A discovery from Australian researchers could lead to better treatment for children with neuroblastoma, a cancer that currently claims 9 out of 10 young patients who experience recurrence. The team at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia, found a drug combination that can bypass the cellular defenses these tumors develop that lead to relapse.

In findings made in animal models and published today in Science Advances, Associate Professor David Croucher and his team have shown that a drug already approved for other cancers can trigger neuroblastoma cell death through alternative pathways when the usual routes become blocked. This discovery could lead to better treatment strategies for children whose cancers have stopped responding to standard chemotherapy.

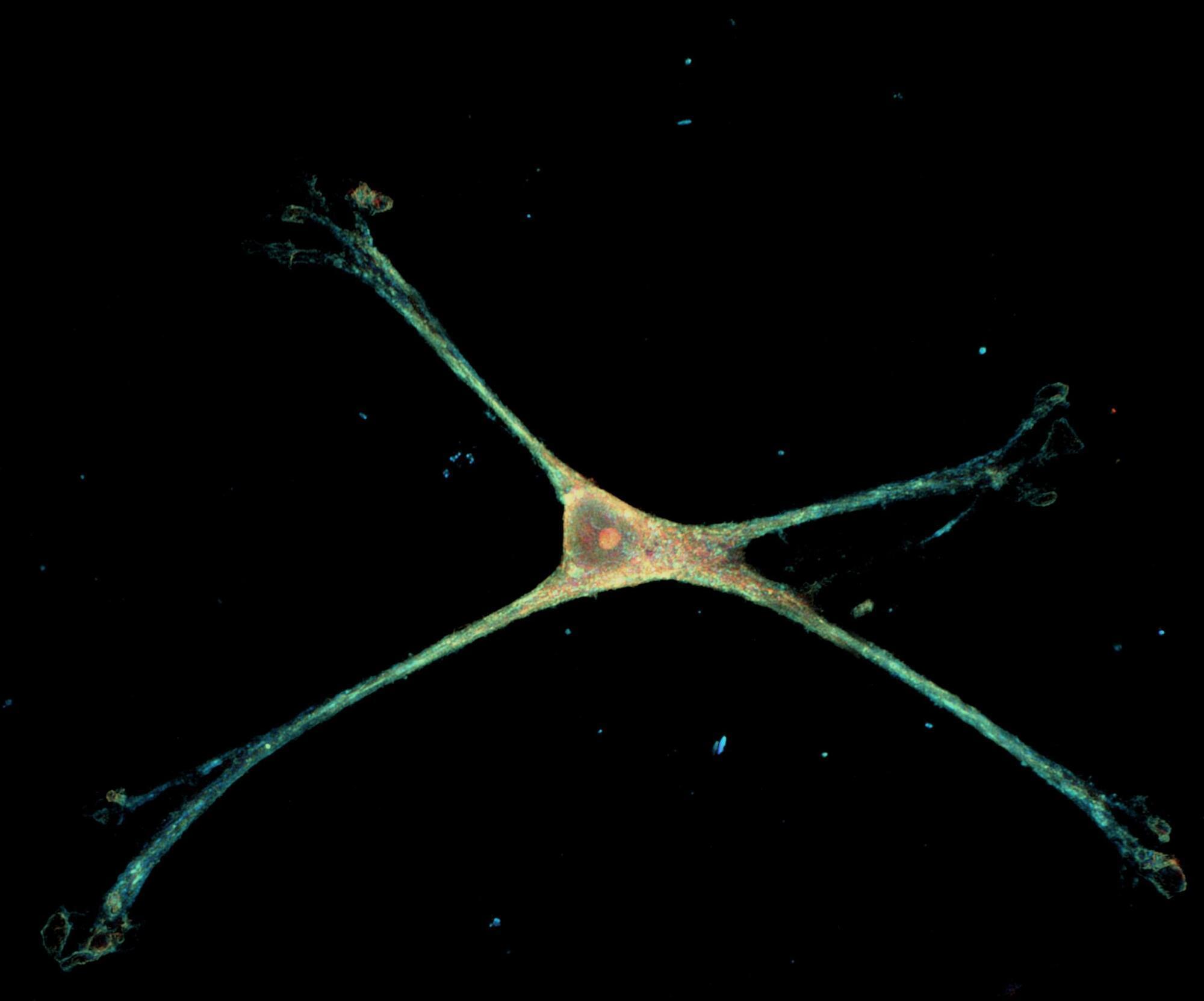

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid tumor in children outside the brain, developing from nerve cells in the adrenal glands above the kidneys or along the spine, chest, abdomen or pelvis. It is typically diagnosed in children under 2 years old. While those with low-risk disease have excellent outcomes, around half of patients are diagnosed with high-risk neuroblastoma—an aggressive form where tumors have already spread. Of these high-risk patients, 15% don’t respond to initial treatment, and half of those who do respond will see their cancer return.