Summary: SuperAgers who maintain their cognitive abilities have resistance to the development of Alzheimer’s related tau tangles. The resistance to tangles may help to preserve memory.

Source: Northwestern University

While the brain tissue of modern humans are typically smooth and spherical, the study, which was published in Science on Feb 11, found that the tissue created with the ancient genes were smaller and had rough, complex surfaces.

“The question here is what makes us human,” Muotri told CNN. “Why are our brains so different from other species including our own extinct relatives?”

We all know the benefits of saunas on our mental and physical health, indeed, I recently did a video on just that, but what about the home saunas that are available so you can get the benefits as often as you desire, without having to leave the comfort of your own home, especially relevant in the current climate and recurring lockdowns… Well I have been testing both steam and infrared varieties extensively over the last year and have put together a quick guide on the pros and cons on both types. So if you have been thinking about investing yourself, or indeed you want to know which type is best for you, why not check out this video for further information. Have an awesome day…

Having already looked at the benefits of saunas, just how do home portable saunas stack up. Are they worth the expens…

Some thoughts triggered by the death of the mathematician John Conway.

Sorry for the inconvenience, ScientificAmerican.com is currently down for maintenance. Please check back later.

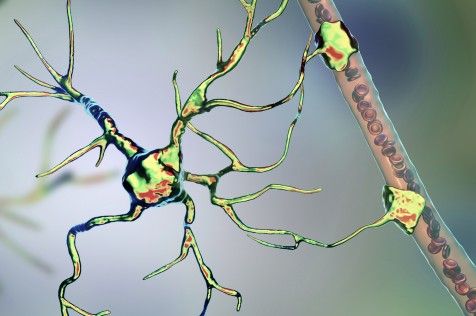

The human genome contains billions of pieces of information and around 22000 genes, but not all of it is, strictly speaking, human. Eight percent of our DNA consists of remnants of ancient viruses, and another 40 percent is made up of repetitive strings of genetic letters that is also thought to have a viral origin. Those extensive viral regions are much more than evolutionary relics: They may be deeply involved with a wide range of diseases including multiple sclerosis, hemophilia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), along with certain types of dementia and cancer.

For many years, biologists had little understanding of how that connection worked—so little that they came to refer to the viral part of our DNA as dark matter within the genome. “They just meant they didn’t know what it was or what it did,” explains Molly Gale Hammell, an associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. It became evident that the virus-related sections of the genetic code do not participate in the normal construction and regulation of the body. But in that case, how do they contribute to disease?

Eight percent of our DNA consists of remnants of ancient viruses, and another 40 percent is made up of repetitive strings of genetic letters that is also thought to have a viral origin.

For companies and governments, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The first to develop and patent 6G will be the biggest winners in what some call the next industrial revolution. Though still at least a decade away from becoming reality, 6G — which could be up to 100 times faster than the peak speed of 5G — could deliver the kind of technology that’s long been the stuff of science fiction, from real-time holograms to flying taxis and internet-connected human bodies and brains.

Most of the world is yet to experience the benefits of a 5G network, but the geopolitical race for the next big thing in telecommunications technology is already heating up. For companies and governments, the stakes couldn’t be higher.