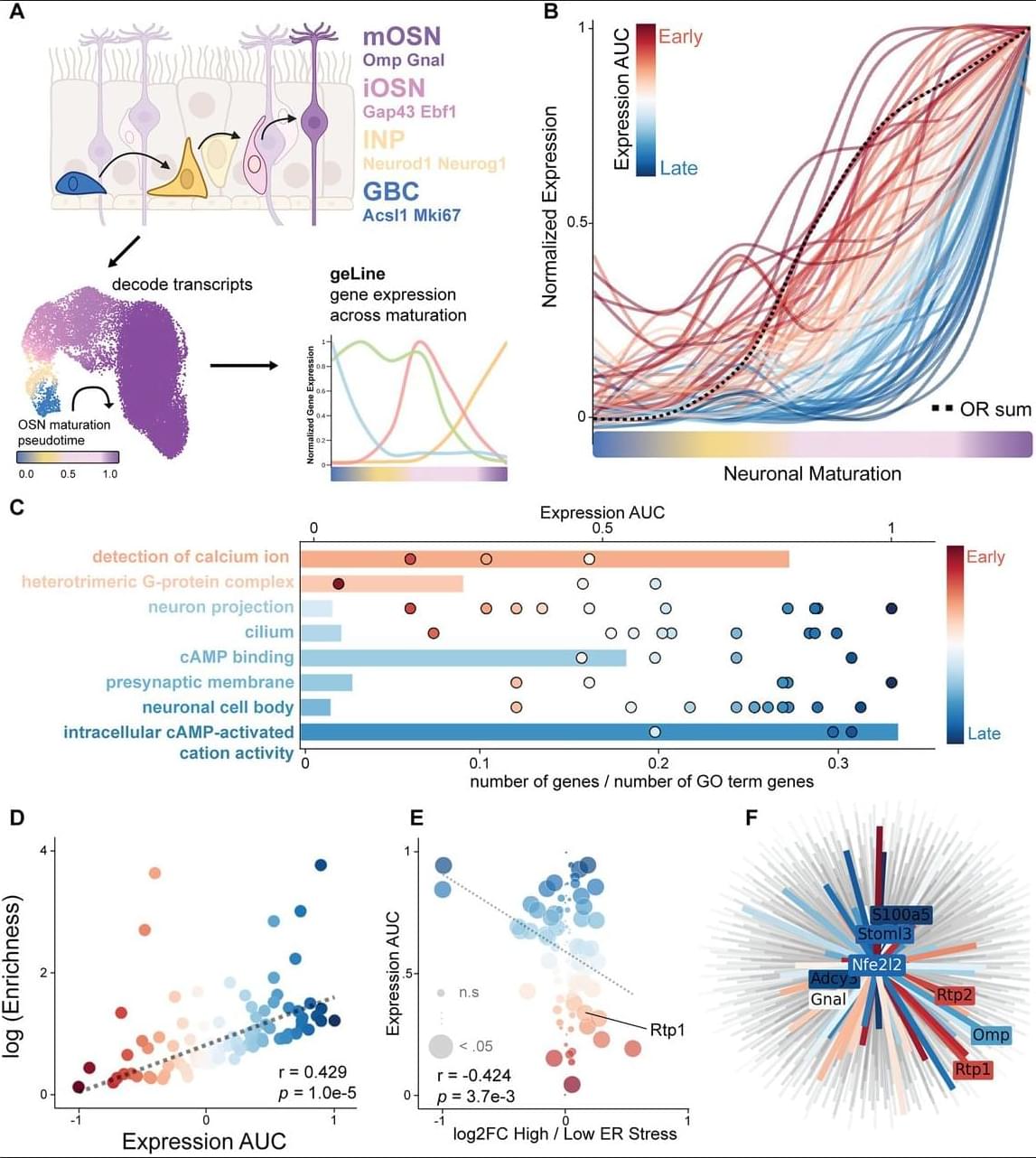

For my idea to work, we would first have to understand where and how these superpositions are stored and manipulated in the brain. The British physicist Roger Penrose, PhD, has speculated that this occurs within microtubules, which are dynamic, hollow, rod-like components of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton that are responsible for things such as intercellular transport. Despite some circumstantial evidence, we do not have a strong reason to believe that microtubules are capable of quantum interference, but they are certainly worth further investigation. Once we understand how our brain uses quantum effects, we could then design a quantum chip that interfaces with the relevant biological components. Theoretically, the device would be able to upload superposition states to store them for longer periods and shield them from collapse, helping us to enhance our creative wavelike thinking.

One wonders what kind of power would be unleashed by doing this. I imagine the change would not be purely quantitative, so that we merely become faster calculators or quicker problem solvers, although even that would be amazing. Instead, I think the change could be qualitative, expanding our perception into a completely different realm, effectively creating a new species. We might theoretically become more powerful than modern humans, just as we currently are with respect to other apes. Quantum-enhanced humans would see further domains of reality that would otherwise remain hidden forever from us ordinary humans.