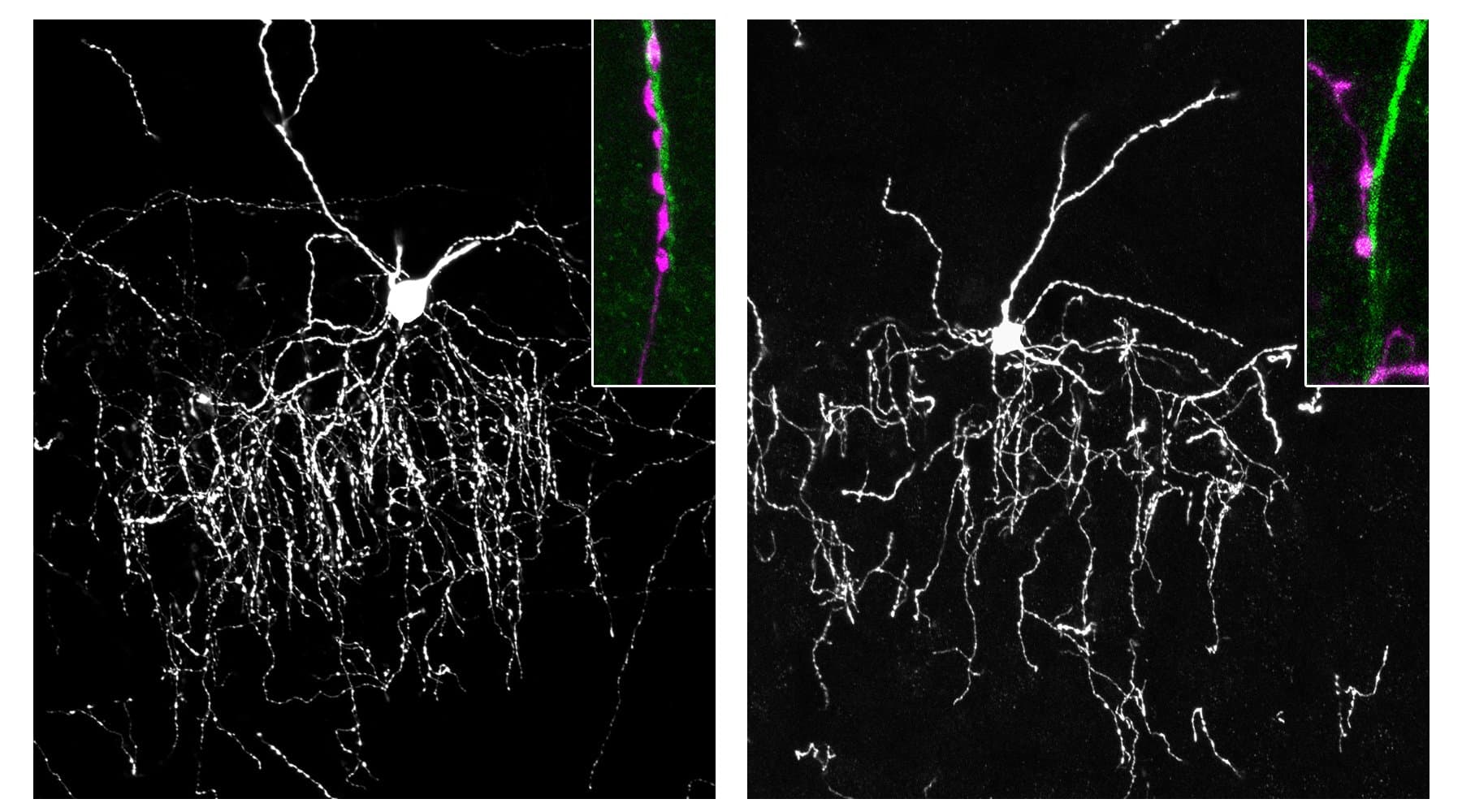

A new study published in Neuropsychopharmacology suggests that the use of oral contraceptives may influence how the brain regulates fear responses in safe environments. The research indicates that women who use birth control pills, particularly those with higher doses of synthetic estrogen, may experience elevated fear in safe contexts compared to women who have never used hormonal contraception. The findings also imply that these alterations in fear processing could persist for a significant period after an individual stops taking the medication.

Anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder are nearly twice as prevalent in women as they are in men. Biological factors likely contribute to this disparity, with sex hormones acting as potential mediators. Specifically, the hormone estradiol plays a significant role in how the brain manages fear and memory.

Effective fear regulation requires the ability to distinguish between a threat and a safety signal based on the surrounding environment. For example, seeing a snake in a forest might require a fear response, while seeing a snake in a zoo enclosure should not. This process is known as contextual fear regulation.