Article 39 Why an electron does not fall into the nucleus in terms of the strong and weak nuclear forces.

Your thoughts would be appreciated.

It can be shown one may able to derive the strong and weak nuclear forces and the internal geometry of protons and neutrons in terms of the orientation of…

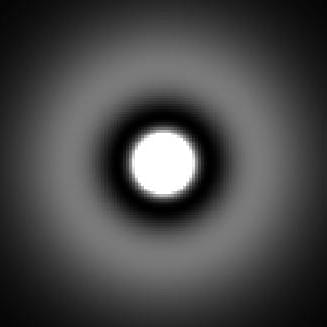

Electrons in the atom do enter the nucleus. In fact, electrons in the s states tend to peak at the nucleus. Electrons are not little balls that can fall into the nucleus under electrostatic attraction. Rather, electrons are quantized wavefunctions that spread out in space and can sometimes act like particles in limited ways. An electron in an atom spreads out according to its energy. The states with more energy are more spread out. All electron states overlap with the nucleus, so the concept of an electron “falling into” or “entering” the nucleus does not really make sense. Electrons are always partially in the nucleus.

If the question was supposed to ask, “Why don’t electrons in the atom get localized in the nucleus?” then the answer is still “they do”. Electrons can get localized in the nucleus, but it takes an interaction to make it happen. The process is known as “electron capture” and it is an important mode of radioactive decay. In electron capture, an atomic electron is absorbed by a proton in the nucleus, turning the proton into a neutron. The electron starts as a regular atomic electron, with its wavefunction spreading through the atom and overlapping with the nucleus. In time, the electron reacts with the proton via its overlapping portion, collapses to a point in the nucleus, and disappears as it becomes part of the new neutron. Because the atom now has one less proton, electron capture is a type of radioactive decay that turns one element into another element.

If the question was supposed to ask, “Why is it rare for electrons to get localized in the nucleus?” then the answer is: it takes an interaction in the nucleus to completely localize an electron there, and there is often nothing for the electron to interact with. An electron will only react with a proton in the nucleus via electron capture if there are too many protons in the nucleus. When there are too many protons, some of the outer protons are loosely bound and more free to react with the electron. But most atoms do not have too many protons, so there is nothing for the electron to interact with. As a result, each electron in a stable atom remains in its spread-out wavefunction shape. Each electron continues to flow in, out, and around the nucleus without finding anything in the nucleus to interact with that would collapse it down inside the nucleus.