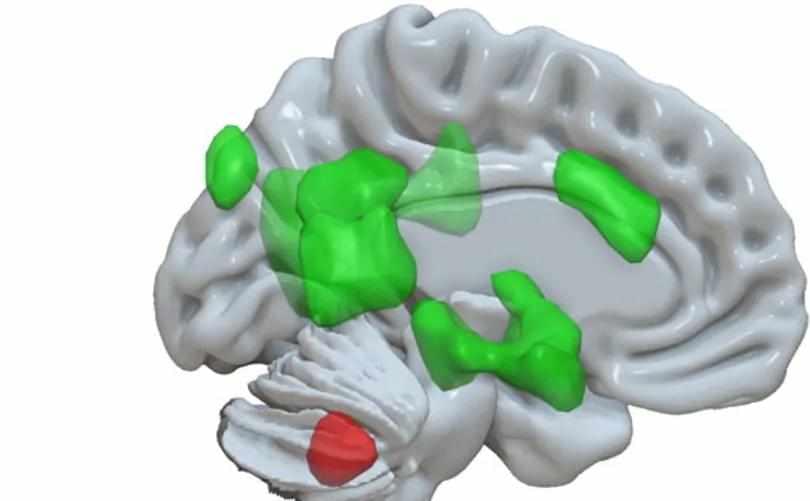

Glia, a non-excitable cell type once considered merely as the connective tissue between neurons, is nowadays acknowledged for its essential contribution to multiple physiological processes including learning, memory formation, excitability, synaptic plasticity, ion homeostasis, and energy metabolism. Moreover, as glia are key players in the brain immune system and provide structural and nutritional support for neurons, they are intimately involved in multiple neurological disorders. Recent advances have demonstrated that glial cells, specifically microglia and astroglia, are involved in several neurodegenerative diseases including Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). While there is compelling evidence for glial modulation of synaptic formation and regulation that affect neuronal signal processing and activity, in this manuscript we will review recent findings on neuronal activity that affect glial function, specifically during neurodegenerative disorders. We will discuss the nature of each glial malfunction, its specificity to each disorder, overall contribution to the disease progression and assess its potential as a future therapeutic target.

Glia are non-neuronal cells of the nervous system which do not generate electrical impulses yet communicate via other means such as calcium signals. Due to their lack of electrical activity, it was previously assumed that glial cells primarily functioned as “nerve-glue” (Virchow, 1860) and performed house-keeping functions for neurons; however, this concept has shifted due to recent findings showing glia are key components in many neuronal functions that go far beyond housekeeping (Araque et al., 1999; Buskila et al., 2019a).

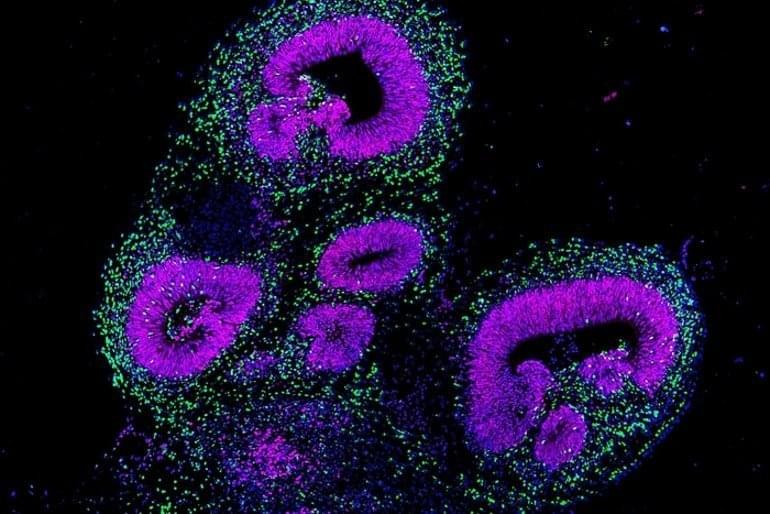

Glial cells are categorized into two main groups; macroglia, which includes astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, NG2-glia and ependymal cells, and microglia which are the resident phagocytes of the central nervous system (CNS). Each population of glial cells is specialized for a particular function in the central or peripheral nervous system (García-Cabezas et al., 2016), and normal brain function depends on the interplay between neurons and the various types of glial cells. In this review, we will focus on astrocytes and microglia.