Fusion energy has the potential to be an effective clean energy source, as its reactions generate incredibly large amounts of energy. Fusion reactors aim to reproduce on Earth what happens in the core of the sun, where very light elements merge and release energy in the process. Engineers can harness this energy to heat water and generate electricity through a steam turbine, but the path to fusion isn’t completely straightforward.

Category: nuclear energy – Page 38

Google Pivots to Nuclear Reactors to Power Its Artificial Intelligence

Google on Monday signed a deal to get electricity from small nuclear reactors to help power artificial intelligence.

The agreement to buy energy from reactors built by Kairos Power came just weeks after word that Three Mile Island, the site of America’s worst nuclear accident, will restart operations to provide energy to Microsoft.

“We believe that nuclear energy has a critical role to play in supporting our clean growth and helping to deliver on the progress of AI,” Google senior director of energy and climate said during a briefing.

Space Force funds $35M institute for versatile propulsion at U-M

This sounds very promising! The researchers are investigating the use of nuclear microreactors to power faster and more efficient electric propulsion systems.☢️🚀

To develop spacecraft that can “maneuver without regret,” the U.S. Space Force is providing $35 million to a national research team led by the University of Michigan. It will be the first to bring fast chemical rockets together with efficient electric propulsion powered by a nuclear microreactor.

The newly formed Space Power and Propulsion for Agility, Responsiveness and Resilience Institute involves eight universities, and 14 industry partners and advisers in one of the nation’s largest efforts to advance space power and propulsion, a critical need for national defense and space exploration.

Right now, most spacecraft propulsion comes in one of two flavors: chemical rockets, which provide a lot of thrust but burn through fuel quickly, or electric propulsion powered by solar panels, which is slow and cumbersome but fuel efficient. Chemical propulsion comes with the highest risk of regret, as fuel is limited. But in some situations, such as when a collision is imminent, speed may be necessary.

US Space Force backs nuclear microreactor-powered rocket breakthrough

In the future, there could be a spacecraft capable of maneuvering with unprecedented speed and agility, without the constraints of limited fuel.

The U.S. Space Force has provided funding of $35 million to create a new spacecraft that can “maneuver without regret.”

The University of Michigan is leading a team of researchers and institutions to develop this advanced spacecraft.

Unleashing Atomic Power: Record-Breaking 10.4kW Uranium Beam Reveals New Isotopes

At the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, a major advancement has been achieved with the successful acceleration of a high-power uranium beam, achieving an unprecedented 10.4 kilowatts of continuous beam power.

This achievement not only highlights the difficulty in handling uranium but underscores its importance in generating a diverse range of isotopes for scientific study. The high-power beam led to the discovery of three new isotopes within the first eight hours of its operation, marking a significant breakthrough in nuclear science and expanding our understanding of the nuclear landscape.

Breakthrough in Isotope Research.

New nuclear clean energy agreement with Kairos Power

Since pioneering the first corporate purchase agreements for renewable electricity over a decade ago, Google has played a pivotal role in accelerating clean energy solutions, including the next generation of advanced clean technologies.

Google’s first nuclear energy deal is a step toward helping the world decarbonize through investments in advanced clean energy technologies.

Google bets big on ‘mini’ nuclear reactors to feed its AI demands

“The grid needs new electricity sources to support AI technologies that are powering major scientific advances, improving services for businesses and customers, and driving national competitiveness and economic growth,” Google Senior Director for Energy and Climate Michael Terrell, said in a statement.

“This agreement helps accelerate a new technology to meet energy needs cleanly and reliably, and unlock the full potential of AI for everyone,” Terrell added.

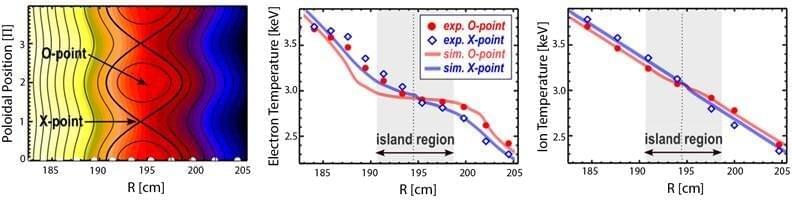

In a fusion device plasma, a steep ion temperature gradient slows the growth of magnetic islands

Future fusion power plants will require good plasma confinement to sustain reactions and generate energy. One way to contain plasma for fusion reactions is to use a tokamak, a device that applies magnetic fields to “bottle” plasma. However, magnetic islands, a type of instability in the plasma, can destroy the confining magnetic field if they grow large enough.

Fusion experiment sets record, generating 10 quadrillion watts of power

Scientists achieved a record-breaking 10 quadrillion-watt energy burst using 192 giant lasers.

Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California have achieved a groundbreaking result in nuclear fusion by generating an energy burst of more than 10 quadrillion watts. This was accomplished by using 192 giant lasers to target a tiny hydrogen pellet, releasing 1.3 megajoules of energy in a fraction of a second. The experiment, carried out at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), marks a significant step forward in fusion research and brings scientists closer to achieving “ignition,” where a fusion reaction generates more energy than it consumes.

In this latest experiment, conducted at the NIF, researchers focused intense beams of light from the world’s largest lasers onto a pea-sized pellet of hydrogen. The lasers delivered an immense amount of energy to the pellet, causing it to emit 1.3 megajoules of energy in just 100 trillionths of a second. This amount of energy is equivalent to about 10% of the sunlight that hits Earth at any moment and is significantly higher than the previous record of 170 kilojoules.

Although the hydrogen pellet absorbed more energy from the lasers than it released, the experiment produced approximately 70% of the energy absorbed, a dramatic improvement over past efforts. Scientists hope to eventually reach the break-even point, where the fusion reaction releases 100% or more of the energy it absorbs.