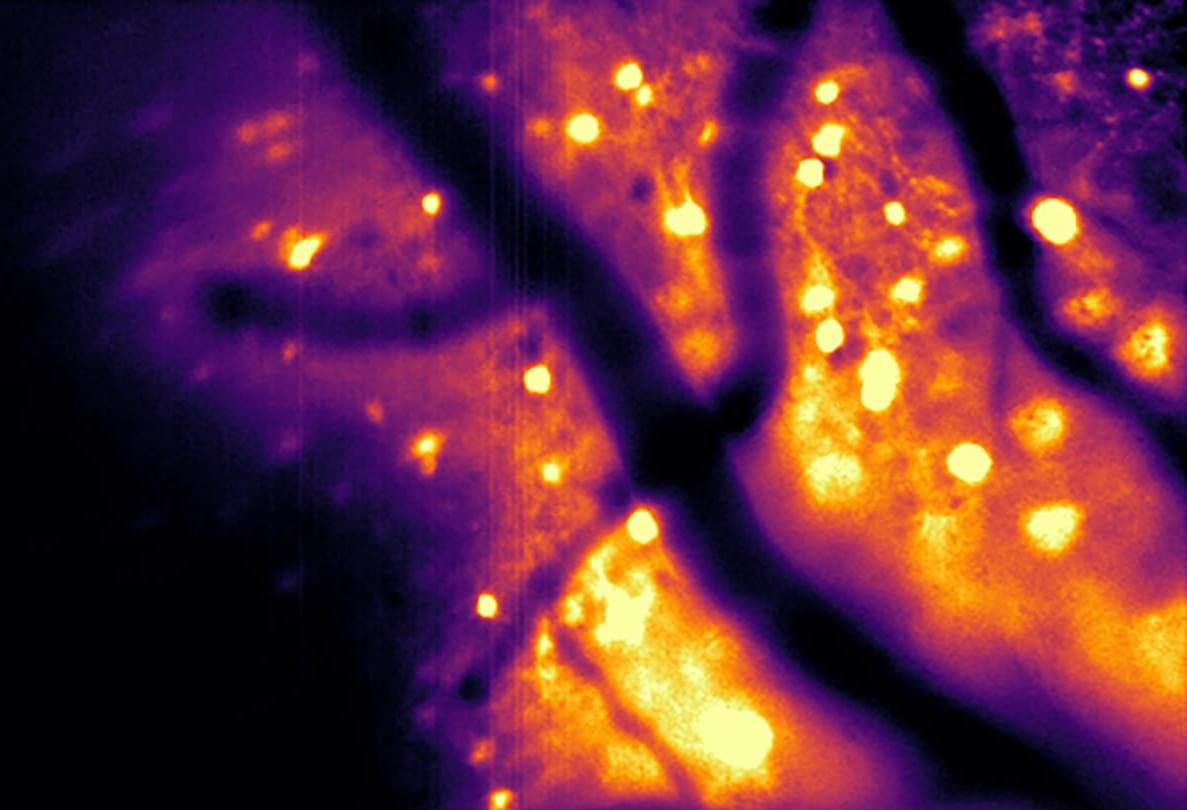

A decade ago, a group of scientists had the literally brilliant idea to use bioluminescent light to visualize brain activity.

“We started thinking: ‘What if we could light up the brain from the inside?’” said Christopher Moore, a professor of brain science at Brown University. “Shining light on the brain is used to measure activity — usually through a process called fluorescence — or to drive activity in cells to test what role they play. But shooting lasers at the brain has down sides when it comes to experiments, often requiring fancy hardware and a lower rate of success. We figured we could use bioluminescence instead.”

With a major grant from the National Science Foundation, the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science launched in 2017 based on collaborations between Moore (associate director of the Carney Institute), Diane Lipscombe (the institute’s director), Ute Hochgeschwender (at Central Michigan University) and Nathan Shaner (at the University of California San Diego).

The scientists’ goal was to develop and disseminate neuroscience tools based on giving nervous system cells the ability to make and respond to light.

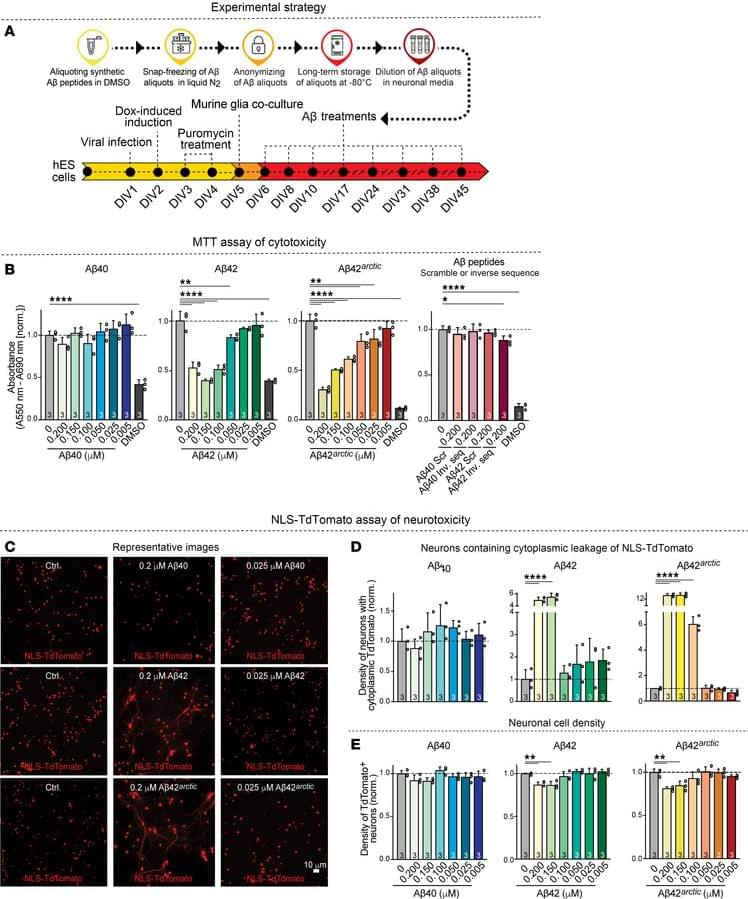

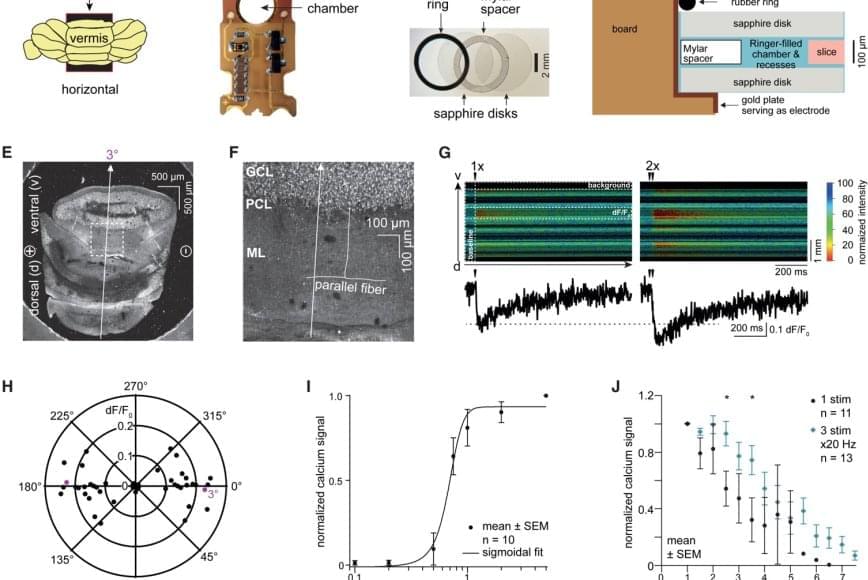

In a study published in Nature Methods, the team described a bioluminescence tool it recently developed. Called the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor — or “CaBLAM,” for short — the tool captures single-cell and subcellular activity at high speeds and works well in mice and zebrafish, allowing multi-hour recordings and removing the need for external light.

More said that Shaner, an associate professor in neuroscience and in pharmacology at U.C. San Diego, led the development of the molecular device that became CaBLAM: “CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created,” Moore said. “It lives up to its name.”

Measuring ongoing activity of living brain cells is essential to understanding the functions of biological organisms, Moore said. The most common current approach uses imaging with fluorescence-based genetically encoded calcium-ion indicators.