Engineers discovered a new way to manage the intense heat in nuclear reactors.

Researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory used additive manufacturing to produce the first defect-free complex tungsten parts for use in extreme environments. The accomplishment could have positive implications for clean-energy technologies such as fusion energy.

Tungsten has the highest melting point of any metal, making it ideal for fusion reactors where plasma temperatures exceed 180 million degrees Fahrenheit. In comparison, the sun’s center is about 27 million degrees Fahrenheit.

In its pure form, tungsten is brittle at room temperature and easily shatters. To counter this, ORNL researchers developed an electron-beam 3D-printer to deposit tungsten, layer by layer, into precise three-dimensional shapes. This technology uses a magnetically directed stream of particles in a high-vacuum enclosure to melt and bind metal powder into a solid-metal object. The vacuum environment reduces foreign material contamination and residual stress formation.

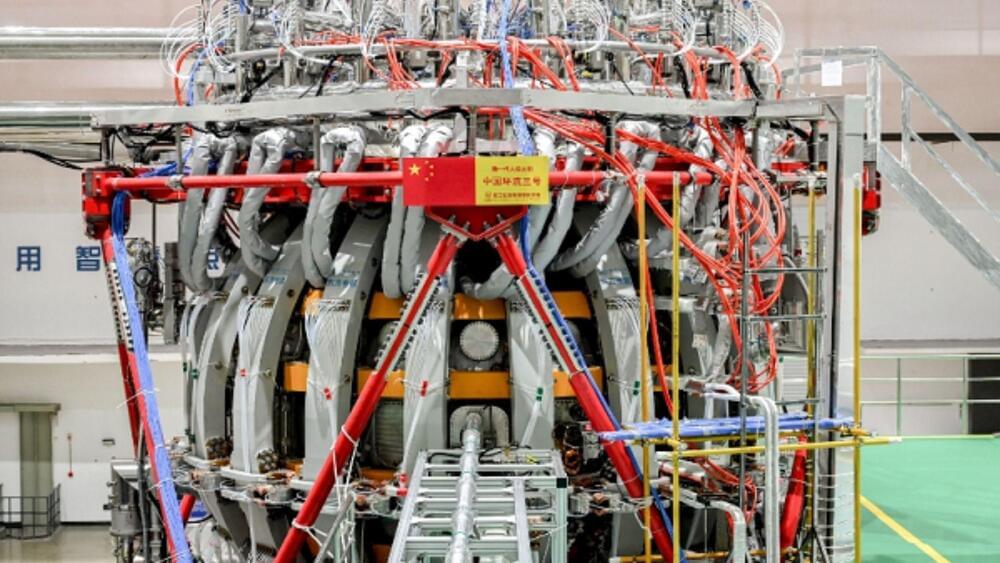

Chinese scientists have made a groundbreaking milestone in nuclear fusion. They have announced a major achievement in discovering an advanced magnetic field structure “for the first time in the world” using the Huanliu-3 (HL-3) tokamak, also known as China’s “artificial sun.”

The discovery is the result of the first round of international joint experiments conducted on the HL-3 tokamak, a project that opened to global collaboration at the end of 2023.

Four Russian warships including a nuclear submarine have reached Cuba, just 200 miles off the coast of Florida, ahead of a planned military exercise in the Atlantic. The fleet — made up of a frigate, a nuclear-powered submarine, an oil tanker and a rescue tug — arrived in Havana Bay on Wednesday, welcomed by a 21-cannon salute from Cuba. Dramatic images from the arrival show the ominous and massive vessels entering the bay as Cubans lined up on…

Bill Gates’ TerraPower broke ground yesterday on its Natrium nuclear reactor plant, making it the first advanced reactor project ever to start construction.

Once it comes online, the Natrium demonstration plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming, will be a fully functioning commercial power plant. According to Gates, founder and chairman of TerraPower, Natrium will “be the most advanced nuclear facility in the world, and it will be much safer and produce far less waste than conventional reactors.”

It’s being constructed near the retiring coal-fired Naughton power plant and is the world’s only coal-to-nuclear project under development. TerraPower, which will employ between 200 and 250 people at the Natrium facility, wants to hire the 110 former coal workers to tap into their transferrable skills.

Promethium, one of the rarest and most mysterious elements in the periodic table, has finally given up some crucial chemical secrets.

By Mark Peplow & Nature magazine

One of the rarest and most mysterious elements in the periodic table has finally given up some crucial chemical secrets, eight decades after its discovery. Researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee have become the first to use radioactive promethium to make a chemical ‘complex’ — a compound in which it is bound to a few surrounding molecules. This feat of synthesis enabled the team to study how the element bonds with other atoms in a solution with water. Published May 22 in Nature the findings fill a long-standing gap in chemistry textbooks, and could eventually lead to better methods for separating promethium from similar elements in nuclear waste, for example.

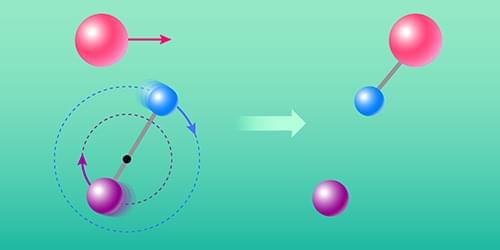

A detailed study of a reaction between a molecular ion and a neutral atom has implications for both atmospheric and interstellar chemistry.

Reactions between ions and neutral atoms or molecules occur in various settings, from planetary atmospheres to plasmas. They are also the driving force behind rich reaction chains at play in the interstellar medium (ISM)—the giant clouds of gas and dust occupying the space between stars. The ISM is cold, highly dilute, and abundant with ionizing radiation [1]. These conditions are usually unfavorable for chemistry. Yet, more than 300 molecular species have been detected in the ISM to date, of which about 80% contain carbon [2]. Now Florian Grussie at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics (MPIK) in Germany and collaborators report an experimental and theoretical study of an ion–neutral reaction: that between a neutral carbon atom and a molecular ion (HD+), made of a hydrogen and a deuterium (heavy hydrogen) atom [3, 4]. The study’s findings could improve our understanding of the chemistry of the ISM.

Ion–neutral reactions are fundamentally different from those involving only neutral species. Unlike typical neutral–neutral reactions, ion–neutral reactions often do not need to overcome an activation energy barrier and proceed efficiently even if the temperature approaches absolute zero. The reason for this difference is that, in ion–neutral reactions, the ion strongly polarizes the neutral atom or molecule, causing attractive long-range interactions that bring the reactants together.

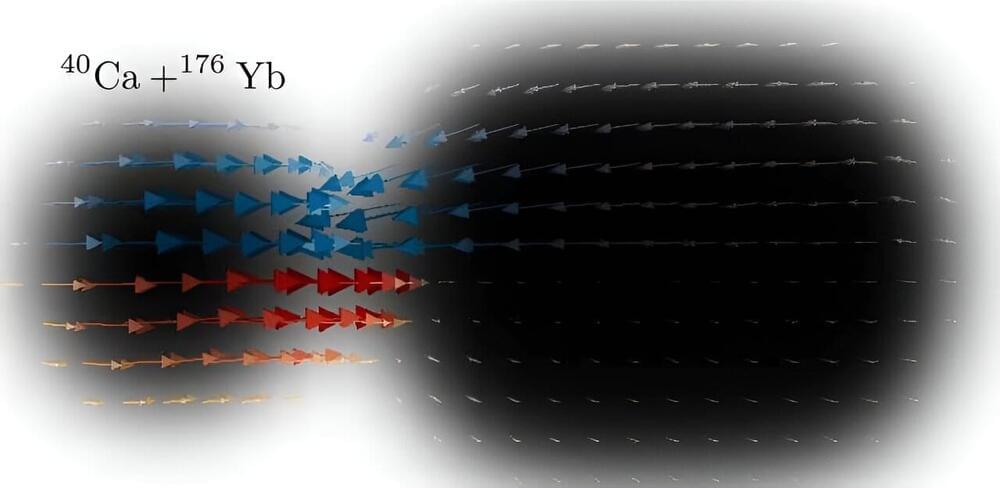

A recent study has explored the influence on low-energy fusion processes of isospin composition. This is a key nuclear property that differentiates protons from neutrons. The researchers used computational techniques and theoretical modeling to investigate the fusion of different nuclei with varying isospin configurations. The results show that the isospin composition of the nuclei in a fusion reaction plays a crucial role in understanding the reaction. The paper is published in the journal Physical Review C.

In this study, researchers at Fisk University and Vanderbilt University used high-performance computational and theoretical modeling techniques to conduct a detailed many-body method study of how the dynamics of isospin influence nuclear fusion at low energies across a series of isotopes. The study also examined how the shape of the nuclei involved affect these dynamics. In systems where the nuclei are not symmetrical, the dynamics of isospin become particularly important, often leading to a lowered fusion barrier, especially in systems rich in neutrons. This phenomenon can be explored using facilities that specialize in the generation of beams composed of exotic, unstable nuclei.

The findings provide critical knowledge regarding the fundamental nuclear processes governing these reactions, which have broad implications for fields such as nuclear physics, astrophysics, and, perhaps someday, fusion-based energy.