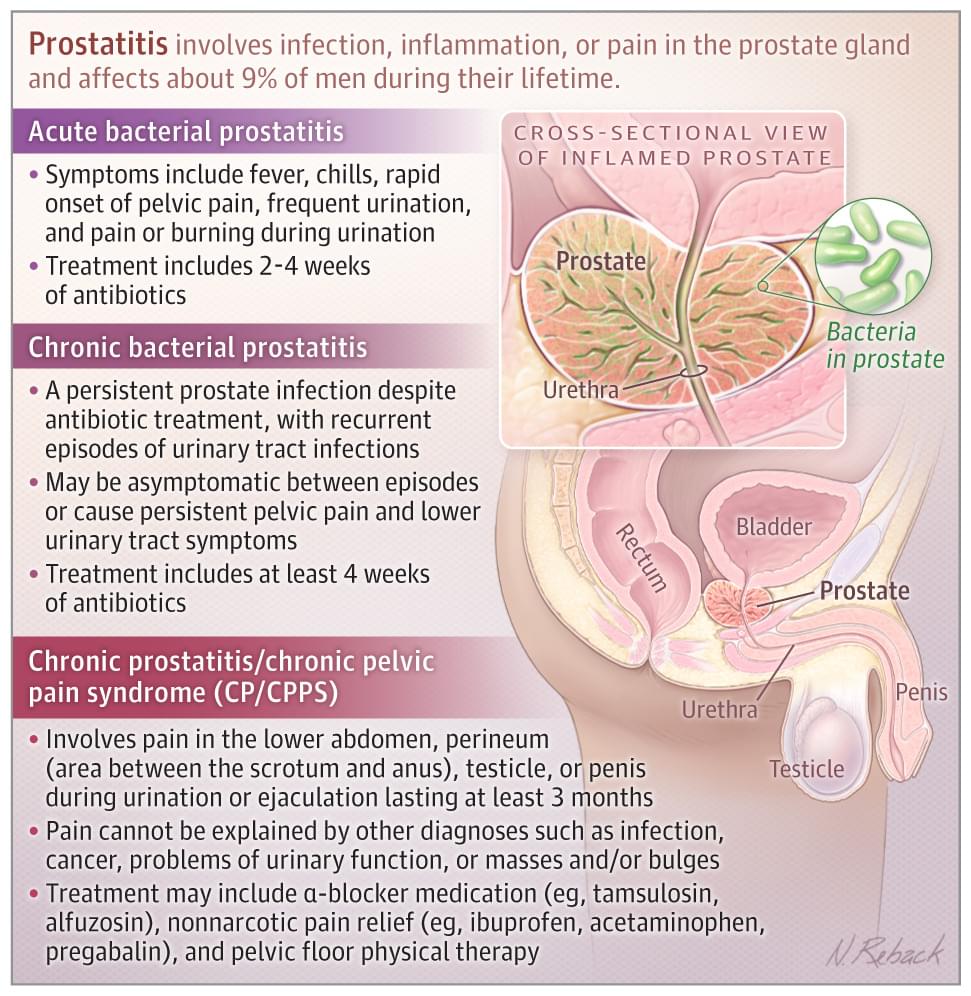

📄 This JAMA Patient Page describes the types of prostatitis and its risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment.

Prostatitis involves infection, inflammation, or pain in the prostate gland and affects about 9% of men during their lifetime.

Patients with acute prostatitis typically have fever, chills, pelvic pain, sudden onset of frequent urination, and pain or burning during urination.

📄 Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment of CP/CPPS

Approximately 267 000 men in the US are diagnosed with CP/CPPS each year. Risk increases after age 50 years. Although other risk factors for CP/CPPS are unclear, men with CP/CPPS are more likely to have chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome and higher rates of depression, anxiety, and panic disorder than unaffected men.