A newly discovered collection of neurons suggests the brain and heart communicate to trigger a neuroimmune response after a heart attack, which may pave the way for new therapies

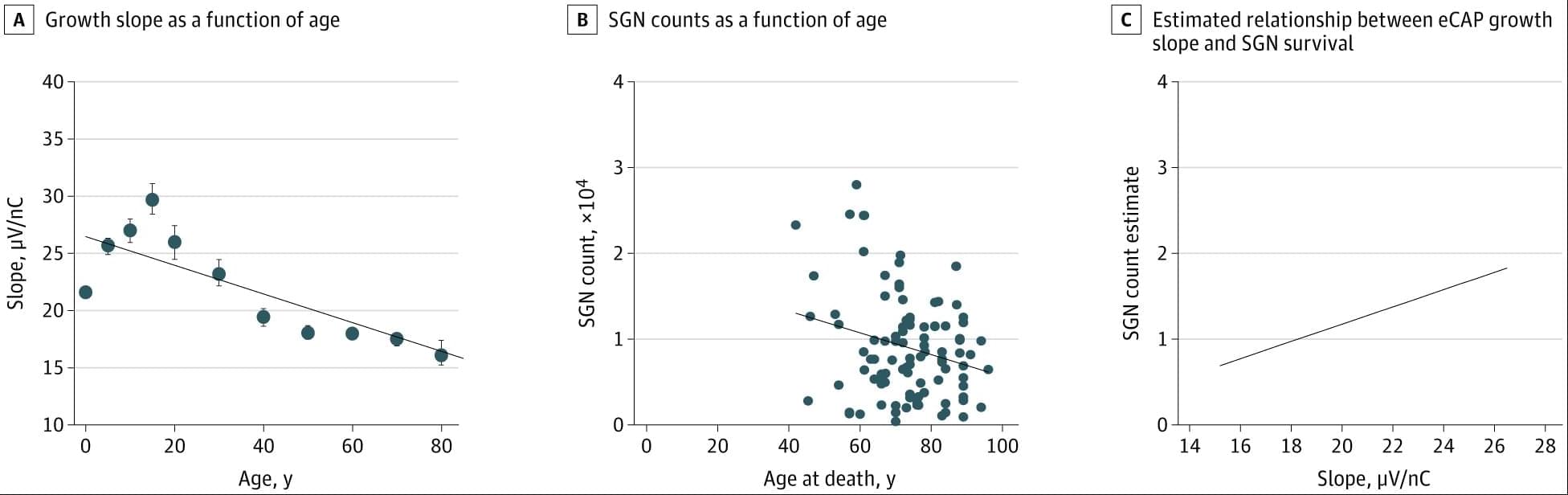

Model-based analysis of ECAPs in CochlearImplant users showed stronger auditory nerve responses and plasticity in younger recipients, highlighting the value of early implantation.

Question Can neural responses measured in cochlear implant users be standardized to monitor auditory nerve health and plasticity over time?

Findings In this cohort study analyzing more than 169 000 recordings from more than 10 000 cochlear implants in 7,416 patients, auditory nerve activity varied by cochlear location and age at implantation. Children implanted at younger ages showed stronger responses and clear evidence of plasticity, particularly in the first 5 years after activation; these changes were not observed in older users.

Meaning Model-based analysis of neural recordings provide a scalable method for tracking auditory nerve health across the lifespan and highlight the importance of early implantation for long-term outcomes.

This Stroke Images case highlights the co-occurrence of ischemic strokes and uterine myoma. Go Red for Women.

ELetters should relate to an article recently published in the journal and are not a forum for providing unpublished data. Comments are reviewed for appropriate use of tone and language. Comments are not peer-reviewed. Acceptable comments are posted to the journal website only. Comments are not published in an issue and are not indexed in PubMed. Comments should be no longer than 500 words and will only be posted online. References are limited to 10. Authors of the article cited in the comment will be invited to reply, as appropriate.

Comments and feedback on AHA/ASA Scientific Statements and Guidelines should be directed to the AHA/ASA Manuscript Oversight Committee via its Correspondence page.

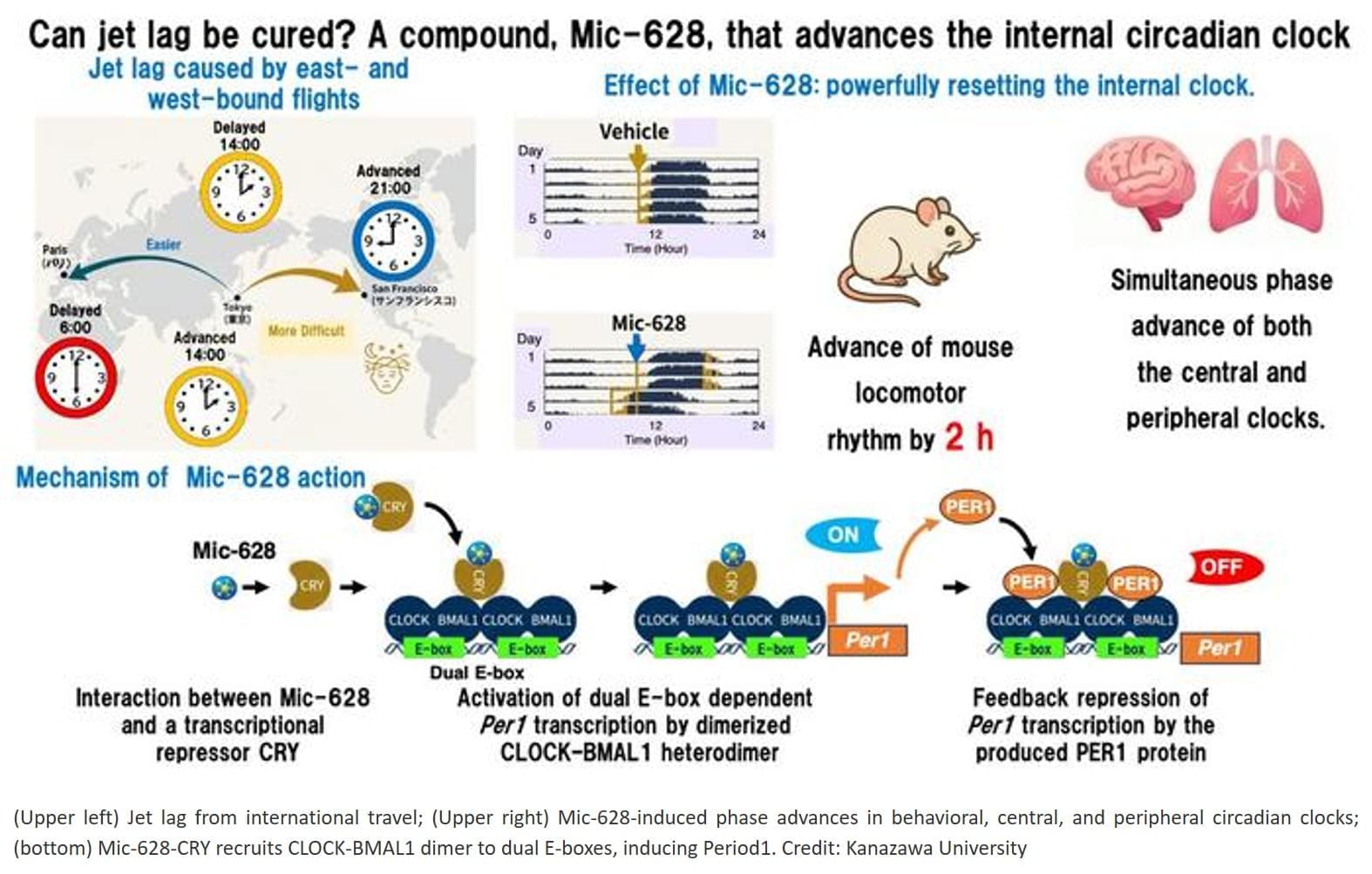

Adapting to eastward travel, such as west-to-east transmeridian flights, or to night-shift work requires advancing the internal clock, a process that normally takes longer and is physiologically harder than delaying it.

Existing methods, such as light therapy or melatonin, are heavily constrained by timing and often yield inconsistent results.

Mic-628’s consistent phase-advance effect, regardless of when it is administered, represents a new pharmacological strategy for resetting the circadian clock.

The researchers discovered that Mic-628 selectively induces the mammalian clock gene Per1.

Mic-628 works by binding to the repressor protein CRY1, promoting the formation of a CLOCK–BMAL1–CRY1–Mic-628 complex that activates Per1 transcription through a “dual E-box” DNA element.

As a result, both the central clock in the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and peripheral clocks in tissues such as the lungs were advanced—in tandem and independent of dosing time.

In a simulated jet lag mouse model (6-hour light-dark phase advance), a single oral dose of Mic-628 shortened re-entrainment time from seven days to four.

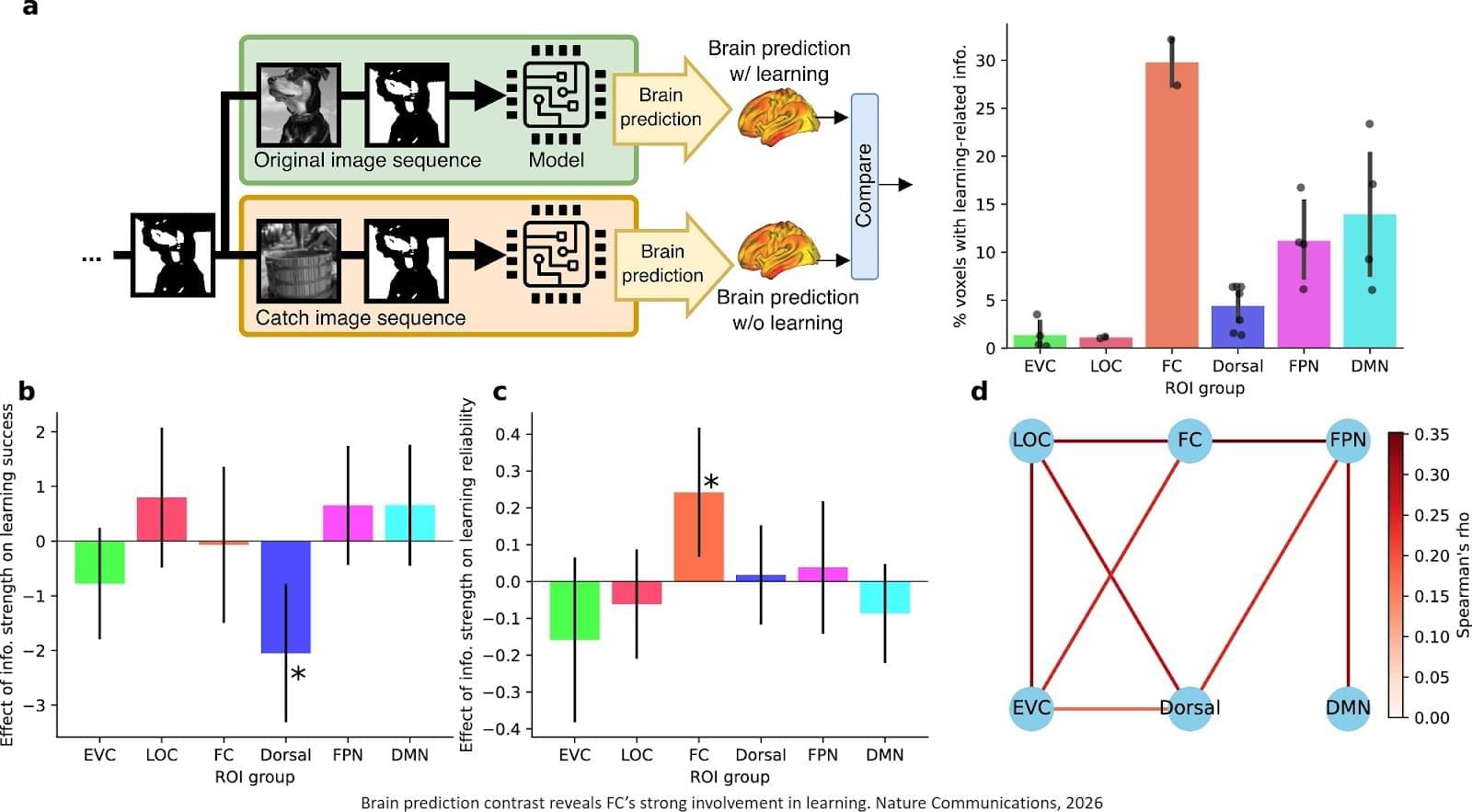

Despite decades of research, the mechanisms behind fast flashes of insight that change how a person perceives their world, termed “one-shot learning,” have remained unknown. A mysterious type of one-shot learning is perceptual learning, in which seeing something once dramatically alters our ability to recognize it again.

Now a new study, the researchers address the moments when we first recognize a blurry object, a primal ability that enabled our ancestors to avoid threats.

Published in Nature Communications, the new work pinpoints for the first time the brain region called the high-level visual cortex (HLVC) as the place where “priors” — images seen in the past and stored — are accessed to enable one-shot perceptual learning.

“Our work revealed, not just where priors are stored, but also the brain computations involved,” said co-senior study author.

Importantly, past studies had shown that patients with schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease have abnormal one-shot learning, such that previously stored priors overwhelm what a person is presently looking at to generate hallucinations.

“This study yielded a directly testable theory on how priors act up during hallucinations, and we are now investigating the related brain mechanisms in patients with neurological disorders to reveal what goes wrong,” added the author.

The research team is also looking into likely connections between the brain mechanisms behind visual perception and the better-known type of “aha moment” when we comprehend a new idea. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.

A team led by researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, has succeeded in identifying biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease in its earliest stages, before extensive brain damage has occurred. The biological processes leave measurable traces in the blood, but only for a limited period.

The discovery thus reveals a window of opportunity that could be crucial for future treatment, but also for early diagnosis via blood tests, which could begin to be tested in health care within five years.

Parkinson’s is an endemic disease with over 10 million people affected globally. As the world’s population grows older, this number is expected to more than double by 2050. At present, there is neither an effective cure nor an established screening method for detecting this chronic neurological disorder at an early stage before it has caused significant damage to the brain.

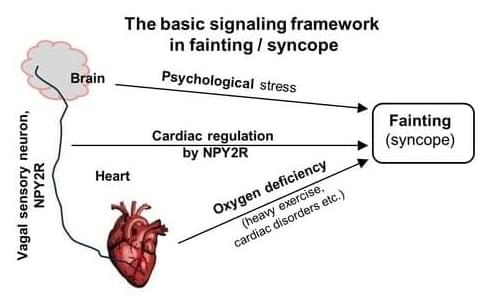

The human body is often described in parts—different limbs, systems, and organs—rather than something fully interconnected and whole. Yet many bodily processes interact in ways we may not always recognize. For example, researchers at the University of Missouri School of Medicine may have found a link between high blood pressure and an overactive nervous system.

The paper is published in the journal Cardiovascular Research.

High blood pressure, also called hypertension, is a common cardiovascular condition and a risk factor for multiple diseases and sudden health concerns like stroke or heart attack.